Although bars are ubiquitous and might account for a significant fraction of a galaxy total luminosity, only recently studies dedicated to a more detailed modelling of the structural properties of bars started to come out more often (see e.g. [54, 78, 36]). This is partially because of the significant increase in complexity when one includes another component in the structural modelling of disc galaxies. These studies usually make use of the full data contained in 2D galaxy images, rather than only 1D surface brightness profiles, in order to obtain more accurate results. The rise in complexity thus usually means that automated procedures become much less reliable. In [36], BUDDA v2.1 [23] is used to individually fit galaxy images with model images that include up to three components: a Sérsic bulge, an exponential disc and a bar. Bars are modelled as a set of concentric generalised ellipses [8], with same position angle and ellipticity:

| (1) |

where x and y are the pixel coordinates of the ellipse

points, a and b are the extent of its semi-major and

semi-minor axes, respectively, and c is a shape parameter. Bars

are better described by boxy ellipses (i.e. with c > 2). The

surface brightness profile of the model bar is described as a Sérsic

profile, as bulges. The Sérsic index of bars

nBar is often in the range

0.5-1,

with lower values representing flatter profiles. Another bar parameter

fitted by the code is the length of the bar semi-major axis

LBar, after which the bar light profile is

simply truncated and drops to zero.

0.5-1,

with lower values representing flatter profiles. Another bar parameter

fitted by the code is the length of the bar semi-major axis

LBar, after which the bar light profile is

simply truncated and drops to zero.

Similar fits were individually done to

1000 galaxies in a sample

carefully drawn from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS - see

[42]).

The sample spans from elliptical

to bulgeless galaxies, with stellar masses above 1010

M

1000 galaxies in a sample

carefully drawn from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS - see

[42]).

The sample spans from elliptical

to bulgeless galaxies, with stellar masses above 1010

M (k-corrected

z-band absolute magnitudes

(k-corrected

z-band absolute magnitudes

-20 AB mag), at a typical

redshift of 0.05, and includes

-20 AB mag), at a typical

redshift of 0.05, and includes

300 barred

galaxies. All galaxies are very close to face-on

(axial ratio

300 barred

galaxies. All galaxies are very close to face-on

(axial ratio  0.9) and do not show morphological perturbations,

thus assuring that dust extinction is minimised and that the sample is

suitable for image decomposition. This also avoids the uncertainties in

obtaining deprojected quantities. Fits were done in g, r

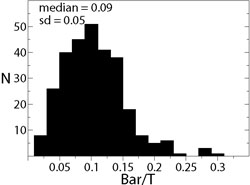

and i-band images. The distributions of several bar structural

parameters obtained in this work from the i-band images are shown

in Figs. 1 and 2.

0.9) and do not show morphological perturbations,

thus assuring that dust extinction is minimised and that the sample is

suitable for image decomposition. This also avoids the uncertainties in

obtaining deprojected quantities. Fits were done in g, r

and i-band images. The distributions of several bar structural

parameters obtained in this work from the i-band images are shown

in Figs. 1 and 2.

|

|

|

|

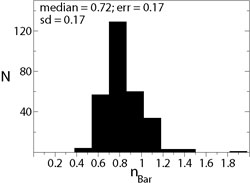

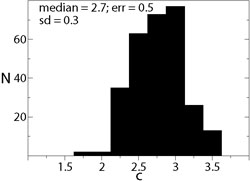

Figure 2. Same as Fig. 1, but for bar-to-total luminosity fraction, bar Sérsic index, and bar boxyness [parameterised as c - see Eq. (1)]. |

|

Models of bar formation and evolution

should be in agreement with these results. Conversely, models where bar

properties are imposed can use these results as a guide in the

adjustment of the bar properties. One must note, however, that, due to

the relatively poor spatial resolution of the SDSS, these results are

biased against bars shorter than LBar

2-3 kpc, typically

seen in very late type spirals (later than Sc

[25]).

These results are thus

representative of the prototypical, bonafide bars seen mostly in early

type spirals (earlier than Sc) and lenticulars. Interestingly, the

median bar ellipticity is

2-3 kpc, typically

seen in very late type spirals (later than Sc

[25]).

These results are thus

representative of the prototypical, bonafide bars seen mostly in early

type spirals (earlier than Sc) and lenticulars. Interestingly, the

median bar ellipticity is

20% higher than the

value found via ellipse fitting to galaxy images in

[59].

This is exactly what was predicted in

[36]

as ellipse fits

systematically underestimate the true bar ellipticity due to the

dilution of the bar isophotes by the rounder, axisymmetric light

distribution of bulge and disc. When fitting ellipses to galaxy images

one does not separate the contributions to the total galaxy light

distribution from the different components, but this is done in image

fitting with different models for each component. This shows that

results based on the ellipticity of bars measured via ellipse fitting

should be considered with this caveat in mind. For instance, there is an

indication from ellipse fits that, for faint galaxies, disk-dominated

galaxies have more eccentric bars than bulge-dominated galaxies

[9].

It it is not clear, however, if

this result holds if the axisymmetric light contribution from bulge and

disk is taken into account. Figure 1 also shows

that most of these bars have a semi-major axis between 3 and 6 kpc (but

with a long tail to longer bars), and that bars do not extend further

than

20% higher than the

value found via ellipse fitting to galaxy images in

[59].

This is exactly what was predicted in

[36]

as ellipse fits

systematically underestimate the true bar ellipticity due to the

dilution of the bar isophotes by the rounder, axisymmetric light

distribution of bulge and disc. When fitting ellipses to galaxy images

one does not separate the contributions to the total galaxy light

distribution from the different components, but this is done in image

fitting with different models for each component. This shows that

results based on the ellipticity of bars measured via ellipse fitting

should be considered with this caveat in mind. For instance, there is an

indication from ellipse fits that, for faint galaxies, disk-dominated

galaxies have more eccentric bars than bulge-dominated galaxies

[9].

It it is not clear, however, if

this result holds if the axisymmetric light contribution from bulge and

disk is taken into account. Figure 1 also shows

that most of these bars have a semi-major axis between 3 and 6 kpc (but

with a long tail to longer bars), and that bars do not extend further

than  3 times the disc

scalelength h, or

3 times the disc

scalelength h, or

1r24 (the radius at which the galaxy surface

brightness reaches 24 mag arcsec-2 in the r-band

- see also

[29]).

Figure 2 shows that a typical bar is responsible for

1r24 (the radius at which the galaxy surface

brightness reaches 24 mag arcsec-2 in the r-band

- see also

[29]).

Figure 2 shows that a typical bar is responsible for

10% of the total

galaxy light, and has a quite flat luminosity

profile. Interestingly, one also sees that, indeed, bars have very boxy

shapes.

10% of the total

galaxy light, and has a quite flat luminosity

profile. Interestingly, one also sees that, indeed, bars have very boxy

shapes.

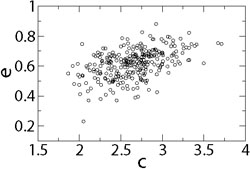

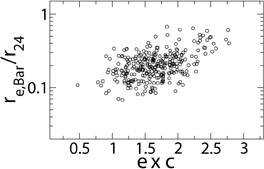

These data also reveal interesting

correlations. The left-hand panel in Fig. 3 shows a

correlation between bar ellipticity and boxyness, i.e. more eccentric

bars are also more boxy. Both quantities contribute to the strength of

the bar. Thus, the product of both,

× c,

can be used as a

measure of bar strength. The right-hand panel shows that the effective

radius of the bar, normalised by r24, is correlated

with

× c,

can be used as a

measure of bar strength. The right-hand panel shows that the effective

radius of the bar, normalised by r24, is correlated

with  ×

c (see also

[65]).

Thus, longer bars are thinner and

stronger, as expected from the theoretical models mentioned above. The

left-hand panel in Fig. 4 shows that the length of

the bar, normalised by r24, is correlated with the

bulge-to-total ratio of the galaxy. Considering these results and the

theoretical expectations together, they indicate that bars grow longer,

thinner and stronger with age, as a result of angular momentum exchange,

and that bars have had more time to evolve in galaxies with more massive

bulges. In fact, the right-hand panel in Fig. 4

shows that the normalised effective radii of bars and bulges are

correlated (see also

[6]).

Hence, the growth of bars and bulges seems to be somehow connected. Through

different paths, these conclusions are also reached by others

[87,

27].

A more thorough analysis of these data will be published elsewhere.

×

c (see also

[65]).

Thus, longer bars are thinner and

stronger, as expected from the theoretical models mentioned above. The

left-hand panel in Fig. 4 shows that the length of

the bar, normalised by r24, is correlated with the

bulge-to-total ratio of the galaxy. Considering these results and the

theoretical expectations together, they indicate that bars grow longer,

thinner and stronger with age, as a result of angular momentum exchange,

and that bars have had more time to evolve in galaxies with more massive

bulges. In fact, the right-hand panel in Fig. 4

shows that the normalised effective radii of bars and bulges are

correlated (see also

[6]).

Hence, the growth of bars and bulges seems to be somehow connected. Through

different paths, these conclusions are also reached by others

[87,

27].

A more thorough analysis of these data will be published elsewhere.

|

|

Figure 3. Left: correlation between the bar ellipticity and boxyness. Right: correlation between the effective radius of the bar normalised by r24 and the product of the bar ellipticity and boxyness. |

|