Coevolution of Black Holes and Galaxies, 2003

ed. L. C. Ho (Pasadena: Carnegie Observatories,

http://www.ociw.edu/ociw/symposia/series/symposium1/proceedings.html)

| Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series, Vol. 1:

Coevolution of Black Holes and Galaxies, 2003 ed. L. C. Ho (Pasadena: Carnegie Observatories, http://www.ociw.edu/ociw/symposia/series/symposium1/proceedings.html) |

|

Abstract: Recent years have seen tremendous progress in the quest to detect supermassive black holes in the centers of nearby galaxies, and gas-dynamical measurements of the central masses of active galaxies have been valuable contributions to the local black hole census. This review summarizes measurement techniques and results from observations of spatially resolved gas disks in active galaxies, and reverberation mapping of the broad-line regions of Seyfert galaxies and quasars. Future prospects for the study of black hole masses in active galaxies, both locally and at high redshift, are discussed.

The detection of supermassive black holes in the nuclei of many nearby galaxies has been one of the most exciting discoveries in extragalactic astronomy during the past decade. Accretion onto black holes has long been understood as the best explanation for the enormous luminosities of quasars (Zel'dovich & Novikov 1964; Salpeter 1964; Rees 1984), and the luminosity generated by quasars over the history of the universe implies that most large galaxies must contain a black hole as a relic of an earlier quasar phase (Soltan 1982; Chokshi & Turner 1992; Small & Blandford 1992). While the search for evidence of black holes in nearby galaxies began 25 years ago with the seminal studies of M87 by Sargent et al. (1978) and Young et al. (1978), only a handful of galaxies were accessible to such measurements until the repair of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in 1993 made it possible to study the central dynamics of galaxies routinely at 0."1 resolution. Also within the past decade, the advent of 8 and 10-meter class ground-based telescopes has opened a new vista on our own Galactic center (see Ghez, this volume), and very long baseline interferometry observations revealed stunning dynamical evidence for a black hole in the Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 4258 (Miyoshi et al. 1995). These developments and many others have led not only to the recognition that supermassive black holes actually do exist, but to the realization that the growth of black holes must be an integral component of the galaxy formation process.

|

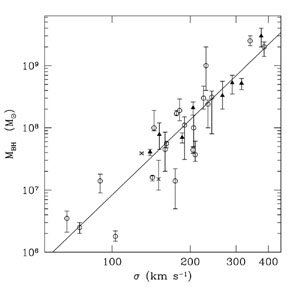

Figure 1.1. The correlation between black hole mass and stellar velocity dispersion. Triangles denote galaxies measured with HST observations of gas dynamics, crosses are H2O maser galaxies, and circles denote stellar-dynamical detections. The diagonal line is the best fit to the data as determined by Tremaine et al. (2002). |

With measurements of black hole masses in several galaxies, it became

possible for the first time to study the demographics of the black

hole population and the connection of the black holes with their host

galaxies.

Kormendy & Richstone (1995)

showed that MBH was correlated with

Lbulge, the luminosity of the spheroidal "bulge"

component of the host galaxy, albeit with substantial scatter. More

intriguing was the discovery that MBH is very tightly

correlated with

*,

the stellar velocity dispersion in the host galaxy

(Ferrarese & Merritt 2000;

Gebhardt et al. 2000a).

The scatter in this relation is surprisingly small;

Tremaine et al. (2002)

estimate the dispersion to be < 0.3 dex in log

MBH at a given value of

*,

the stellar velocity dispersion in the host galaxy

(Ferrarese & Merritt 2000;

Gebhardt et al. 2000a).

The scatter in this relation is surprisingly small;

Tremaine et al. (2002)

estimate the dispersion to be < 0.3 dex in log

MBH at a given value of

*.

This is a remarkable finding: it implies that the masses

of black holes, objects that inhabit scales of

*.

This is a remarkable finding: it implies that the masses

of black holes, objects that inhabit scales of

10-4 pc in

galaxy nuclei, are almost completely determined by the bulk

properties of their host galaxies on scales of hundreds or thousands

of parsecs. Although the MBH -

10-4 pc in

galaxy nuclei, are almost completely determined by the bulk

properties of their host galaxies on scales of hundreds or thousands

of parsecs. Although the MBH -

*

correlation is well established,

its slope, and the amount of intrinsic scatter, remain somewhat

controversial. The currently available sample of galaxies with

accurate determinations of

MBH is still modest. More measurements

of black hole masses in nearby galaxies, over the widest possible

range of host galaxy types and velocity dispersions, are needed in

order to obtain a definitive present-day black hole census.

*

correlation is well established,

its slope, and the amount of intrinsic scatter, remain somewhat

controversial. The currently available sample of galaxies with

accurate determinations of

MBH is still modest. More measurements

of black hole masses in nearby galaxies, over the widest possible

range of host galaxy types and velocity dispersions, are needed in

order to obtain a definitive present-day black hole census.

Gas-dynamical measurements of black hole masses in active galactic nuclei (AGNs) are an essential contribution to this pursuit, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. HST observations of ionized gas disks are vitally important for tracing the upper end of the black hole mass function, where stellar-dynamical measurements are hampered both by the low stellar surface brightness of the most massive elliptical galaxies and by the possibility of velocity anisotropy in nonrotating ellipticals. Maser observations have provided the most solid black hole detection outside of our own Galaxy, strengthening the case that the massive dark objects discovered in HST surveys are indeed likely to be supermassive black holes. Reverberation mapping, and secondary methods that are calibrated by comparison with the reverberation technique, offer the most promising methods to determine black hole masses at high redshift.

The topic of black holes in active galaxies is vast, and this review will only concentrate on gas-dynamical measurements of black hole masses in AGNs. Before discussing the methods and results, a few general comments are in order. As Kormendy & Richstone (1995) have pointed out, there is a potentially serious drawback to any measurement technique based on gas dynamics: unlike stars, gas can respond to nongravitational forces, and the motions of gas clouds do not always reflect the underlying gravitational potential. For all methods based on gas dynamics, it is absolutely crucial to verify that the gas is actually in gravitational orbits about the central mass. If, for example, AGN-driven outflows or other non-gravitational motions dominate, then black hole masses derived under the assumption of gravitational dynamics will be seriously compromised or completely erroneous. With that said, there are now numerous examples of ionized gas disks, and at least one maser disk, that clearly show orderly circular rotation. For reverberation mapping, the dynamical state of the broad-line emitting gas is more difficult to ascertain, but as discussed in Section 1.4 below, recent observations have provided some encouragement.

It must also be emphasized that, while these measurement techniques are capable of detecting dark mass concentrations in the centers of galaxies and determining their masses with varying degrees of accuracy, the observations do not actually prove that the dark mass is in the form of a supermassive black hole. The spatial resolution of gas-dynamical observations with HST typically corresponds to ~ 105-6 Schwarzschild radii; this is often sufficient to resolve the region over which the black hole dominates the gravitational potential of its host galaxy, but it is far from the resolution needed in order to detect relativistic motion in the strong gravitational field near the black hole's event horizon. The conclusion that the massive dark objects detected in nearby galaxies are actually black holes is supported by the two most convincing dynamical detections, in our own Galaxy and in NGC 4258; in both objects the density of the central dark mass is inferred to be so large that reasonable alternatives to a black hole can be ruled out (Maoz 1998). The best evidence for highly relativistic motion in the inner accretion disks of AGNs comes from X-ray spectra showing extremely broadened (~ 0.3c), gravitationally redshifted Fe K line emission in Seyfert nuclei (Tanaka et al. 1995; Nandra et al. 1997). While this signature has only been convincingly detected in a handful of objects, it offers a powerful confirmation of the AGN paradigm, and analysis of the relativistically broadened line profiles may even reveal evidence for the black hole's spin (e.g., Iwasawa et al. 1996).

1.2. Black Hole Masses from Dynamics of Ionized Gas

Disks

A striking discovery from the first years of HST observations was the presence of round, flattened disks of ionized gas and dust in the centers of some nearby radio galaxies (Jaffe et al. 1993; Ford et al. 1994). It was previously known from ground-based imaging that many ellipticals contained nuclear patches of dust (Kotanyi & Ekers 1979; Sadler & Gerhard 1985), but HST revealed that the dust was often arranged in well-defined disks too small to be resolved from the ground. Imaging surveys with HST have found such disks, with typical radii of 100 - 1000 pc, in ~ 20% of giant elliptical galaxies (e.g., Verdoes Kleijn et al. 1999; de Koff et al. 2000; Tran et al. 2001).

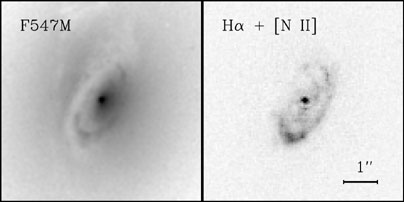

Jaffe et al. (1999) show that nuclear gas disks in early-type galaxies fall into two general categories. The most common type are dusty disks, which are easily detected by their obscuration in broad-band optical HST images. In radio galaxies with flattened dust disks, the radio axis is usually nearly perpendicular to the disk plane (de Koff et al. 2000). The dust is usually accompanied by an ionized component. Figure 1.2 shows an example, the disk in the S0 galaxy NGC 3245. The second class consists of ionized gas disks without associated dust. M87 (Ford et al. 1994) is the prototype of this category. Ionized disks are sometimes found to have filamentary or spiral structure.

|

Figure 1.2. An example of a dusty

emission-line disk: HST images of the

S0 galaxy NGC 3245. The left panel is a continuum image taken with

the HST F547M filter (equivalent to the V band), and the

right panel shows a continuum-subtracted, narrow-band image isolating the

H |

Soon after the first HST servicing mission, the first spectroscopic

investigations of the kinematics of these disks were performed with

the Faint Object Spectrograph (FOS). The first target was M87, for

which Harms et al. (1994)

detected a steep velocity gradient across

the nucleus in the H ,

[N II], and [O III] emission

lines, consistent with Keplerian rotation in an inclined disk. The

central mass was found to be (2.4 × 0.7) × 109

M

,

[N II], and [O III] emission

lines, consistent with Keplerian rotation in an inclined disk. The

central mass was found to be (2.4 × 0.7) × 109

M ,

remarkably close to the values first determined by

Young et al. (1978)

and Sargent et al. (1978).

The second gas-dynamical study with HST found a central dark mass

of (4.9 × 1.0) × 108

M

,

remarkably close to the values first determined by

Young et al. (1978)

and Sargent et al. (1978).

The second gas-dynamical study with HST found a central dark mass

of (4.9 × 1.0) × 108

M in the

radio galaxy NGC 4261

(Ferrarese, Ford, & Jaffe 1996).

These dramatic results opened a new chapter in the search for supermassive

black holes, demonstrating that spatially resolved gas disks could

indeed be used to measure the central masses of galaxies. In contrast

to stellar dynamics, the gas-dynamical method is extremely appealing

in its simplicity. Modeling the kinematics of a thin, rotating disk

is conceptually straightforward. Furthermore, observations of

emission-line velocity fields require less telescope time than

absorption-line spectroscopy.

in the

radio galaxy NGC 4261

(Ferrarese, Ford, & Jaffe 1996).

These dramatic results opened a new chapter in the search for supermassive

black holes, demonstrating that spatially resolved gas disks could

indeed be used to measure the central masses of galaxies. In contrast

to stellar dynamics, the gas-dynamical method is extremely appealing

in its simplicity. Modeling the kinematics of a thin, rotating disk

is conceptually straightforward. Furthermore, observations of

emission-line velocity fields require less telescope time than

absorption-line spectroscopy.

After these initial detections, progress was made on two fronts. The installation of the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS), a long-slit instrument, greatly expanded the capabilities of HST for dynamical measurements, making it possible to perform surveys of large numbers of galaxies. In addition, the development of techniques to model the kinematic data in detail led to more robust measurements. At the center of a disk, the large spatial gradients in rotation velocity and emission-line surface brightness are smeared out by the telescope point-spread function (PSF) and by the nonzero size of the spectroscopic aperture. Macchetto et al. (1997) were the first to model the effects of instrumental blurring on HST gas-kinematic data, in their analysis of long-slit spectra of the M87 disk, and detailed descriptions of modeling techniques have been given by Barth et al. (2001), Maciejewski & Binney (2001), and Marconi et al. (2003).

The feasibility of performing a black hole detection in any given

galaxy can be roughly quantified in terms of

rG, the radius of the

"sphere of influence" over which the black hole dominates the

gravitational potential of its host galaxy. This quantity is given by

rG = G M

Detection of black holes via their influence on the motions of stars

or gas is most readily accomplished when observations are able to

probe spatial scales smaller than

rG, but it should be borne in mind

that this is at best an approximate criterion. The stellar velocity

dispersion is an aperture-dependent quantity, so there is no uniquely

determined value of rG for a given galaxy. Even when

rG is

unresolved the black hole will still influence the motions of stars

and gas at larger radii. In stellar-dynamical measurements, it is

possible to obtain information from spatial scales smaller than the

instrumental resolution by measuring higher-order moments of the

central line-of-sight velocity profile, since extended wings on the

velocity profile are the signature of high-velocity stars orbiting

close to the black hole (e.g.,

van der Marel 1994).

This technique

cannot generally be applied to gas-dynamical measurements, however,

because it would require knowledge of the emissivity profile of the

gas on spatial scales smaller than the instrumental resolution.

The analysis of a gas-dynamical dataset consists of the following

basic steps. The galaxy's stellar light profile must be measured,

corrected for dust absorption if necessary, and converted to a

three-dimensional luminosity density. A model velocity field is

computed for the combined potential of the black hole and the galaxy

mass distribution, usually assuming a spatially constant stellar

mass-to-light ratio. After projecting the velocity field to a given

distance and inclination angle, the model is synthetically

"observed" by simulating the passage of light through the

spectrograph optics and measuring the resulting model line profiles.

Finally, the model fit to the measured emission-line velocity field is

optimized to obtain the best-fitting value of

MBH. In addition to MBH, the free

parameters in the kinematic model fit include the disk

inclination and major axis position angle, and the stellar

mass-to-light ratio; these can be determined from the kinematic data

if observations are obtained at three or more parallel positions of

the spectrograph slit. With up-to-date analysis techniques and

high-quality STIS data, it is possible to achieve formal measurement

uncertainties on MBH of order ~ 25% or better for

galaxies with well-behaved disks (e.g.,

Barth et al. 2001).

This makes the gas-dynamical method very competitive with the precision

that can be achieved by stellar-dynamical measurements.

Figure 1.3 illustrates model calculations for the

projected radial velocities along the major axis of an inclined gas

disk. The models have been calculated for a disk inclined at

60° to the line of sight, in a galaxy at a distance of 20 Mpc

with MBH = 0, 107, 108, and

109

M

The middle ground between these two extremes is illustrated by the

108

M

Since the gas can respond to non-gravitational forces, it is essential

for the observations to map the disk structure in sufficient detail

that the assumption of gravitational motion can be tested. This is a

nontrivial concern, as there are examples of galaxies in which the gas

does not rotate at the circular velocity (e.g.,

Fillmore, Boroson, & Dressler 1986;

Kormendy & Westpfahl 1989).

The case of IC 1459 serves

as a cautionary tale. FOS observations at 6 positions within 0."3

of the nucleus revealed a steep central velocity gradient in the

ionized gas, and disk model fits implied the presence of a central

dark mass of (1 - 4) × 108

M

Most of the nuclear disks observed spectroscopically with HST have

revealed evidence for substantial internal velocity dispersions, even

when the velocity field is clearly dominated by rotation. That is,

the gas disks are not in purely quiescent circular rotation, and the

disks have some degree of internal velocity structure or turbulence.

The intrinsic emission-line velocity dispersion

The origin of this internal velocity dispersion is unknown, and the

interpretation of

Since different groups have used a variety of methods to treat this

problem in dynamical analyses (sometimes ignoring it altogether), and

since

Most gas-dynamical studies to date have concentrated on elliptical and

S0 galaxies, but STIS data have now been obtained for dozens of spiral

galaxies as well (e.g.,

Marconi et al. 2003).

In principle, the

gas-dynamical method can work equally well for spirals, but there are

some additional complications. One is the presence of nuclear star

clusters, which are nearly ubiquitous in late-type spirals

(Carollo, Stiavelli, & Mack 1998;

Böker et al. 2002).

The nuclear star clusters are typically young

(Walcher et al. 2003),

and the dynamical

modeling must take into account the possible radial gradient in M

/ L.

Another caveat is that spiral arms or bar structure can lead to

departures from circular rotation in the ionized gas

(Koda & Wada 2002;

Maciejewski 2003).

Only ~ 10 - 20% of spirals appear to have

orderly emission-line velocity fields suitable for disk-model fitting

to derive MBH

(Sarzi et al. 2001),

so some care is needed when

selecting targets for HST gas-dynamical surveys.

Ho et al. (2002)

have shown that orderly rotation in the emission-line gas almost

exclusively occurs in galaxies having orderly, symmetric circumnuclear

dust-lane morphology that can be detected in HST imaging data, and

this offers a promising way to maximize the rate of successful

MBH measurements in future programs.

Even when gas-dynamical data cannot provide a direct measurement of

black hole mass, either due to insufficient resolution or irregular

kinematics, they can still be used to derive upper limits to

MBH from the central amplitude of the rotation curve

or the central emission-line width. For galaxies with

Gas-dynamical measurements using HST data have now been published

for about a dozen galaxies

(Harms et al. 1994;

Ferrarese et al. 1996;

Macchetto et al. 1997;

van der Marel & van den Bosch 1998;

Bower et al. 1998;

Ferrarese & Ford 1999;

Sarzi et al. 2001;

Barth et al. 2001;

Verdoes Kleijn et al. 2002;

Marconi et al. 2003).

The results,

together with stellar-dynamical measurements, have been compiled by

Kormendy & Gebhardt (2001),

Merritt & Ferrarese (2001), and

Tremaine et al. (2002).

This number will continue to increase over the next

several years, since STIS gas-kinematic observations have been

obtained or scheduled for over 100 galaxies. However, it remains to

be seen how many of these datasets will lead to accurate measurements

of black hole masses. A substantial fraction of the galaxies will

probably not have well-behaved gas disks suitable for modeling, and in

many of the target galaxies rG may be much smaller

than the resolution limit of HST

(Merritt & Ferrarese 2001).

Thus, it remains worthwhile to search for additional nearby galaxies having

morphologically regular disks that will make promising targets for

future spectroscopic observations.

With the small projected sizes of

rG in most nearby galaxies,

ground-based observations cannot generally be used to perform

gas-dynamical measurements of

MBH. One exception is the nearby (D = 3.5 Mpc)

radio galaxy Cen A.

Marconi et al. (2001)

obtained near-infrared spectra of this galaxy in 0."5 seeing, and

measured the velocity field of the

Pa

Water vapor maser emission at

A detailed review of the properties of the NGC 4258 maser system and a

listing of other known H2O maser galaxies is given by

Moran, Greenhill, & Herrnstein (1999).

Hundreds of galaxies have been surveyed for H2O masers (e.g.,

Braatz, Wilson, & Henkel 1996;

Greenhill et al. 2002,

2003),

and there are about 30 known sources to date.

Braatz et al. (1997)

find that powerful H2O masers are only

detected in Seyfert 2 and LINER nuclei, and not in Seyfert 1 galaxies.

This is consistent with the geometrical picture of AGN unification

models, which posit the existence of an edge-on torus or disk in the

type 2 objects. The large path length along our line of sight in an

edge-on disk permits maser amplification, while a more face-on disk in

a Type 1 AGN would not emit maser lines in our direction. Further

confirmation of this geometric structure comes from detection of large

X-ray obscuring columns (e.g.,

Makishima et al. 1994;

Iwasawa, Maloney, & Fabian 2002)

and polarized emission lines from obscured nuclei (e.g.,

Antonucci & Miller 1985;

Wilkes et al. 1995)

in some H2O maser galaxies.

Disklike structures have been detected in several other maser

galaxies, but NGC 4258 remains the only one for which the central mass

has been derived with high precision. The maser clouds in NGC 1068

appear to trace the surface of a geometrically thick torus rather than

a thin disk and their velocities fall below a Keplerian curve,

suggesting a central mass of ~ 107

M

Reverberation mapping uses temporal variability of active nuclei to

probe the size and structure of the broad-line region (BLR) of Seyfert

1 nuclei and quasars. The basic principle is that variability in the

ionizing photon output of the central engine will be followed by

corresponding variations in the emission-line luminosity, after a time

delay dependent on the light-travel time between the ionizing source

and the emission-line clouds

(Blandford & McKee 1982).

By monitoring

the continuum and emission-line brightness of a broad-lined AGN over a

sufficient time period, the lag between continuum variations and

emission-line response can be derived, giving a size scale for the

region emitting the line; typical sizes range from a few light-days up

to ~ 1 light-year. Thus, the method makes use of the time domain

to resolve structures that cannot be resolved spatially, and the

measurement accuracy depends on temporal sampling rather than spatial

resolution. The literature on reverberation mapping is extensive, and

this brief summary will concentrate on just a few recent results. A

thorough review of the observational and analysis techniques used in

reverberation-mapping campaigns is given by

Peterson (2001).

If the motions in the BLR are dominated by gravity (rather than, for

example, radiatively-driven outflows), then the central mass can be

derived from the BLR radius combined with a characteristic velocity.

Essentially, the black hole mass is derived as

MBH = f v2 r / G, where

v is some measure of the broad-line velocity width (typically the

full width at half maximum), r is the BLR radius derived from the

measured time delay, and f is an order-unity factor that depends on

the geometry of the BLR (i.e., disklike or spherical). Reverberation

masses for 34 Seyfert 1 galaxies and low-redshift quasars have been

determined by

Wandel, Peterson & Malkan (1999)

and Kaspi et al. (2000).

The method is subject to some potentially serious systematic

errors, however, as emphasized by

Krolik (2001);

the unknown geometry

and emissivity distribution of the BLR clouds can lead to biases in

the derived masses, and it is critically important to verify that the

BLR velocity field is in fact dominated by gravitational motion.

Recent observations have yielded some encouraging results. Since the

BLR is radially stratified in ionization level, highly ionized clouds

emitting He IIand C IV respond most quickly to continuum

variations, with response times of a few days, while lines such as

H

Another key question is whether reverberation mapping yields black

hole masses that are consistent with the host galaxy properties of the

AGNs. Gebhardt et al. (2000b)

and Ferrarese et al. (2001)

demonstrated that the reverberation masses and velocity dispersions of

several Seyfert nuclei are in good agreement with the

MBH -

Overall, the agreement between the

MBH -

Reverberation mapping can be extended to higher redshifts, since it is

not dependent on spatial resolution, but the longer variability

timescales for higher-mass black holes in luminous quasars, combined

with cosmological time dilation, can require monitoring campaigns with

durations that are a significant fraction of an individual

astronomer's career!

Kaspi et al. (2003)

present preliminary results

from an ongoing, eight-year campaign to monitor 11 luminous quasars at

2.1 < z < 3.2. Continuum variations have been detected, but the

corresponding emission-line variability has not yet been seen.

Reverberation observations of quasars are a fundamental

probe of black hole masses at high redshift, and efforts to monitor

additional quasars over a wide redshift range should be encouraged,

despite the long timescales involved.

One important result of the reverberation campaigns has been the

detection of an empirical correlation between the BLR radius and the

optical continuum luminosity, usually measured at 5100 Å

(Wandel, Malkan, & Peterson 1999;

Kaspi et al. 2000).

With a sample of 34 reverberation-mapped AGNs,

Kaspi et al. (2000)

find rBLR

These secondary methods are extremely valuable since they offer the

most straightforward estimates of black hole masses at high redshift,

although there are potential biases that must be kept in mind. The

derived BLR size and

MBH depend on the observed continuum

luminosity, but this can be affected by dust extinction

(Baker & Hunstead 1995),

or by relativistic beaming of synchrotron emission in radio-loud objects

(Whiting, Webster, & Francis 2001).

If the BLR

has a flattened, disklike geometry, then the effects of source

orientation on the observed linewidth must be accounted for (e.g.,

McLure & Dunlop 2002).

An additional concern is that the rBLR-L

relation has only been calibrated against the Kaspi et al. reverberation

sample, which covers a somewhat limited range both in

black hole mass (MBH

I conclude with a very incomplete list of a few important and

tractable problems that can be addressed in the foreseeable future by

new observations.

1. More dynamical measurements of black hole masses in nearby galaxies

are needed, over the widest possible range of host galaxy masses

and velocity dispersions, so that the slope of the

MBH -

2. Direct comparisons of stellar and gas-dynamical measurements for

the same galaxies are a needed consistency check that should be

performed for galaxies over a wide range in

3. What causes the intrinsic velocity dispersion observed in nuclear

gas disks? Is it possible to determine central masses

accurately for disks having

4. What can we learn about black hole demographics from AGNs at the

extremes of the Hubble sequence? The broad-line widths and

continuum luminosities of high-redshift quasars imply masses of up

to ~ 1010

M

5. How do the

MBH -

*2.

Projected onto the sky, and scaled to

typical parameters for an HST measurement, this corresponds to

*2.

Projected onto the sky, and scaled to

typical parameters for an HST measurement, this corresponds to

(1)

.

To demonstrate the effects of varying

MBH, the same stellar mass profile has been used

for all four models. The model velocity fields have been convolved

with the STIS PSF and sampled over an aperture corresponding to an

0."1-wide slit, and the curves represent the mean velocity that

would be observed as a function of position along the slit. At one

extreme, the sphere of influence of the 107

M

.

To demonstrate the effects of varying

MBH, the same stellar mass profile has been used

for all four models. The model velocity fields have been convolved

with the STIS PSF and sampled over an aperture corresponding to an

0."1-wide slit, and the curves represent the mean velocity that

would be observed as a function of position along the slit. At one

extreme, the sphere of influence of the 107

M black hole is unresolved, and the 107

M

black hole is unresolved, and the 107

M model is barely distinguishable from

the model with no black hole. The unresolved Keplerian emission can

still be observed in the form of high-velocity wings on the central

line profile, but this is of little use in determining

MBH. The opposite extreme is the 109

M

model is barely distinguishable from

the model with no black hole. The unresolved Keplerian emission can

still be observed in the form of high-velocity wings on the central

line profile, but this is of little use in determining

MBH. The opposite extreme is the 109

M black hole, for which the

Keplerian region is extremely well resolved and the black hole would

be readily detected. Instrumental blurring causes a turnover in the

velocity curves at about 0."15 in this case, and Keplerian

rotation can only be clearly detected at larger radii. Thus,

Keplerian rotation can only be verified in detail (in the sense of

having several independent data points to trace the

v

black hole, for which the

Keplerian region is extremely well resolved and the black hole would

be readily detected. Instrumental blurring causes a turnover in the

velocity curves at about 0."15 in this case, and Keplerian

rotation can only be clearly detected at larger radii. Thus,

Keplerian rotation can only be verified in detail (in the sense of

having several independent data points to trace the

v  r-1/2 dependence) for galaxies with exceptionally

well-resolved rG. To date, the only published

HST gas-dynamical measurements

that have unambiguously detected the Keplerian region are those of M87

(Macchetto et al. 1997)

and M84

(Bower et al. 1998).

r-1/2 dependence) for galaxies with exceptionally

well-resolved rG. To date, the only published

HST gas-dynamical measurements

that have unambiguously detected the Keplerian region are those of M87

(Macchetto et al. 1997)

and M84

(Bower et al. 1998).

black hole in Figure 1.3. In this case, the

Keplerian rise in velocity is not detected; instead, a steep but

smooth velocity gradient across the nucleus is observed. The mass of

the black hole can still be determined from the steepness of this

central gradient, provided that the observations give sufficient

information to distinguish the velocity curves from those of the

MBH = 0

case. It is possible in principle to measure MBH even in

galaxies for which

rG is formally unresolved, if it can be shown

that the disk has an excess rotation velocity relative to the

best-fitting model without a black hole. However, in such cases there

are practical complications that may limit the measurement accuracy:

it is critical to determine the stellar luminosity density profile and

mass-to-light ratio accurately, and spatial gradients in M /

L are an

added complication. In general, the most confident detections of

black holes will be in those relatively rare objects for which the

Keplerian region can be clearly traced, but the majority of

gas-dynamical mass measurements will come from objects for which the

mass is determined primarily from the steepness of the central

velocity gradient rather than from fitting models to a well-resolved

Keplerian velocity field.

black hole in Figure 1.3. In this case, the

Keplerian rise in velocity is not detected; instead, a steep but

smooth velocity gradient across the nucleus is observed. The mass of

the black hole can still be determined from the steepness of this

central gradient, provided that the observations give sufficient

information to distinguish the velocity curves from those of the

MBH = 0

case. It is possible in principle to measure MBH even in

galaxies for which

rG is formally unresolved, if it can be shown

that the disk has an excess rotation velocity relative to the

best-fitting model without a black hole. However, in such cases there

are practical complications that may limit the measurement accuracy:

it is critical to determine the stellar luminosity density profile and

mass-to-light ratio accurately, and spatial gradients in M /

L are an

added complication. In general, the most confident detections of

black holes will be in those relatively rare objects for which the

Keplerian region can be clearly traced, but the majority of

gas-dynamical mass measurements will come from objects for which the

mass is determined primarily from the steepness of the central

velocity gradient rather than from fitting models to a well-resolved

Keplerian velocity field.

(Verdoes Kleijn et al. 2000).

More recently, STIS observations have mapped out the circumnuclear

kinematics in much greater detail and found an irregular and

asymmetric velocity field that cannot be interpreted in terms of flat

disk models; a stellar-dynamical analysis finds

MBH = (2.6 ± 1) × 109

M

(Verdoes Kleijn et al. 2000).

More recently, STIS observations have mapped out the circumnuclear

kinematics in much greater detail and found an irregular and

asymmetric velocity field that cannot be interpreted in terms of flat

disk models; a stellar-dynamical analysis finds

MBH = (2.6 ± 1) × 109

M (Cappellari et al. 2002).

Thus, the ionized gas fails to be a useful probe of the gravitational

potential in this galaxy.

(Cappellari et al. 2002).

Thus, the ionized gas fails to be a useful probe of the gravitational

potential in this galaxy.

gas tends

to be greatest at the nucleus, and observed values span a wide range,

exceeding 500 km s-1 in extreme cases (e.g.,

van der Marel & van den Bosch 1998).

gas tends

to be greatest at the nucleus, and observed values span a wide range,

exceeding 500 km s-1 in extreme cases (e.g.,

van der Marel & van den Bosch 1998).

gas

remains the single most important unresolved

problem for gas-dynamical measurements of black hole masses. In a

study of the radio galaxy NGC 7052,

van der Marel & van den Bosch (1998)

argued that

gas

remains the single most important unresolved

problem for gas-dynamical measurements of black hole masses. In a

study of the radio galaxy NGC 7052,

van der Marel & van den Bosch (1998)

argued that

gas was

due to local turbulence in gas that

remained in bulk motion on circular orbits at the local circular

velocity. Another possibility that has been considered is that the

disks are composed of a large number of clouds with small filling

factor, and that the individual clouds are on noncircular orbits that

are nevertheless dominated by gravity (e.g.,

Verdoes Kleijn et al. 2000).

This is analogous to the effect of "asymmetric drift" that

is well-known in stellar dynamics (e.g.,

Binney & Tremaine 1987).

In this situation, the gas disk would be supported against gravity by

both rotation and random motions, and models based on pure circular

rotation would underestimate the true black hole masses. The

asymmetric drift correction to MBH is expected to be

small when

(

gas was

due to local turbulence in gas that

remained in bulk motion on circular orbits at the local circular

velocity. Another possibility that has been considered is that the

disks are composed of a large number of clouds with small filling

factor, and that the individual clouds are on noncircular orbits that

are nevertheless dominated by gravity (e.g.,

Verdoes Kleijn et al. 2000).

This is analogous to the effect of "asymmetric drift" that

is well-known in stellar dynamics (e.g.,

Binney & Tremaine 1987).

In this situation, the gas disk would be supported against gravity by

both rotation and random motions, and models based on pure circular

rotation would underestimate the true black hole masses. The

asymmetric drift correction to MBH is expected to be

small when

( gas /

vrot)2 << 1, but this must be tested on a

case by case basis by computing models for the emission-line widths.

Various approaches to calculating the asymmetric drift in gas disks

have been presented by

Cretton, Rix, & de Zeeuw (2000),

Verdoes Kleijn et al. (2000,

2002),

and Barth et al. (2001).

gas /

vrot)2 << 1, but this must be tested on a

case by case basis by computing models for the emission-line widths.

Various approaches to calculating the asymmetric drift in gas disks

have been presented by

Cretton, Rix, & de Zeeuw (2000),

Verdoes Kleijn et al. (2000,

2002),

and Barth et al. (2001).

gas varies

widely among different galaxies, the influence of

the intrinsic velocity dispersion could be responsible for some of the

apparent scatter in the MBH -

gas varies

widely among different galaxies, the influence of

the intrinsic velocity dispersion could be responsible for some of the

apparent scatter in the MBH -

*

relation. Now that large samples of

galaxies have been observed with STIS, it may be possible to discern

whether there are any correlations of

*

relation. Now that large samples of

galaxies have been observed with STIS, it may be possible to discern

whether there are any correlations of

gas with

the level of nuclear

activity or with the Hubble type or any other property of the host

galaxy; detection of any clear trends might help to elucidate the

origin of the intrinsic dispersion. Three-dimensional

hydrodynamical simulations have evolved to the point where it is now

becoming feasible to model the turbulent structure of gas disks in

galaxies (e.g.,

Wada, Meurer, & Norman 2002);

this work may lead to new insights on how best to interpret

gas with

the level of nuclear

activity or with the Hubble type or any other property of the host

galaxy; detection of any clear trends might help to elucidate the

origin of the intrinsic dispersion. Three-dimensional

hydrodynamical simulations have evolved to the point where it is now

becoming feasible to model the turbulent structure of gas disks in

galaxies (e.g.,

Wada, Meurer, & Norman 2002);

this work may lead to new insights on how best to interpret

gas in

gas-dynamical

measurements. Further discussion of the intrinsic velocity dispersion

problem is presented by

Verdoes Kleijn et al. (2003).

gas in

gas-dynamical

measurements. Further discussion of the intrinsic velocity dispersion

problem is presented by

Verdoes Kleijn et al. (2003).

*

*

100

km s-1, where direct measurements of

MBH are scarce, upper limits are

valuable additions to the black hole census. For example, from a

large sample of ground-based rotation curves,

Salucci et al. (2000)

demonstrated that late-type spirals must generally have

MBH

100

km s-1, where direct measurements of

MBH are scarce, upper limits are

valuable additions to the black hole census. For example, from a

large sample of ground-based rotation curves,

Salucci et al. (2000)

demonstrated that late-type spirals must generally have

MBH

106-7

M

106-7

M .

Sarzi et al. (2002)

measured upper limits to MBH from the central

emission-line widths observed in STIS spectra of 16 galaxies having

.

Sarzi et al. (2002)

measured upper limits to MBH from the central

emission-line widths observed in STIS spectra of 16 galaxies having

*

between 80 and 270 km s-1. The derived

upper limits are consistent with the

MBH -

*

between 80 and 270 km s-1. The derived

upper limits are consistent with the

MBH -

*

relation, further

confirming that few galaxies (perhaps none) are strong outliers with

very overmassive black holes relative to their bulge luminosity or

velocity dispersion.

*

relation, further

confirming that few galaxies (perhaps none) are strong outliers with

very overmassive black holes relative to their bulge luminosity or

velocity dispersion.

and

[Fe II] emission lines.

They detected a steep central velocity gradient with a turnover to

Keplerian rotation outside the region dominated by atmospheric seeing,

and derived a central dark mass of

2+3.0-1.4 × 108

M

and

[Fe II] emission lines.

They detected a steep central velocity gradient with a turnover to

Keplerian rotation outside the region dominated by atmospheric seeing,

and derived a central dark mass of

2+3.0-1.4 × 108

M .

Although the black hole mass was not determined with very high

precision, this measurement serves as a proof of concept

that ground-based observations of near-infrared emission lines can be

used for gas-dynamical analysis. In the future, near-infrared

integral-field spectrographs, coupled with laser-guided adaptive

optics on 8-10m or larger telescopes, will make it possible to pursue

such measurements from the ground routinely, at spatial resolution

comparable to that of HST in the optical. Also, the Atacama

Large Millimeter Array will provide new high-resolution

views of circumnuclear disks and new probes of disk dynamics with

molecular emission lines.

.

Although the black hole mass was not determined with very high

precision, this measurement serves as a proof of concept

that ground-based observations of near-infrared emission lines can be

used for gas-dynamical analysis. In the future, near-infrared

integral-field spectrographs, coupled with laser-guided adaptive

optics on 8-10m or larger telescopes, will make it possible to pursue

such measurements from the ground routinely, at spatial resolution

comparable to that of HST in the optical. Also, the Atacama

Large Millimeter Array will provide new high-resolution

views of circumnuclear disks and new probes of disk dynamics with

molecular emission lines.

1.3. Black Hole Masses from Observations of

H2O Masers

= 1.35 cm from the

nucleus of the low-luminosity Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 4258 was detected by

Claussen, Heiligman, & Lo (1984).

The maser emission consists of a bright core

with several distinct components near the systemic velocity arranged

in an elongated region

(Greenhill et al. 1995),

as well as "satellite" lines separated by

± 800 - 1000 km s-1 from the systemic features

(Nakai, Inoue, & Miyoshi 1993).

The presence of high-velocity emission was suggestive of a disk rotating

about a central mass of ~ 107

M

= 1.35 cm from the

nucleus of the low-luminosity Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 4258 was detected by

Claussen, Heiligman, & Lo (1984).

The maser emission consists of a bright core

with several distinct components near the systemic velocity arranged

in an elongated region

(Greenhill et al. 1995),

as well as "satellite" lines separated by

± 800 - 1000 km s-1 from the systemic features

(Nakai, Inoue, & Miyoshi 1993).

The presence of high-velocity emission was suggestive of a disk rotating

about a central mass of ~ 107

M (Watson & Wallin 1994),

and the breakthrough observation came when

Miyoshi et al. (1995)

used the Very

Long Baseline Array to map out the positions of the high-velocity

features. They found that the satellite masers traced out a

near-perfect Keplerian velocity curve on either side of the nucleus,

allowing a precise determination of the enclosed mass within the inner

radius of the disk (3.9 milliarcsec, corresponding to a radius of only

0.14 pc). For a distance of 7.2 Mpc, the central mass is found to be

3.9 × 107

M

(Watson & Wallin 1994),

and the breakthrough observation came when

Miyoshi et al. (1995)

used the Very

Long Baseline Array to map out the positions of the high-velocity

features. They found that the satellite masers traced out a

near-perfect Keplerian velocity curve on either side of the nucleus,

allowing a precise determination of the enclosed mass within the inner

radius of the disk (3.9 milliarcsec, corresponding to a radius of only

0.14 pc). For a distance of 7.2 Mpc, the central mass is found to be

3.9 × 107

M . It

is very unlikely that this mass could be

composed of a cluster of dark objects such as stellar remnants or

brown dwarfs, since the cluster density would be so large that its

lifetime against evaporation or collisions would be short compared to

the age of the galaxy

(Maoz 1995,

1998).

This makes NGC 4258 the most

compelling dynamical case for the existence of a supermassive black

hole outside of our own Galaxy. Recently, a preliminary analysis of

HST stellar-dynamical data for NGC 4258 has yielded a value of

MBH consistent with the maser measurement

(Siopis et al. 2002);

this is a reassuring confirmation of the stellar-dynamical technique.

. It

is very unlikely that this mass could be

composed of a cluster of dark objects such as stellar remnants or

brown dwarfs, since the cluster density would be so large that its

lifetime against evaporation or collisions would be short compared to

the age of the galaxy

(Maoz 1995,

1998).

This makes NGC 4258 the most

compelling dynamical case for the existence of a supermassive black

hole outside of our own Galaxy. Recently, a preliminary analysis of

HST stellar-dynamical data for NGC 4258 has yielded a value of

MBH consistent with the maser measurement

(Siopis et al. 2002);

this is a reassuring confirmation of the stellar-dynamical technique.

(Greenhill et al. 1996).

NGC 4945 contains high-velocity maser clumps in a

roughly disklike arrangement, but with larger uncertainties than for NGC 4258;

the central mass is ~ 106

M

(Greenhill et al. 1996).

NGC 4945 contains high-velocity maser clumps in a

roughly disklike arrangement, but with larger uncertainties than for NGC 4258;

the central mass is ~ 106

M within a radius of 0.3 pc

(Greenhill et al. 1997).

Recently, high-velocity maser features have been detected in IC 2560

(Ishihara et al. 2001),

NGC 5793

(Hagiwara et al. 2001),

NGC 2960

(Henkel et al. 2002),

and the Circinus galaxy

(Greenhill et al. 2003),

and VLBI measurements can determine whether

the masers in these galaxies trace out Keplerian rotation curves.

Additional maser disks will continue to be found in future surveys,

although the nearby AGN population has now been surveyed so thoroughly

that it is unlikely that many more new examples will be found at

distances comparable to that of NGC 4258.

within a radius of 0.3 pc

(Greenhill et al. 1997).

Recently, high-velocity maser features have been detected in IC 2560

(Ishihara et al. 2001),

NGC 5793

(Hagiwara et al. 2001),

NGC 2960

(Henkel et al. 2002),

and the Circinus galaxy

(Greenhill et al. 2003),

and VLBI measurements can determine whether

the masers in these galaxies trace out Keplerian rotation curves.

Additional maser disks will continue to be found in future surveys,

although the nearby AGN population has now been surveyed so thoroughly

that it is unlikely that many more new examples will be found at

distances comparable to that of NGC 4258.

and

C III]

and

C III]

1909 have longer

lag times as well as narrower widths. Thus, if lag times

tlag can be measured for

multiple broad emission lines in a given galaxy, it is possible to

trace out the velocity structure of the BLR as a function of radius.

Peterson & Wandel (1999,

2000)

and Onken & Peterson (2002)

have shown that for four of the best-observed reverberation targets,

NGC 3783, NGC 5548, NGC 7469, and 3C 390.3, the relation between

tlag and emission-line width shows exactly the

dependence expected for

Keplerian motion. Within the measurement uncertainties, the emission

lines in each galaxy yield a correlation consistent with FWHM

1909 have longer

lag times as well as narrower widths. Thus, if lag times

tlag can be measured for

multiple broad emission lines in a given galaxy, it is possible to

trace out the velocity structure of the BLR as a function of radius.

Peterson & Wandel (1999,

2000)

and Onken & Peterson (2002)

have shown that for four of the best-observed reverberation targets,

NGC 3783, NGC 5548, NGC 7469, and 3C 390.3, the relation between

tlag and emission-line width shows exactly the

dependence expected for

Keplerian motion. Within the measurement uncertainties, the emission

lines in each galaxy yield a correlation consistent with FWHM

tlag0.5,

and for each galaxy the time lags and linewidths of the different

emission lines give consistent results for the central mass.

tlag0.5,

and for each galaxy the time lags and linewidths of the different

emission lines give consistent results for the central mass.

*

relation of inactive galaxies.

Nelson (2000)

performed a similar analysis for a larger sample, using [O III]

linewidths as a substitute for

*

relation of inactive galaxies.

Nelson (2000)

performed a similar analysis for a larger sample, using [O III]

linewidths as a substitute for

*,

and found similar results albeit with

additional scatter that could be attributed to some non-gravitational

motion in the narrow-line region. Some previous studies had found the

puzzling result that the AGNs seemed to have systematically lower

MBH / Mbulge ratios than inactive

galaxies

(Ho 1999,

Wandel 1999).

Since the AGNs do not appear discrepant in the

MBH -

*,

and found similar results albeit with

additional scatter that could be attributed to some non-gravitational

motion in the narrow-line region. Some previous studies had found the

puzzling result that the AGNs seemed to have systematically lower

MBH / Mbulge ratios than inactive

galaxies

(Ho 1999,

Wandel 1999).

Since the AGNs do not appear discrepant in the

MBH -

*

relation, a likely conclusion is that the bulge luminosities of the

Seyferts had been systematically overestimated, due to a combination of

their relatively large distances and the dominance of the central point

sources; possible starburst activity in the Seyferts could further

bias the photometric decompositions toward anomalously high bulge

luminosities.

*

relation, a likely conclusion is that the bulge luminosities of the

Seyferts had been systematically overestimated, due to a combination of

their relatively large distances and the dominance of the central point

sources; possible starburst activity in the Seyferts could further

bias the photometric decompositions toward anomalously high bulge

luminosities.

*

relation of Seyferts with

that of inactive galaxies suggests that the reverberation masses are

probably accurate to a factor of ~ 3 on average

(Peterson 2003).

Direct measurements of MBH in reverberation-mapped

Seyferts with

HST would be a valuable cross-check, but unfortunately only a few

bright Seyfert 1 galaxies are near enough for

rG to be resolved, and

attempts to perform stellar-dynamical measurements of the nearest

objects with HST have been thwarted by the dominance of the bright

nonstellar continuum. Gas-dynamical observations are not affected by

this problem, but HST spectra have found disturbed kinematics in the

narrow-line region, rendering gas-dynamical studies difficult or

impossible. While there have been attempts to detect cleanly rotating

gas that could be used for dynamical measurements

(Winge et al. 1999),

the presence of outflows typically prevents the use of spatially

resolved emission lines as a probe of MBH (e.g.,

Crenshaw et al. 2000).

Since there is no way to perform direct stellar- or

gas-dynamical measurements of

MBH in most reverberation-mapped AGNs,

the comparison with the MBH -

*

relation of Seyferts with

that of inactive galaxies suggests that the reverberation masses are

probably accurate to a factor of ~ 3 on average

(Peterson 2003).

Direct measurements of MBH in reverberation-mapped

Seyferts with

HST would be a valuable cross-check, but unfortunately only a few

bright Seyfert 1 galaxies are near enough for

rG to be resolved, and

attempts to perform stellar-dynamical measurements of the nearest

objects with HST have been thwarted by the dominance of the bright

nonstellar continuum. Gas-dynamical observations are not affected by

this problem, but HST spectra have found disturbed kinematics in the

narrow-line region, rendering gas-dynamical studies difficult or

impossible. While there have been attempts to detect cleanly rotating

gas that could be used for dynamical measurements

(Winge et al. 1999),

the presence of outflows typically prevents the use of spatially

resolved emission lines as a probe of MBH (e.g.,

Crenshaw et al. 2000).

Since there is no way to perform direct stellar- or

gas-dynamical measurements of

MBH in most reverberation-mapped AGNs,

the comparison with the MBH -

*

relation remains the main consistency

check that can currently be applied to the reverberation-based masses.

*

relation remains the main consistency

check that can currently be applied to the reverberation-based masses.

L0.7.

This correlation offers an extremely valuable shortcut to

estimate the BLR size, and black hole mass, in distant quasars. While

reverberation campaigns require years of intensive observations,

L(5100 Å) and

FWHM(H

L0.7.

This correlation offers an extremely valuable shortcut to

estimate the BLR size, and black hole mass, in distant quasars. While

reverberation campaigns require years of intensive observations,

L(5100 Å) and

FWHM(H )

can be measured from a single spectrum,

and then combined to yield an estimate of

MBH under the assumption

of virial motion of the BLR clouds. This is the only technique that

can routinely be applied to derive

MBH in distant AGNs, and it has

recently been the subject of intense interest, with numerous studies

focused on topics such as the MBH /

Mbulge ratio in quasars and the

search for possible differences between radio-loud and radio-quiet

objects (e.g.,

Laor 1998;

McLure & Dunlop 2001;

Lacy et al. 2001;

Laor 2001;

Oshlack, Webster, & Whiting 2002;

McLure & Dunlop 2002;

Jarvis & McLure 2002;

Shields et al. 2002).

The technique has also

been extended to make use of continuum luminosity in the rest-frame

ultraviolet combined with the velocity width of either C IV

(Vestergaard 2002)

or Mg II

(McLure & Jarvis 2002),

so that ground-based, optical spectra can be used to derive black hole

masses for high-redshift quasars.

)

can be measured from a single spectrum,

and then combined to yield an estimate of

MBH under the assumption

of virial motion of the BLR clouds. This is the only technique that

can routinely be applied to derive

MBH in distant AGNs, and it has

recently been the subject of intense interest, with numerous studies

focused on topics such as the MBH /

Mbulge ratio in quasars and the

search for possible differences between radio-loud and radio-quiet

objects (e.g.,

Laor 1998;

McLure & Dunlop 2001;

Lacy et al. 2001;

Laor 2001;

Oshlack, Webster, & Whiting 2002;

McLure & Dunlop 2002;

Jarvis & McLure 2002;

Shields et al. 2002).

The technique has also

been extended to make use of continuum luminosity in the rest-frame

ultraviolet combined with the velocity width of either C IV

(Vestergaard 2002)

or Mg II

(McLure & Jarvis 2002),

so that ground-based, optical spectra can be used to derive black hole

masses for high-redshift quasars.

5 × 108

M

5 × 108

M )

and in luminosity (

)

and in luminosity ( L

L

7 × 1045 erg s-1 at 5100

Å). Application of this method to high-redshift, high-luminosity

quasars necessarily involves a large extrapolation (see

Netzer 2003

for further discussion). These issues can be overcome if

reverberation masses can be derived for larger samples of quasars,

extending to high intrinsic luminosities and

MBH > 109

M

7 × 1045 erg s-1 at 5100

Å). Application of this method to high-redshift, high-luminosity

quasars necessarily involves a large extrapolation (see

Netzer 2003

for further discussion). These issues can be overcome if

reverberation masses can be derived for larger samples of quasars,

extending to high intrinsic luminosities and

MBH > 109

M , so

that the relations between MBH, linewidth, and

luminosity can be calibrated over a broader parameter space.

, so

that the relations between MBH, linewidth, and

luminosity can be calibrated over a broader parameter space.

1.5. Future Work and Some Open Questions

*

and MBH-Lbul correlations can be

determined definitively. To

constrain the amount of intrinsic scatter in these correlations,

realistic estimates of the measurement uncertainties are crucial.

Gas-dynamical measurements with HST and, in the future, from

ground-based telescopes with adaptive optics, will be a key

component of this pursuit. Additional measurements of black hole

masses from maser dynamics will be extremely valuable as well, if

more galaxies with Keplerian maser disks can be found.

*

and MBH-Lbul correlations can be

determined definitively. To

constrain the amount of intrinsic scatter in these correlations,

realistic estimates of the measurement uncertainties are crucial.

Gas-dynamical measurements with HST and, in the future, from

ground-based telescopes with adaptive optics, will be a key

component of this pursuit. Additional measurements of black hole

masses from maser dynamics will be extremely valuable as well, if

more galaxies with Keplerian maser disks can be found.

*.

*.

gas /

vrot

gas /

vrot

1?

Again, direct comparisons with stellar-dynamical

observations would be very useful.

1?

Again, direct comparisons with stellar-dynamical

observations would be very useful.

for

some objects (e.g.,

Shields et al. 2002),

but these measurements involve extrapolating the known correlation between

rBLR and L far beyond the mass and

luminosity ranges over which it has been calibrated locally. At

the other extreme, is there a lower limit to

Lbul or

for

some objects (e.g.,

Shields et al. 2002),

but these measurements involve extrapolating the known correlation between

rBLR and L far beyond the mass and

luminosity ranges over which it has been calibrated locally. At

the other extreme, is there a lower limit to

Lbul or

*

below which galaxies have no central black hole at all?

Searches for nuclear activity in dwarf galaxies can offer some

constraints on the population of black holes with M <

106

M

*

below which galaxies have no central black hole at all?

Searches for nuclear activity in dwarf galaxies can offer some

constraints on the population of black holes with M <

106

M .

The case of NGC 4395, a dwarf Magellanic spiral hosting a

full-fledged Seyfert 1 nucleus

(Filippenko & Sargent 1989),

demonstrates that at least some dwarf galaxies can host black holes

that would be undetectable by dynamical means.

.

The case of NGC 4395, a dwarf Magellanic spiral hosting a

full-fledged Seyfert 1 nucleus

(Filippenko & Sargent 1989),

demonstrates that at least some dwarf galaxies can host black holes

that would be undetectable by dynamical means.

*

and MBH - Lbul correlations evolve with

redshift, and how early did the black holes in the highest-redshift

quasars build up most of their mass? Reverberation mapping of

high-redshift quasars, and further calibration and testing of the

rBLR-luminosity relationship in luminous quasars, will

be of fundamental importance in answering these questions. Measurement

of the masses of black holes at high redshift, as well as the

luminosities and/or velocity dispersions of their host galaxies,

will be a major observational step toward understanding the

coevolution of black holes and their host galaxies.

*

and MBH - Lbul correlations evolve with

redshift, and how early did the black holes in the highest-redshift

quasars build up most of their mass? Reverberation mapping of

high-redshift quasars, and further calibration and testing of the

rBLR-luminosity relationship in luminous quasars, will

be of fundamental importance in answering these questions. Measurement

of the masses of black holes at high redshift, as well as the

luminosities and/or velocity dispersions of their host galaxies,

will be a major observational step toward understanding the

coevolution of black holes and their host galaxies.

Bibliography

Antonucci, R. R. J., & Miller, J. S.

1985, ApJ, 297, 621

Baker, J. C., & Hunstead, R. W.

1995, ApJ, 452, L95

Barth, A. J., Sarzi, M., Rix, H.-W., Ho, L. C.,

Filippenko, A. V., & Sargent, W. L. W.

2001, ApJ, 555, 685

Binney, J., & Tremaine, S.

1987, Galactic Dynamics (Princeton: Princeton

University Press)

Blandford, R. D., & McKee, C. F.

1982, ApJ, 255, 419

Böker, T., Laine, S., van der Marel, R. P.,

Sarzi, M., Rix, H.-W., Ho, L. C., & Shields, J. C.

2002, AJ, 123, 1389

Bower, G. A., et al.

1998, ApJ, 492, L111

Braatz, J. A., Wilson, A. S., & Henkel, C.

1996, ApJS, 106, 51

Braatz, J. A., Wilson, A. S., & Henkel, C.

1997, ApJS, 110, 321

Cappellari, M., Verolme, E. K., van der Marel,

R. P., Verdoes Kleijn, G. A., Illingworth, G. D., Franx, M., Carollo, C. M.,

& de Zeeuw, P. T. 2002, ApJ, in press

Carollo, C. M., Stiavelli, M., & Mack, J.

1998, AJ, 116, 68

Chokshi, A., & Turner, E. L.

1992, MNRAS, 259, 421

Claussen, M. J., Heiligman, G. M., & Lo, K. Y.

1984, Nature, 310, 298

Crenshaw, D. M., et al.

2000, AJ, 120, 1731

Cretton, N., Rix, H.-W., & de Zeeuw, P. T.

2000, ApJ, 536, 319

de Koff, S., Best, P., Baum, S. A., Sparks, W.,

Röttgering, H., Miley, G., Golombek, D., Macchetto, F., &

Martel, A.

2000, ApJS, 129, 33

Ferrarese, L., Ford, H. C., & Jaffe, W.

1996, ApJ, 470, 444

Ferrarese, L., & Ford, H. C.

1999, ApJ, 515, 583

Ferrarese, L. & Merritt, D.

2000, ApJ, 539, L9

Ferrarese, L., Pogge, R. W., Peterson, B. M.,

Merritt, D., Wandel, A., & Joseph, C. L.

2001, ApJ, 555, L79

Fillmore, J. A., Boroson, T. A., & Dressler, A.

1986, ApJ, 302, 208

Filippenko, A. V., & Sargent, W. L. W.

1989, ApJ, 342, L11

Ford, H. C., et al.

1994, ApJ, 435, L27

Gebhardt, K., et al.

2000a, ApJ, 539, L13

Gebhardt, K., et al.

2000b, ApJ, 543, L5

Greenhill, L. J., Jiang, D. R., Moran, J. M., Reid,

M. J., Lo, K. Y., & Claussen, M. J.

1995, ApJ, 440, 619

Greenhill, L. J., Gwinn, C. R., Antonucci, R., &

Barvainis, R.

1996, ApJ, 472, L21

Greenhill, L. J., Moran, J. M., & Herrnstein,

J. R.

1997, ApJ, 481, L23

Greenhill, L. J., et al.

2002, ApJ, 565, 836

Greenhill, L. J., Kondratko, P. T., Lovell,

J. E. J., Kuiper, T. B. H., Moran, J. M., Jauncey, D. L., & Baines,

G. P. 2003, ApJ, in press

Hagiwara, Y., Diamond, P. J., Nakai, N., &

Kawabe, R.

2001, ApJ, 560, 119

Harms, R. J., et al.

1994, ApJ, 435, L35

Henkel, C., Braatz, J. A., Greenhill, L. J., &

Wilson, A. S.

2002, A&A, 394, L23

Ho, L.C. 1999, in

Observational Evidence for Black Holes in the Universe,

ed. S.K. Chakrabarti (Dordrecht: Kluwer), 157

Ho, L.C., Sarzi, M., Rix, H., Shields, J.C.,

Rudnick, G., Filippenko, A.V., & Barth, A.J.

2002, PASP, 114, 137

Ishihara, Y., Nakai, N., Iyomoto, N., Makishima, K.,

Diamond, P., & Hall, P.

2001, PASJ, 53, 215

Iwasawa, K., et al.

1996, MNRAS, 282, 1038

Iwasawa, K., Maloney, P. R., & Fabian, A. C.

2002, MNRAS, 336, L71

Jaffe, W., Ford, H. C., Ferrarese, L., van den

Bosch, F., & O'Connell, R. W.

1993, Nature, 364, 213

Jaffe, W., Ford, H. C., Tsvetanov, Z.,

Ferrarese, L., & Dressel, L. 1999, in

ASP Conf. Series Vol. 182, Galaxy Dynamics, edited by

D. Merritt, J. A. Sellwood, & M. Valluri (San Francisco: ASP), 13

Jarvis, M. J., & McLure, R. J.

2002, MNRAS, 336, L38

Kaspi, S., Smith, P. S., Netzer, H., Maoz, D.,

Jannuzi, B. T., & Giveon, U.

2000, ApJ, 533, 631

Kaspi, S., Netzer, H., Maoz, D., Shemmer, O.,

Brandt, W. N., & Schneider, D. P. 2003, in

Active Galactic Nuclei: from Central Engine

to Host Galaxy, edited by S. Collin et al. (San Francisco: ASP)

Koda, J., & Wada, K.

2002, A&A, 396, 867

Kormendy, J., & Gebhardt, K. 2001, in

The 20th Texas Symposium on Relativistic

Astrophysics, ed. J. Craig Wheeler & Hugo Martel (New York:

AIP), 363

Kormendy, J., & Richstone, D.

1995, ARA&A, 33, 581

Kormendy, J., & Westpfahl, D. J.

1989, ApJ, 338, 752

Kotanyi, C. G., & Ekers, R. D.

1979, A&A, 73, L1

Krolik, J. H.

2001, ApJ, 551, 72

Lacy, M., Laurent-Muehleisen, S. A., Ridgway, S. E.,

Becker, R. H., & White, R. L.

2001, ApJ, 551, L17

Laor, A.

1998, ApJ, 505, L83

Laor, A.

2001, ApJ, 553, 677

Macchetto, F., Marconi, A., Axon, D. J.,

Capetti, A., Sparks, W., & Crane, P.

1997, ApJ, 489, 579

Maciejewski, W. 2003, in

Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series, Vol. 1: Coevolution of Black

Holes and Galaxies, ed. L. C. Ho (Pasadena: Carnegie Observatories,

http://www.ociw.edu/ociw/symposia/series/symposium1/proceedings.html)

Maciejewski, W., & Binney, J.

2001, MNRAS, 323, 831

Makishima, K., et al.

1994, PASJ, 46, L77

Maoz, E.

1995, ApJ, 447, L91

Maoz, E.

1998, ApJ, 494, L181

Marconi, A., Capetti, A., Axon, D. J.,

Koekemoer, A., Macchetto, D., & Schreier, E. J.

2001, ApJ, 549, 915

Marconi, A., et al.

2003, ApJ, in press

McLure, R. J., & Dunlop, J. S.

2001, MNRAS, 327, 199

McLure, R. J., & Dunlop, J. S.

2002, MNRAS, 331, 795

McLure, R. J., & Jarvis, M. J.

2002, MNRAS, in press

Merritt, D., & Ferrarese, L. 2001, in

The Central Kiloparsec of Starbursts and AGNs,

ed. J. H. Knapen et al. (San Francisco: ASP), 335

Miyoshi, M., Moran, J., Herrnstein, J., Greenhill,

L., Nakai, N., Diamond, P., & Inoue, M.

1995, Nature, 373, 127

Moran, J. M., Greenhill, L. J., &

Herrnstein, J. R.

1999, Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy, 20, 165

Nakai, N., Inoue, M., & Miyoshi, M.

1993, Nature, 361, 6407

Nandra, K., George, I. M., Mushotzky, R. F., Turner,

T. J., & Yaqoob, T.

1997, ApJ, 477, 602

Nelson, C. H.

2000, ApJ, 544, L91, 199

Netzer, H.

2003, ApJ, 583, L5

Onken, C. A., & Peterson, B. M.

2002, ApJ, 572, 746

Oshlack, A. Y. K. N., Webster, R. L., & Whiting,

M. T.

2002, ApJ, 576, 81

Peterson, B. M. 2001, in

Advanced Lectures on the Starburst-AGN Connection,

ed. I. Aretxaga, D. Kunth, & R. Mújica (Singapore: World

Scientific), 3

Peterson, B. M. 2003, in

Active Galactic Nuclei: from Central Engine

to Host Galaxy, edited by S. Collin et al. (San Francisco: ASP)

Peterson, B. M., & Wandel, A.

1999, ApJ, 521, L95

Peterson, B. M., & Wandel, A.

2000, ApJ, 540, L13

Rees, M. J.

1984, ARA&A, 22, 471

Sadler, E. M., & Gerhard, O. E.

1985, MNRAS, 214, 177

Salucci, P., Ratnam, C., Monaco, P., &

Danese, L.

2000, MNRAS, 317, 488

Salpeter, E. E.

1964, ApJ, 140, 796

Sargent, W. L. W., Young, P. J., Boksenberg, A.,

Shortridge, K., Lynds, C. R., & Hartwick, F. D. A.

1978, ApJ, 221, 731

Sarzi, M., Rix, H.-W., Shields, J. C., Rudnick, G.,

Ho, L. C., McIntosh, D. H., Filippenko, A. V., & Sargent, W. L. W.

2001, ApJ, 550, 65

Sarzi, M. et al.

2002, ApJ, 567, 237

Shields, G. A., Gebhardt, K., Salviander, S., Wills,

B., Xie, B., Brotherton, M. S., Yuan, J., Dietrich, M.

2002, ApJ, 583, 124

Siopis, C., et al.

2002, BAAS, 201, 6802

Small, T. A., & Blandford, R. D.

1992, MNRAS, 259, 725

Soltan, A.

1982, MNRAS, 200, 115

Tanaka, Y., et al.

1995, Nature, 375, 659

Tran, H. D., Tsvetanov, Z., Ford, H. C., Davies, J.,

Jaffe, W., van den Bosch, F. C., & Rest, A.

2001, AJ, 121, 2928

Tremaine, S., et al.

2002, ApJ, 574, 740

van der Marel, R. P.

1994, ApJ, 432, L91

Verdoes Kleijn, G. A., Baum, S. A., de Zeeuw, P. T.,

& O'Dea, C. P.

1999, AJ, 118, 2592

Verdoes Kleijn, G. A., van der Marel, R. P.,

Carollo, C. M., & de Zeeuw, P. T.

2000, AJ, 120, 1221

Verdoes Kleijn, G. A., van der Marel, R. P., de

Zeeuw, P. T., Noel-Storr, J., & Baum, S. A.

2002, AJ, in press

Verdoes Kleijn, G. A., van der Marel, R. P., &

Noel-Storr, J. 2003, in

Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series, Vol. 1:

Coevolution of Black Holes and Galaxies, ed. L. C. Ho (Pasadena:

Carnegie Observatories,

http://www.ociw.edu/ociw/symposia/series/symposium1/proceedings.html)

Vestergaard, M.

2002, ApJ, 571, 733

van der Marel, R. P., & van den Bosch, F. C.

1998, AJ, 116, 2220

Wada, K., Meurer, G., & Norman, C. A.

2002, ApJ, 577, 197

Walcher, C. J., Häring, N., Böker, T.,

Rix, H.-W., van der Marel, R. P., & Gerssen, J. 2003, in

Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series, Vol. 1: Coevolution of Black

Holes and Galaxies, ed. L. C. Ho (Pasadena: Carnegie Observatories,

http://www.ociw.edu/ociw/symposia/series/symposium1/proceedings.html)

Wandel, A.

1999, ApJ, 519, L39

Wandel, A., Peterson, B. M., & Malkan, M. A.

1999, ApJ, 526, 579

Watson, W. D. & Wallin, B. K.

1994, ApJ, 432, L35

Whiting, M. T., Webster, R. L., & Francis,

P. J.

2001, MNRAS, 323, 718

Wilkes, B. J., Schmidt, G. D., Smith, P. S.,

Mathur, S., & McLeod, K. K.

1995, ApJ, 455, L13

Winge, C., Axon, D. J., Macchetto, F. D., Capetti,

A., & Marconi, A.

1999, ApJ, 519, 134

Young, P. J., Westphal, J. A., Kristian, J.,

Wilson, C. P., & Landauer, F. P.

1978, ApJ, 221, 721

Zel'dovich, Ya. B., & Novikov, I. D.

1964, Sov. Phys. Dokl., 158, 811