From observations of water masers in Seyfert galaxies it appears that the power source/central compact object is a super-massive black hole. We have discussed the possibility that this may be formed via a tidal disruption in the interstellar medium of a galaxy and that the subsequent inflow of material will continue to provide sustenance, while regulating further growth via the intermittent star-burst. The main stages in the evolution from disturbed/unstable to Seyfert galaxy are summarised in Fig. 11. This scheme is a generalised summary and the advancement to each stage is gradual i.e. many galaxies which are undergoing star-bursts will also exhibit Seyfert characteristics (Balick & Heckman 1985; Heckman et al. 1986; Rodríguez-Espinosa, Rudy & Jones 1987; Heckman et al. 1989; Fernandes & Telrevich 1995; Maiolino et al. 1995; Oliva et al. 1995; Storchi-Bergmann et al. 1996; Heckman et al. 1997) and although this ``split personality'' is not a universal occurrence, mounting evidence does support the idea that star-burst and AGN phenomena may indeed be but two facets of the same phenomenom at different evolutionary stages.

|

Figure 11. The possible evolutionary stages leading to the formation of a Seyfert galaxy. |

Focusing on the further advanced stages, in addition to the difference in orientation of the obscuring body with respect to the Earth, type 1 Seyferts appear to be in general more evolved than type 2 nuclei. This hypothesis is based on the following results:

In addition to these points, which have already been discussed:

A consequence of the evolutionary idea is that older nuclei are expected to be observable over a wider range of angles due to their depleted gas: As this gas is exhausted, the opening angle of the ionisation outflow is expected to widen, thus suggesting that Sy2s may eventually reveal their nuclei, i.e. transmute into Sy1s. This effect may be compounded since the narrow line region is partially obscured by the ~ 100 pc scale molecular ring at high inclinations, thus making Sy1s more luminous than Sy2s when observed at optical wavelengths. Unlike the previous points, however, this is a question of orientation rather than an intrinsic difference. From their conclusions that, on the whole, Sy1s contain less molecular gas Sy2s, Heckman et al. (1989) outline a scenario where, due to the still present star-burst, Sy2s will still be bright at IR and mm wavelengths. At this stage, when the central (broad line) regions are still dusty and can only be observed via scattered light, the narrow line region dominates the spectrum, although the broad line region will be visible at sufficiently low orientations. As the molecular gas is exhausted, the now un-obscured AGN reveals itself as either a Sy1 or a quasar, depending upon its original strength (Heckman et al. 1989; Deng, Xia & Wu 1997). For example, the appearance of broad lines in the Sy2 NGC 7582 between 1994 and 1998 has been noted by Aretxaga et al. (1999).

It should be noted, however, that the notion that there exists any

intrinsic differences between Seyfert classes is far

from resolved. For example,

Maiolino et al. (1997) find, from a survey of 73 galaxies, no dependence on

the amount of molecular gas with respect to Seyfert

type (53).

They do, however, speculate that

the higher star-burst activity in Sy2s is attributed to the

material in the obscuring torus still being funnelled down from the

global scale via a 100 pc-scale ring, ultimately providing the

obscuration in a Sy2 nucleus

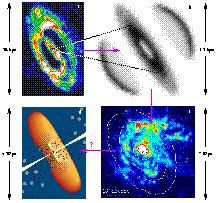

(Maiolino & Rieke 1995). This leads to the remainder of this section: In

Fig. 12 we summarise

the different scales on which fuel to the AGN is transported.

The HI gas (as observed by Jones et al. 1999) [a] is funnelled via a bar

to form a molecular ring

(54)

[b] on the sub-kiloparsec scale

(Curran et al. 1998). Within this ring an

enhanced regime of star formation (as observed in

H + [NII] by

Marconi et al. 1994) [c] occurs. From here the gas is postulated to be

transported by the small scale dusty bar (as seen in the HST/NICMOS

images of Alonso-Herrero, Maiolino & Quillen 1998, Fig. 7)

to the

sub-parsec scale of the obscuration [d] and ultimately the black hole.

+ [NII] by

Marconi et al. 1994) [c] occurs. From here the gas is postulated to be

transported by the small scale dusty bar (as seen in the HST/NICMOS

images of Alonso-Herrero, Maiolino & Quillen 1998, Fig. 7)

to the

sub-parsec scale of the obscuration [d] and ultimately the black hole.

|

Figure 12. Funnelling of the gas in

Circinus. See main text for details. It should be noted that

the molecular ring illustration [b] is a symmetrical representation of

the model of the CO emission since the distribution of material varies

between the east and west portions. In fact,

Curran (1998) estimates around 1.4 times as much gas in the NE than

the SW of the ring corresponding to the enhanced star-burst activity

towards the north [c]. HI image courtesy of Bärbel Koribalski

and H |

In summary, it is a strong possibility that the gas in (type 2) Seyferts is on all scales intimately connected (at least as far as the molecular ring, Maiolino & Rieke 1995; Schmitt et al. 1997; Curran 2000), thus being in accordance with evolutionary models of AGNs. The idea of an evolutionary difference agrees with Blandford (1990); Dopita (1998), who suggest that for AGNs in general, the accretion rate as well as the mass and angular momentum of the central engine may also have to be considered in order to provide a satisfactory scheme of unification.

(53) See Curran (2000).

Back.

(54) From interferometric observations,

Tacconi et al. (1999b) have noted several

couplings of the 100-pc scale disk to the larger scale gas in the

luminous merger NGC 6240.

Back.