As summarized in Section 2, the interstellar extinction, polarization, scattering, the near, mid, and far-IR emission and the 3.3-11.3 µm PAH emission features point to the existence of two dust populations in interstellar space:

There exists a population of large grains

with a

250

Å. Illuminated by the general

interstellar radiation field (ISRF), these grains, defined

as "cold dust", obtain equilibrium temperatures of 15 K

250

Å. Illuminated by the general

interstellar radiation field (ISRF), these grains, defined

as "cold dust", obtain equilibrium temperatures of 15 K

T

T

25 K and emit

strongly at

wavelengths

25 K and emit

strongly at

wavelengths

60

µm. These grains are

responsible for the near-IR/optical extinction, scattering,

polarization and the emission at

60

µm. These grains are

responsible for the near-IR/optical extinction, scattering,

polarization and the emission at

60 µm.

60 µm.

The equilibrium temperature T for a large grain of spherical radius a is determined by balancing absorption and emission:

|

(1) |

where Cabs(a,

) is the absorption

cross section for a grain with size a at wavelength

) is the absorption

cross section for a grain with size a at wavelength

, c is the

speed of light,

B

, c is the

speed of light,

B (T) is the Planck function at temperature

T, and

u

(T) is the Planck function at temperature

T, and

u is the energy density of the radiation field.

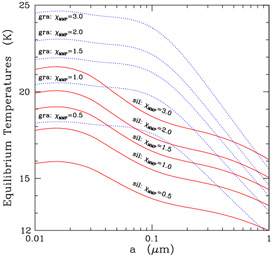

In Figure 1 we display

these "equilibrium" temperatures for graphitic and silicate grains

as a function of size in environments with various UV intensities.

is the energy density of the radiation field.

In Figure 1 we display

these "equilibrium" temperatures for graphitic and silicate grains

as a function of size in environments with various UV intensities.

|

Figure 1. Equilibrium temperatures for graphite (dotted lines) and silicate grains (solid lines) in environments with various starlight intensities (in units of the Mathis, Mezger, & Panagia 1983 [MMP] solar neighbourhood ISRF). Taken from Li & Draine (2001b). |

There exists a population of ultrasmall grains with

a  250

Å. These grains have energy

contents smaller or comparable to the energy of a single

starlight photon. As a result, a single photon can heat

a very small grain to a peak temperature much higher than

its "steady-state" temperature and the grain then rapidly

cools down to a temperature below the "steady-state"

temperature before the next photon absorption event.

Stochastic heating by absorption of starlight therefore

results in transient "temperature spikes", during which

much of the energy deposited by the starlight photon is

reradiated in the IR - because of this, we call these

ultrasmall grains "warm dust".

15

These grains are responsible for the far-UV extinction rise

and the emission at

250

Å. These grains have energy

contents smaller or comparable to the energy of a single

starlight photon. As a result, a single photon can heat

a very small grain to a peak temperature much higher than

its "steady-state" temperature and the grain then rapidly

cools down to a temperature below the "steady-state"

temperature before the next photon absorption event.

Stochastic heating by absorption of starlight therefore

results in transient "temperature spikes", during which

much of the energy deposited by the starlight photon is

reradiated in the IR - because of this, we call these

ultrasmall grains "warm dust".

15

These grains are responsible for the far-UV extinction rise

and the emission at

60 µm

(including the 3.3-11.3 µm PAH emission features),

dominate the photoelectric heating of interstellar

gas (see Section 2.5 in

Li 2004a),

and provide most of the grain surface area in the diffuse ISM.

60 µm

(including the 3.3-11.3 µm PAH emission features),

dominate the photoelectric heating of interstellar

gas (see Section 2.5 in

Li 2004a),

and provide most of the grain surface area in the diffuse ISM.

Since ultrasmall grains will not maintain "equilibrium temperatures", we need to calculate their temperature (energy) probability distribution functions in order to calculate their time-averaged IR emission spectrum. There have been a number of studies on this topic since the pioneering work of Greenberg (1968). A recent extensive investigation was carried out by Draine & Li (2001). We will not go into details in this review, but just refer those who are interested to Draine & Li (2001) and a recent review article of Li (2004a).

For illustration, we show in Figure 2

the energy probability distribution functions dP / dlnE

(where dP is the probability

that a grain will have vibrational energy in interval

[E, E + dE]) for PAHs with radii

a = 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 150, 200, 300 Å

illuminated by the general ISRF.

It is seen that very small grains (a

100 Å)

have a very broad P(E), and the smallest grains

(a < 30 Å) have an appreciable probability

P0

of being found in the vibrational ground state E = 0.

As the grain size increases, P(E) becomes narrower,

so that it can be approximated by

a delta function for a > 250 Å.

16

However, for radii as large as a = 200 Å,

grains have energy distribution functions

which are broad enough that the emission spectrum

deviates noticeably from the emission spectrum for

grains at a single "steady-state" temperature T,

as shown in Figure 3.

For accurate computation of IR emission spectra

it is therefore important to properly calculate

the energy distribution function P(E),

including grain sizes which are large enough that the average

thermal energy content exceeds a few eV.

100 Å)

have a very broad P(E), and the smallest grains

(a < 30 Å) have an appreciable probability

P0

of being found in the vibrational ground state E = 0.

As the grain size increases, P(E) becomes narrower,

so that it can be approximated by

a delta function for a > 250 Å.

16

However, for radii as large as a = 200 Å,

grains have energy distribution functions

which are broad enough that the emission spectrum

deviates noticeably from the emission spectrum for

grains at a single "steady-state" temperature T,

as shown in Figure 3.

For accurate computation of IR emission spectra

it is therefore important to properly calculate

the energy distribution function P(E),

including grain sizes which are large enough that the average

thermal energy content exceeds a few eV.

|

Figure 2. The energy probability distribution functions for charged carbonaceous grains (a = 5 Å [C60H20], 10Å [C480H120], 25Å [C7200H1800], 50, 75, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300Å) illuminated by the general ISRF. The discontinuity in the 5, 10, and 25Å curves is due to the change of the estimate for grain vibrational "temperature" at the 20th vibrational mode (see Draine & Li 2001). For 5, 10, and 25Å a dot indicates the first excited state, and P0 is the probability of being in the ground state. Taken from Li & Draine (2001b). |

|

Figure 3. Infrared emission spectra for

small carbonaceous grains of various sizes heated by the general ISRF,

calculated using the full energy distribution function

P(E) (solid lines); also shown (broken lines) are spectra

computed for grains at the "equilibrium" temperature T.

Transient heating effects lead to

significantly more short wavelength emission for a

|

Nano-sized interstellar diamond and TiC grains

have been identified in primitive meteorites based on

isotopic anomaly analysis. Exposed to the general ISRF,

these grains are subject to single-photon heating

and should of course be classified as "warm dust".

But we should note that they are not representative of

the bulk interstellar dust (see Section 5.4 and Section 5.5 in

Li 2004a).

The carriers of the ERE (see Section 2.8) and the 2175 Å

extinction hump (see Section 2.4) are also in the single-photon

heating regime. Therefore, they can also be classified as

"warm dust". As a matter of fact, the latter is attributed

to PAHs (see Section 2.4). On the other hand, the Ulysses and Galileo

spacecrafts have detected a substantial number of

large interstellar grains with a

1 µm

(Grün et al. 1994),

much higher than expected for

the average interstellar dust distribution.

In the ISM, these should of course be considered

as "cold dust" or "very cold dust" with T < 10 K.

But we note that the reported mass of these large grains

is difficult to reconcile with the interstellar extinction

and interstellar elemental abundances.

1 µm

(Grün et al. 1994),

much higher than expected for

the average interstellar dust distribution.

In the ISM, these should of course be considered

as "cold dust" or "very cold dust" with T < 10 K.

But we note that the reported mass of these large grains

is difficult to reconcile with the interstellar extinction

and interstellar elemental abundances.