We shall now move on to the more realistic case of a multi-component

universe consisting of radiation and collisionless dark matter.

(For the moment we are ignoring the baryons, which we will study in

Sec. 6). It is convenient to use y =

a / aeq as independent variable

rather than the time coordinate. The background expansion of the

universe described by the function a(t) can be

equivalently expressed (in terms of the conformal time

) as

) as

|

(70) |

It is also useful to define a critical wave number kc by:

|

(71) |

which essentially sets the comoving scale corresponding to

matter-radiation equality. Note that 2x = kc

and y

and y

kc

kc

in the

radiation dominated phase while y = (1/4)(kc

in the

radiation dominated phase while y = (1/4)(kc

)2

in the matter dominated phase.

)2

in the matter dominated phase.

We now manipulate Eqs. (52), (55), (56), (57) governing the growth of perturbations by essentially eliminating the velocity. This leads to the three equations

|

(72) |

|

(73) |

|

(74) |

for the three unknowns  ,

,

m,

m,

R. Given

suitable initial conditions we can solve these equations to determine

the growth of perturbations. The initial conditions need to imposed very

early on when the modes are much bigger than the Hubble radius which

corresponds to the y << 1, k

R. Given

suitable initial conditions we can solve these equations to determine

the growth of perturbations. The initial conditions need to imposed very

early on when the modes are much bigger than the Hubble radius which

corresponds to the y << 1, k

0 limit. In this

limit, the equations become:

0 limit. In this

limit, the equations become:

|

(75) |

We will take

(yi,

k) =

(yi,

k) =

i(k)

as given value, to be determined by

the processes that generate the initial perturbations. First equation in

Eq. (75) shows that we can take

i(k)

as given value, to be determined by

the processes that generate the initial perturbations. First equation in

Eq. (75) shows that we can take

R =

-2

R =

-2 i for

yi

i for

yi  0.

Further Eq. (53) shows that adiabaticity is respected

at these scales and we can take

0.

Further Eq. (53) shows that adiabaticity is respected

at these scales and we can take

m = (3/4)

m = (3/4)

R = -(3/2)

R = -(3/2)

i;.

The exact equation Eq. (72) determines

i;.

The exact equation Eq. (72) determines

' if

(

' if

( ,

,

m,

m,

R) are

given. Finally we use the last two equations to set

R) are

given. Finally we use the last two equations to set

'm =

3

'm =

3 ',

',

'R =

4

'R =

4 '.

Thus we take the initial conditions at some y =

yi << 1 to be:

'.

Thus we take the initial conditions at some y =

yi << 1 to be:

|

(76) |

with  'm(yi, k) =

3

'm(yi, k) =

3 '(yi, k);

'(yi, k);

'R(yi, k) =

4

'R(yi, k) =

4 '(yi, k).

'(yi, k).

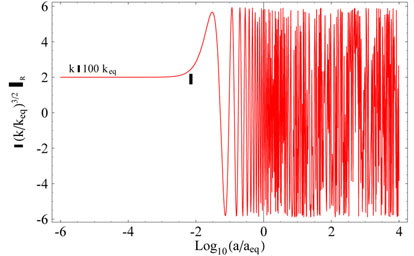

Given these initial conditions, it is fairly easy to integrate the equations forward in time and the numerical results are shown in Figs 2, 3, 4, 5. (In the figures keq is taken to be aeqHeq.) To understand the nature of the evolution, it is, however, useful to try out a few analytic approximations to Eqs. (72) – (74) which is what we will do now.

4.1 . Evolution for

>>

dH

>>

dH

Let us begin by considering very large wavelength modes corresponding to

the k

0 limit. In this case

adiabaticity is respected and we can set

0 limit. In this case

adiabaticity is respected and we can set

R

R

(4/3)

(4/3) m.

Then Eqs. (72), (73) become

m.

Then Eqs. (72), (73) become

|

(77) |

Differentiating the first equation and using the second to eliminate

m, we get a

second order equation for

m, we get a

second order equation for

. Fortunately, this

equation has an exact solution

. Fortunately, this

equation has an exact solution

|

(78) |

[There is simple way of determining such an exact solution, which we

will describe in Sec. 4.4.]. The initial condition on

R is chosen

such that it goes to

-2

R is chosen

such that it goes to

-2 i initially.

The solution shows that, as long as the mode is bigger than the Hubble

radius, the potential changes very little; it is constant initially as

well as in the final matter dominated phase. At late times (y

>> 1) we

see that

i initially.

The solution shows that, as long as the mode is bigger than the Hubble

radius, the potential changes very little; it is constant initially as

well as in the final matter dominated phase. At late times (y

>> 1) we

see that

(9/10)

(9/10)

i so that

i so that

decreases only by a

factor (9/10) during the entire evolution if k

decreases only by a

factor (9/10) during the entire evolution if k

0 is a valid

approximation.

0 is a valid

approximation.

4.2. Evolution for

<<

dH in the radiation dominated phase

<<

dH in the radiation dominated phase

When the mode enters Hubble radius in the radiation dominated phase, we

can no longer ignore the pressure terms. The

pressure makes radiation density contrast oscillate and the

gravitational potential, driven by this, also oscillates with a decay in

the overall amplitude. An approximate procedure to describe this phase

is to solve the coupled

R -

R -

system, ignoring

system, ignoring

m which is

sub-dominant and then determine

m which is

sub-dominant and then determine

m using the

form of

m using the

form of  .

.

When  m is

ignored, the problem reduces to the one solved earlier in Eqs (64), (65)

with w = 1/3 giving

m is

ignored, the problem reduces to the one solved earlier in Eqs (64), (65)

with w = 1/3 giving

= 3. Since

J3/2

can be expressed in terms of trigonometric functions, the solution given

by Eq. (64) with

= 3. Since

J3/2

can be expressed in terms of trigonometric functions, the solution given

by Eq. (64) with  = 3, simplifies to

= 3, simplifies to

|

(79) |

Note that as y  0, we have

0, we have  =

=

i,

i,

' = 0. This solution

shows that once the mode enters the Hubble radius, the potential decays

in an oscillatory manner. For ly >> 1, the potential becomes

' = 0. This solution

shows that once the mode enters the Hubble radius, the potential decays

in an oscillatory manner. For ly >> 1, the potential becomes

-3

-3 i

(ly)-2 cos(ly). In the same limit,

we get from Eq. (65) that

i

(ly)-2 cos(ly). In the same limit,

we get from Eq. (65) that

|

(80) |

(This is analogous to Eq. (68) for the radiation dominated case.) This oscillation is seen clearly in Fig 3. and Fig. 4 (left panel). The amplitude of oscillations is accurately captured by Eq. (80) for k = 100keq mode but not for k = keq; this is to be expected since the mode is not entering in the radiation dominated phase.

|

Figure 3. Evolution of

|

Let us next consider matter perturbations during this phase. They grow, driven by the gravitational potential determined above. When y << 1, Eq. (73) becomes:

|

(81) |

The  is essentially

determined by radiation and satisfies Eq. (61); using this, we can

rewrite Eq. (81) as

is essentially

determined by radiation and satisfies Eq. (61); using this, we can

rewrite Eq. (81) as

|

(82) |

The general solution to the homogeneous part of Eq. (82) (obtained by ignoring the right hand side) is (c1 + c2 lny); hence the general solution to this equation is

|

(83) |

For y << 1 the growing mode varies as lny and

dominates over the rest; hence we conclude that,

matter, driven by  ,

grows logarithmically during the radiation dominated phase for modes

which are inside the Hubble radius.

,

grows logarithmically during the radiation dominated phase for modes

which are inside the Hubble radius.

4.3. Evolution in the matter dominated phase

Finally let us consider the matter dominated phase, in which we can ignore the radiation and concentrate on Eq. (72) and Eq. (73). When y >> 1 these equations become:

|

(84) |

These have a simple solution which we found earlier (see Eq. (69)):

|

(85) |

In this limit, the matter perturbations grow linearly with expansion:

m

m

y

y

a. In fact

this is the most dominant growth mode in the linear perturbation

theory.

a. In fact

this is the most dominant growth mode in the linear perturbation

theory.

4.4. An alternative description of matter-radiation system

Before proceeding further, we will describe an alternative procedure for

discussing the perturbations in dark matter and radiation, which has

some advantages. In the formalism we used above, we used

perturbations in the energy density of radiation

( R) and

matter (

R) and

matter ( m)

as the dependent variables. Instead, we now use perturbations in the

total energy density,

m)

as the dependent variables. Instead, we now use perturbations in the

total energy density,

and

the perturbations in the entropy per particle,

and

the perturbations in the entropy per particle,

as the new dependent

variables. In terms of

as the new dependent

variables. In terms of

R,

R,

m, these

variables are defined as:

m, these

variables are defined as:

|

(86) |

|

(87) |

Given the equations for

R,

R,

m, one can

obtain the corresponding equations for the new variables

(

m, one can

obtain the corresponding equations for the new variables

( ,

,

) by

straight forward algebra. It is convenient to express them as two

coupled equations for

) by

straight forward algebra. It is convenient to express them as two

coupled equations for  and

and  . After some direct

but a bit tedious algebra, we get:

. After some direct

but a bit tedious algebra, we get:

|

(88) |

|

(89) |

where we have defined

|

(90) |

These equations show that the entropy perturbations and gravitational

potential (which is directly related to total energy density

perturbations) act as sources for each other. The coupling between the

two arises through the right hand sides of Eq. (88) and

Eq. (89). We also see that if we set

= 0 as an initial

condition, this is preserved to

= 0 as an initial

condition, this is preserved to

(k4) and

- for long wave length modes - the

(k4) and

- for long wave length modes - the

evolves independent of

evolves independent of

. The

solutions to the coupled equations obtained by numerical integration is

shown in Fig. (2) right panel. The entropy

perturbation

. The

solutions to the coupled equations obtained by numerical integration is

shown in Fig. (2) right panel. The entropy

perturbation

0 till the mode

enters Hubble radius and grows afterwards tracking either

0 till the mode

enters Hubble radius and grows afterwards tracking either

R or

R or

m whichever

is the dominant energy density perturbation. To illustrate the behaviour of

m whichever

is the dominant energy density perturbation. To illustrate the behaviour of

, let us consider the

adiabatic perturbations at large scales with

, let us consider the

adiabatic perturbations at large scales with

0, k

0, k

0; then the

gravitational potential satisfies the equation:

0; then the

gravitational potential satisfies the equation:

|

(91) |

which has the two independent solutions:

|

(92) |

both of which diverge as y

0.

We need to combine these two solutions to find the general solution,

keeping in mind that the general solution should be

nonsingular and become a constant (say, unity) as y

0.

We need to combine these two solutions to find the general solution,

keeping in mind that the general solution should be

nonsingular and become a constant (say, unity) as y

0. This fixes

the linear combination uniquely:

0. This fixes

the linear combination uniquely:

|

(93) |

Multiplying by

i we get the

solution that was found earlier (see Eq. (78)).

Given the form of

i we get the

solution that was found earlier (see Eq. (78)).

Given the form of  and

and

0 we can determine all

other quantities. In particular, we get:

0 we can determine all

other quantities. In particular, we get:

|

(94) |

The corresponding velocity field, which we quote for future reference, is given by:

|

(95) |

We conclude this section by mentioning another useful result related to

Eq. (88). When

0, the equation for

0, the equation for

can be re-expressed as

can be re-expressed as

|

(96) |

where we have defined:

|

(97) |

(The i factor arises because of converting a gradient to the k

space; of course, when everything is done correctly, all physical

quantities will be real.) Other equivalent alternative forms for

, which are useful are:

, which are useful are:

|

(98) |

For modes which are bigger than the Hubble radius, Eq. (96) shows that

is conserved.

When

is conserved.

When  = constant, we can

integrate Eq. (98) easily to obtain:

= constant, we can

integrate Eq. (98) easily to obtain:

|

(99) |

This is the easiest way to obtain the solution in Eq. (78).

The conservation law for  also allows us to understand in a simple manner our previous result that

also allows us to understand in a simple manner our previous result that

only deceases by a factor

(9/10) when the mode remains bigger than Hubble radius as we evolve

the equations from y << 1 to y >> 1. Let us

compare the values of

only deceases by a factor

(9/10) when the mode remains bigger than Hubble radius as we evolve

the equations from y << 1 to y >> 1. Let us

compare the values of

early in the radiation

dominated phase and late in the matter

dominated phase. From the first equation in Eq. (98), [using

early in the radiation

dominated phase and late in the matter

dominated phase. From the first equation in Eq. (98), [using

'

'

0 we find that, in

the radiation dominated phase,

0 we find that, in

the radiation dominated phase,

(1/2)

(1/2)

i +

i +

i = (3/2)

i = (3/2)

i; late in

the matter dominated phase,

i; late in

the matter dominated phase,

(2/3)

(2/3) f +

f +

f = (5/3)

f = (5/3)

f. Hence the

conservation of

f. Hence the

conservation of  gives

gives

f =

(3/5)(3/2)

f =

(3/5)(3/2) i

= (9/10)

i

= (9/10)  i

which was the result obtained earlier. The expression in

Eq. (99) also works at late times in the

i

which was the result obtained earlier. The expression in

Eq. (99) also works at late times in the

dominated or

curvature dominated universe.

dominated or

curvature dominated universe.

One key feature which should be noted in the study of linear

perturbation theory is the different amount of growths for

,

,

R and

R and

m. The

m. The

either changes very

little or decays; the

either changes very

little or decays; the

R grows in

amplitude only by a factor of few. The

physical reason, of course, is that the amplitude is frozen at

super-Hubble scales and the pressure prevents the growth at sub-Hubble

scales. In contrast,

R grows in

amplitude only by a factor of few. The

physical reason, of course, is that the amplitude is frozen at

super-Hubble scales and the pressure prevents the growth at sub-Hubble

scales. In contrast,

m, which is

pressureless, grows logarithmically in the radiation dominated era and

linearly during the matter dominated era. Since the later phase lasts

for a factor of 104 in expansion, we get a fair amount of

growth in

m, which is

pressureless, grows logarithmically in the radiation dominated era and

linearly during the matter dominated era. Since the later phase lasts

for a factor of 104 in expansion, we get a fair amount of

growth in  m.

m.