5.1. Ionizing Continuum Radiation

AGNs, at least when unobscured, reveal themselves as pointlike nuclear

sources with power-law spectra at optical and UV wavelengths, typically

described by a continuum flux density

f

, with

, with

-0.5 (e.g.,

Vanden Berk et al. 2001).

In unbeamed sources, this featureless continuum traces the

low-frequency tail of the "big blue bump"

(Shields 1978;

Malkan & Sargent 1982),

which supplies the bulk of the ionizing photons. This

feature is extremely difficult to detect in LLAGNs, both because the big

blue bump is weak or absent (Section 5.8) and because

the sources are

exceedingly faint. The optical nuclei of LINERs can have

MB

-0.5 (e.g.,

Vanden Berk et al. 2001).

In unbeamed sources, this featureless continuum traces the

low-frequency tail of the "big blue bump"

(Shields 1978;

Malkan & Sargent 1982),

which supplies the bulk of the ionizing photons. This

feature is extremely difficult to detect in LLAGNs, both because the big

blue bump is weak or absent (Section 5.8) and because

the sources are

exceedingly faint. The optical nuclei of LINERs can have

MB  -10 mag

(Ho 2004b),

at least 104 times fainter than their

(usually bulge-dominated) hosts (MB

-10 mag

(Ho 2004b),

at least 104 times fainter than their

(usually bulge-dominated) hosts (MB

M*

M*

-20 mag). To overcome

this contrast problem, searches for nuclear point sources in the optical

and near-IR have relied on HST images (e.g.,

Chiaberge, Capetti &

Celotti 1999;

Quillen et al. 2001;

Verdoes Kleijn et al. 2002;

Chiaberge, Capetti &

Macchetto 2005;

Balmaverde & Capetti 2006;

González-Martín et

al. 2006).

But resolution alone is not enough. Given the extreme

faintness of the nucleus, the intrinsic cuspiness of the underlying

bulge profile, complexities of the point-spread function, and the often

irregular background marred by circumnuclear dust features, one must pay

very close attention to how the measurements are made. Simple

aperture photometry or searching for central excess emission can yield

very misleading results. The most robust technique to extract faint

nuclei in the presence of these complications employs two-dimensional,

multi-component fitting

(Ho & Peng 2001;

Ravindranath et al. 2001;

Peng et al. 2002).

Using this method, nuclear sources with optical

magnitudes as faint as ~ 20 have been measured, with limits down to ~

22-23 mag possible for nearby galaxies. Due to the computational

requirements of two-dimensional fitting, however, not many LLAGNs have

yet been analyzed in this manner, and fewer still have enough

photometric points to define even a crude spectral slope.

-20 mag). To overcome

this contrast problem, searches for nuclear point sources in the optical

and near-IR have relied on HST images (e.g.,

Chiaberge, Capetti &

Celotti 1999;

Quillen et al. 2001;

Verdoes Kleijn et al. 2002;

Chiaberge, Capetti &

Macchetto 2005;

Balmaverde & Capetti 2006;

González-Martín et

al. 2006).

But resolution alone is not enough. Given the extreme

faintness of the nucleus, the intrinsic cuspiness of the underlying

bulge profile, complexities of the point-spread function, and the often

irregular background marred by circumnuclear dust features, one must pay

very close attention to how the measurements are made. Simple

aperture photometry or searching for central excess emission can yield

very misleading results. The most robust technique to extract faint

nuclei in the presence of these complications employs two-dimensional,

multi-component fitting

(Ho & Peng 2001;

Ravindranath et al. 2001;

Peng et al. 2002).

Using this method, nuclear sources with optical

magnitudes as faint as ~ 20 have been measured, with limits down to ~

22-23 mag possible for nearby galaxies. Due to the computational

requirements of two-dimensional fitting, however, not many LLAGNs have

yet been analyzed in this manner, and fewer still have enough

photometric points to define even a crude spectral slope.

In a few cases, the optical featureless continuum has been detected

spectroscopically. From the ground, this was only possible for a couple of

the brightest sources. The stellar features of NGC 7213

(Halpern & Filippenko

1984)

and Pictor A

(Carswell et al. 1984;

Filippenko 1985)

show dilution by a featureless continuum, which can be described

approximately by a power law with a spectral index of

-1.5. The

nuclear continuum is much more readily seen in small-aperture spectra that

help to reject the bulge starlight. HST spectra have isolated the

optical continuum in several LINERs

(Ho, Filippenko & Sargent

1996;

Nicholson et al. 1998;

Ho et al. 2000;

Shields et al. 2000;

Barth et al. 2001a;

Sabra et al. 2003),

although in most objects it remains too faint to be detected

spectroscopically

(Sarzi et al. 2005).

In all well-studied cases, the optical continuum is quite steep, with

-1.5. The

nuclear continuum is much more readily seen in small-aperture spectra that

help to reject the bulge starlight. HST spectra have isolated the

optical continuum in several LINERs

(Ho, Filippenko & Sargent

1996;

Nicholson et al. 1998;

Ho et al. 2000;

Shields et al. 2000;

Barth et al. 2001a;

Sabra et al. 2003),

although in most objects it remains too faint to be detected

spectroscopically

(Sarzi et al. 2005).

In all well-studied cases, the optical continuum is quite steep, with

-1 to -2. This range

in spectral slopes is consistent with the broad-band optical

(Verdoes Kleijn et al. 2002)

and optical-UV colors

(Chiaberge et al. 2002)

of the cores frequently detected in the LINER nuclei of FR I radio galaxies.

-1 to -2. This range

in spectral slopes is consistent with the broad-band optical

(Verdoes Kleijn et al. 2002)

and optical-UV colors

(Chiaberge et al. 2002)

of the cores frequently detected in the LINER nuclei of FR I radio galaxies.

The predominantly old population of present-day bulges ensures that the stellar contamination largely disappears in the UV, especially at high resolution. A number of attempts have been made to detect UV emission in LINERs using IUE, but most of these efforts yielded ambiguous results (see review in Filippenko 1996), and real progress had to await the HST. Two dedicated HST UV (~ 2300 Å) imaging studies have been completed. Using the pre-COSTAR FOC, Maoz et al. (1996) surveyed a complete sample of 110 large, nearby galaxies, and among the subset with spectral classifications from Palomar, Maoz et al. (1995) discovered that ~25% of the LINERs show an unresolved UV core. Barth et al. (1998) found similar statistics in a more targeted WFPC2 study. They also made the suggestion, later confirmed by Pogge et al. (2000), that dust obscuration is probably the main culprit for the nondetection of UV emission in the majority of LINERs. The implication is that UV emission is significantly more common in LINERs than indicated by the detection rates. In some type 2 objects (e.g., NGC 4569 and NGC 6500), the UV emission is spatially extended and presumably not related to the nuclear source. Second-epoch UV observations with the ACS/HRC revealed that nearly all of the UV-bright sources exhibit long-term variability (Maoz et al. 2005), an important result that helps assuage fears that the UV emission might arise mainly from young stars (Maoz et al. 1998). Importantly, both type 1 and type 2 LINERs vary. UV variability has also been discovered serendipitously in a few other sources (Renzini et al. 1995; O'Connell et al. 2005).

AGNs, no matter how weak, are almost never silent in the radio. Barring chance superposition with a supernova remnant, the presence of a compact radio core is therefore a good AGN indicator. Because of the expected faintness of the nuclei, however, any search for core emission must be conducted at high sensitivity, and arcsecond-scale angular resolution or better is generally needed to isolate the nucleus from the surrounding host, which emits copious diffuse synchrotron radiation. In practice, this requires an interferometer such as the VLA.

The prevalence of weak AGNs in nearby early-type galaxies has been

established from the VLA radio continuum studies of

Sadler, Jenkins & Kotanyi

(1989)

and Wrobel & Heeschen

(1991),

whose 5 GHz

surveys with

5" report a high

incidence (~ 30 - 40%) of

radio cores in complete, optical flux-limited samples of elliptical and

S0 galaxies. Interestingly, the radio detection rate is similar to the

detection rate of optical emission lines

(Figure 4), and the optical

counterparts of the radio cores are mostly classified as LINERs

(Phillips et al. 1986;

Ho 1999a).

Conversely,

Heckman (1980b)

showed that LINERs tend to be associated with compact radio sources. The

radio powers are quite modest, generally in the range of

1019 - 1021 W Hz-1 at 5 GHz. When

available, the spectral indices tend to be relatively flat (e.g.,

Wrobel 1991;

Slee et al. 1994).

With the exception of a handful of well-known

radio galaxies with extended jets

(Wrobel 1991),

most of the radio emission is centrally concentrated.

5" report a high

incidence (~ 30 - 40%) of

radio cores in complete, optical flux-limited samples of elliptical and

S0 galaxies. Interestingly, the radio detection rate is similar to the

detection rate of optical emission lines

(Figure 4), and the optical

counterparts of the radio cores are mostly classified as LINERs

(Phillips et al. 1986;

Ho 1999a).

Conversely,

Heckman (1980b)

showed that LINERs tend to be associated with compact radio sources. The

radio powers are quite modest, generally in the range of

1019 - 1021 W Hz-1 at 5 GHz. When

available, the spectral indices tend to be relatively flat (e.g.,

Wrobel 1991;

Slee et al. 1994).

With the exception of a handful of well-known

radio galaxies with extended jets

(Wrobel 1991),

most of the radio emission is centrally concentrated.

No comparable radio survey has been done for spiral galaxies. Over the

last few years, however, a number of studies, mostly using the VLA, have

systematically targeted sizable subsets of the Palomar galaxies, to the

point that by now effectively the entire Palomar AGN sample has been

surveyed at arcsecond

(

0.15" - 2.5") resolution

(Filho, Barthel & Ho

2000,

2002a,

2006;

Nagar et al. 2000,

2002;

Ho & Ulvestad 2001;

Filho et al. 2004;

Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

2005;

Krips et al. 2007).

Because the sensitivity, resolution, and observing

frequency varied from study to study, each concentrating on different

subclasses of objects, it is nontrivial to combine the literature

results. The only survey that samples a significant fraction of the

three LLAGN classes at a uniform sensitivity and resolution is that by

Nagar et al. (2000,

2002;

Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

2005),

which was conducted at 15 GHz and

0.15" - 2.5") resolution

(Filho, Barthel & Ho

2000,

2002a,

2006;

Nagar et al. 2000,

2002;

Ho & Ulvestad 2001;

Filho et al. 2004;

Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

2005;

Krips et al. 2007).

Because the sensitivity, resolution, and observing

frequency varied from study to study, each concentrating on different

subclasses of objects, it is nontrivial to combine the literature

results. The only survey that samples a significant fraction of the

three LLAGN classes at a uniform sensitivity and resolution is that by

Nagar et al. (2000,

2002;

Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

2005),

which was conducted at 15 GHz and

=

0.15". The main drawback is that the sensitivity

of this survey (rms

=

0.15". The main drawback is that the sensitivity

of this survey (rms  0.2 mJy) is rather modest, and mJy-level sources can be missed if they

possess relatively steep spectra. Despite these limitations, Nagar et

al. detected a compact core, to a high level of completeness, in 44% of

the LINERs. Importantly, to the same level of completeness, the

Seyferts exhibit a very similar detection rate (47%). LINER 2s have a

lower detection rate than LINER 1s (38% versus 63%; see

Table 1), but

the same pattern is reflected almost exactly within the Seyfert

population (detection rate 30% for type 2s versus 72% for type

1s). Transition objects, on the other hand, clearly differ, showing a

markedly lower detection rate of only 16%, consistent with the 8.4 GHz

survey of Filho, Barthel & Ho

(2000,

2002a,

2006),

where the detection rate is ~ 25%. The statistical differences in the

Hubble type distributions of the three AGN classes

(Ho, Filippenko & Sargent

2003)

slightly complicate the interpretation of these results. To the

extent that radio power shows a mild dependence on bulge strength or BH

mass

(Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

2005;

see Ho 2002a),

the detection rates, strictly speaking, should be renormalized to

account for the

differences in morphological types among the three classes. This effect,

however, will not qualitatively change the central conclusion: if a

compact radio core guarantees AGN pedigree, then LINERs, of either type

1 or type 2, are just as AGN-like as Seyferts, whereas a significant

fraction of transition objects (roughly half) may be unrelated to AGNs.

0.2 mJy) is rather modest, and mJy-level sources can be missed if they

possess relatively steep spectra. Despite these limitations, Nagar et

al. detected a compact core, to a high level of completeness, in 44% of

the LINERs. Importantly, to the same level of completeness, the

Seyferts exhibit a very similar detection rate (47%). LINER 2s have a

lower detection rate than LINER 1s (38% versus 63%; see

Table 1), but

the same pattern is reflected almost exactly within the Seyfert

population (detection rate 30% for type 2s versus 72% for type

1s). Transition objects, on the other hand, clearly differ, showing a

markedly lower detection rate of only 16%, consistent with the 8.4 GHz

survey of Filho, Barthel & Ho

(2000,

2002a,

2006),

where the detection rate is ~ 25%. The statistical differences in the

Hubble type distributions of the three AGN classes

(Ho, Filippenko & Sargent

2003)

slightly complicate the interpretation of these results. To the

extent that radio power shows a mild dependence on bulge strength or BH

mass

(Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

2005;

see Ho 2002a),

the detection rates, strictly speaking, should be renormalized to

account for the

differences in morphological types among the three classes. This effect,

however, will not qualitatively change the central conclusion: if a

compact radio core guarantees AGN pedigree, then LINERs, of either type

1 or type 2, are just as AGN-like as Seyferts, whereas a significant

fraction of transition objects (roughly half) may be unrelated to AGNs.

| Spectral | LH |

LX | Prad | Lbol/LEdd | LX/LH |

log Ro | log RX | fb | fr | fx |

| Class | (ergs s-1) | (ergs s-1) | (W Hz-1) | (%) | (%) | (%) | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) |

| S1 | 1.9×1040 | 1.4×1041 | 8.5×1020 | 1.1×10-3 | 7.3 | 0.7 | -3.8 | 52 | 72 | 100 |

| S2 | 1.7×1039 | 1.3×1039 | 8.5×1019 | 5.9×10-6 | 0.75 | 0.4 | -3.3 | … | 30 | 86 |

| L1 | 3.7×1039 | 8.8×1039 | 2.6×1020 | 1.0×10-5 | 4.6 | 1.3 | -2.9 | 23 | 63 | 95 |

| L2 | 0.5×1039 | 1.2×1039 | 4.7×1019 | 4.8×10-6 | 1.6 | 0.8 | -2.9 | … | 38 | 74 |

| T | 0.7×1039 | 0.5×1039 | 2.4×1019 | 1.2×10-6 | 0.41 | 0.4 | -2.8 | 3 | 16 | 74 |

NOTE.- Column (1) Spectral class. (2)

Extinction-corrected luminosity of the H |

||||||||||

The detection rates from the Nagar et al. survey can be viewed as firm

lower limits. At

= 1"

and rms = 0.04 mJy at 1.4 and 5 GHz, for example, the detection rate for

the Palomar Seyferts rises to 75%

(Ho & Ulvestad 2001).

Although no lower frequency survey of LINERs has been completed so far

(apart from the lower resolution studies of

Sadler, Jenkins, &

Kotanyi 1989

and

Wrobel & Heeschen 1991

confined to early-type galaxies), the preliminary study by

Van Dyk & Ho (1998)

of 29 LINERs at 5 and 3.6 GHz

(

= 1"

and rms = 0.04 mJy at 1.4 and 5 GHz, for example, the detection rate for

the Palomar Seyferts rises to 75%

(Ho & Ulvestad 2001).

Although no lower frequency survey of LINERs has been completed so far

(apart from the lower resolution studies of

Sadler, Jenkins, &

Kotanyi 1989

and

Wrobel & Heeschen 1991

confined to early-type galaxies), the preliminary study by

Van Dyk & Ho (1998)

of 29 LINERs at 5 and 3.6 GHz

(

= 0.5"; rms = 0.05-0.1

mJy) yielded a

detection rate of over 80%, again suggesting that LINERs and Seyferts

have a comparably high incidence of radio cores.

= 0.5"; rms = 0.05-0.1

mJy) yielded a

detection rate of over 80%, again suggesting that LINERs and Seyferts

have a comparably high incidence of radio cores.

Importantly, a sizable, flux-limit subset of the 15 GHz detections has

been reobserved with the Very Long Baseline Array at 5 GHz, and

essentially all of them have been detected at milliarcsecond

resolution

(Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

2005).

The high brightness

temperatures ( 106 - 1011 K) leaves no doubt that the radio cores

are nonthermal and genuinely associated with AGN activity.

106 - 1011 K) leaves no doubt that the radio cores

are nonthermal and genuinely associated with AGN activity.

Where multifrequency data exist, their spectra tend to be flat or even

mildly inverted (

-0.2 to +0.2;

Ho et al. 1999b;

Falcke et al. 2000;

Nagar et al. 2000;

Nagar, Wilson & Falcke

2001;

Ulvestad & Ho 2001b;

Anderson, Ulvestad & Ho

2004;

Doi et al. 2005;

Krips et al. 2007),

seemingly more optically thick than

Seyferts (median

-0.2 to +0.2;

Ho et al. 1999b;

Falcke et al. 2000;

Nagar et al. 2000;

Nagar, Wilson & Falcke

2001;

Ulvestad & Ho 2001b;

Anderson, Ulvestad & Ho

2004;

Doi et al. 2005;

Krips et al. 2007),

seemingly more optically thick than

Seyferts (median  = -0.4;

Ulvestad & Ho 2001a),

and variability on timescales of months is common

(Nagar et al. 2002;

Anderson & Ulvestad 2005).

Both of these characteristics suggest that the radio emission in LINERs is

mainly confined to a compact core or base of a jet. Seyfert galaxies

contain radio cores as well, but they are often accompanied by linear,

jetlike features resolved on arcsecond scales (e.g.,

Ulvestad & Wilson 1989;

Kukula et al. 1995;

Ho & Ulvestad 2001;

Gallimore et al. 2006).

This extended component appears to be less prevalent in

LINERs, although a definitive comparison must await a survey matched in

resolution, sensitivity, and wavelength with that performed for the

Seyferts

(Ho & Ulvestad 2001).

Higher resolution images on

milliarcsecond scales do resolve elongated structures akin to

subparsec-scale jets, but most of the power is concentrated in a

compact, high-brightness temperature core

(Bietenholz, Bartel & Rupen

2000;

Falcke et al. 2000;

Ulvestad & Ho 2001b;

Filho, Barthel & Ho

2002b;

Anderson, Ulvestad & Ho

2004;

Filho et al. 2004;

Krips et al. 2007).

The comprehensive summary presented in

Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

(2005)

indicates that the incidence of milliarcsecond-scale

radio cores is similar for LINERs and Seyferts, but that subparsec-scale

jets occur more frequently in LINERs.

= -0.4;

Ulvestad & Ho 2001a),

and variability on timescales of months is common

(Nagar et al. 2002;

Anderson & Ulvestad 2005).

Both of these characteristics suggest that the radio emission in LINERs is

mainly confined to a compact core or base of a jet. Seyfert galaxies

contain radio cores as well, but they are often accompanied by linear,

jetlike features resolved on arcsecond scales (e.g.,

Ulvestad & Wilson 1989;

Kukula et al. 1995;

Ho & Ulvestad 2001;

Gallimore et al. 2006).

This extended component appears to be less prevalent in

LINERs, although a definitive comparison must await a survey matched in

resolution, sensitivity, and wavelength with that performed for the

Seyferts

(Ho & Ulvestad 2001).

Higher resolution images on

milliarcsecond scales do resolve elongated structures akin to

subparsec-scale jets, but most of the power is concentrated in a

compact, high-brightness temperature core

(Bietenholz, Bartel & Rupen

2000;

Falcke et al. 2000;

Ulvestad & Ho 2001b;

Filho, Barthel & Ho

2002b;

Anderson, Ulvestad & Ho

2004;

Filho et al. 2004;

Krips et al. 2007).

The comprehensive summary presented in

Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

(2005)

indicates that the incidence of milliarcsecond-scale

radio cores is similar for LINERs and Seyferts, but that subparsec-scale

jets occur more frequently in LINERs.

X-ray observations provide another very effective tool to isolate LLAGNs and to diagnose their physical properties. Ultra-faint LLAGNs can be identified where none was previously known in the optical (e.g., Loewenstein et al. 2001; Ho, Terashima & Ulvestad 2003; Fabbiano et al. 2004; Pellegrini et al. 2007; Wrobel, Terashima & Ho 2008). Here, too, sensitivity and resolution are critical, as the central regions of galaxies contain a plethora of discrete nonnuclear sources, often suffused with a diffuse thermal plasma. Chandra, whose ACIS camera delivers ~ 0.5" images, is the instrument of choice, although in some instances even data at ~ 5" resolution (e.g., ROSAT HRI) can still provide meaningful constraints, especially if accompanied by spectral information (e.g., XMM-Newton).

As in the radio, no truly unbiased high-resolution X-ray survey has yet been performed of an optical flux-limited sample of nearby galaxies. The closest attempt was made by Roberts & Warwick (2000), who searched for X-ray nuclear sources in 83 Palomar galaxies (~ 20% of the total sample) having archival ROSAT HRI data. This subset is probably not unbiased, but it does encapsulate all the nuclear spectral classes in the Palomar survey. In total, X-ray cores were detected in 54% of the sample, with Seyferts and LINERs (including transition objects) both showing a higher detection rate (~ 70%) than absorption (30%) or H II nuclei (40%). The high detection rate among the optically classified LLAGNs agrees well with other ROSAT studies of Palomar sources (Koratkar et al. 1995; Komossa, Böhringer & Huchra 1999; Halderson et al. 2001; Roberts, Schurch & Warwick 2001), but the nonnegligible detection rate among the inactive members suggests that a significant fraction of the "core" flux may be nonnuclear emission [X-ray binaries (XRBs) and diffuse gas] insufficiently resolved by ROSAT.

Observations with Chandra (e.g., Ho et al. 2001; Eracleous et al. 2002) confirm the suspicion that earlier X-ray studies may have suffered from confusion with extranuclear sources (Figure 5). Importantly, the sharp resolution and low background noise of ACIS enable faint point sources to be detected with brief (few ks) exposures. This makes feasible, for the first time, X-ray surveys of large samples of galaxies selected at non-X-ray wavelengths. In a snapshot survey of a distance-limited sample of Palomar LLAGNs, Ho et al. (2001) find that ~ 75% of LINERs, both type 1 and type 2, contain X-ray cores, some as faint as ~ 1038 ergs s-1 in the 2-10 keV band. Terashima & Wilson (2003b) report an even higher detection rate (100%) for a sample of LINERs chosen for having a flat-spectrum radio core. To date, roughly 50% of the entire Palomar sample, among them 40% of the AGNs, have been observed by Chandra. This rich archival resource has been the basis of a number of recent investigations focused on quantifying the AGN content of LINERs, chief among them Satyapal, Sambruna & Dudik (2004), Dudik et al. (2005), Pellegrini (2005), Satyapal et al. (2005), Flohic et al. (2006), and González-Martín et al. (2006). A common conclusion that can be distilled from these studies is that the incidence of X-ray cores among LINERs is quite high, ranging from ~ 50% to 70%, down to luminosity limits of ~ 1038 ergs s-1. The incidence of X-ray cores in LINERs is somewhat lower than, but still compares favorably to, that found in Palomar Seyferts (~ 90%), the vast majority of which now have suitable X-ray observations, as summarized in Cappi et al. (2006) and Panessa et al. (2006). While the impact of selection biases cannot be assessed easily, they are probably not very severe because most of the observations were not originally intended to study LINERs, nor were they targeting famous X-ray sources.

It is of interest to ask whether the incidence of X-ray cores in LINERs

depends on the presence of broad

H emission. The

moderate-resolution ROSAT/HRI studies of

Roberts & Warwick (2000)

and Halderson et al. (2001)

showed roughly comparable detection rates for type 1 and type 2 LINERs,

suggesting that the two classes are intrinsically similar and that

obscuration plays a minor role in differentiating them. On the other

hand, detailed X-ray spectral analysis has raised the suspicion that

LINER 2s may be a highly heterogeneous class, with the bulk of the X-ray

emission possibly arising from stellar processes. An important caveat is

that these studies were based on large-beam observations, mostly using

ASCA

(Terashima, Ho & Ptak

2000;

Terashima et al. 2000a,

2002;

Roberts, Schurch & Warwick

2001)

and the rest using BeppoSAX

(Georgantopoulos et al. 2002;

Pellegrini et al. 2002).

A clearer, more consistent picture emerges from the recent Chandra

work cited above. Although the individual samples remain small, most

Chandra surveys detect LINER 2s with roughly similar frequency as

LINER 1s, ~ 50%-60%. To gain a more comprehensive census, I have

assembled Chandra measurements for all Palomar LINERs from the

literature, along with unpublished material for a significant number of

additional objects in public archives, which were analyzed following

Ho et al. (2001).

Although clearly heterogeneous and incomplete, the final

collection of 64 LINERs (20 type 1, 44 type 2) does constitute 70% of

the entire Palomar sample. The detection rate among all LINERs is 86%,

broken down into 95% for LINER 1s and 74% for LINER 2s. For

completeness, note that a similar exercise for 36 transition objects

(55% of the parent sample) yields a detection rate of 74%, identical to

that of LINER 2s and only marginally lower than that of Seyfert 2s (86%;

Table 1).

emission. The

moderate-resolution ROSAT/HRI studies of

Roberts & Warwick (2000)

and Halderson et al. (2001)

showed roughly comparable detection rates for type 1 and type 2 LINERs,

suggesting that the two classes are intrinsically similar and that

obscuration plays a minor role in differentiating them. On the other

hand, detailed X-ray spectral analysis has raised the suspicion that

LINER 2s may be a highly heterogeneous class, with the bulk of the X-ray

emission possibly arising from stellar processes. An important caveat is

that these studies were based on large-beam observations, mostly using

ASCA

(Terashima, Ho & Ptak

2000;

Terashima et al. 2000a,

2002;

Roberts, Schurch & Warwick

2001)

and the rest using BeppoSAX

(Georgantopoulos et al. 2002;

Pellegrini et al. 2002).

A clearer, more consistent picture emerges from the recent Chandra

work cited above. Although the individual samples remain small, most

Chandra surveys detect LINER 2s with roughly similar frequency as

LINER 1s, ~ 50%-60%. To gain a more comprehensive census, I have

assembled Chandra measurements for all Palomar LINERs from the

literature, along with unpublished material for a significant number of

additional objects in public archives, which were analyzed following

Ho et al. (2001).

Although clearly heterogeneous and incomplete, the final

collection of 64 LINERs (20 type 1, 44 type 2) does constitute 70% of

the entire Palomar sample. The detection rate among all LINERs is 86%,

broken down into 95% for LINER 1s and 74% for LINER 2s. For

completeness, note that a similar exercise for 36 transition objects

(55% of the parent sample) yields a detection rate of 74%, identical to

that of LINER 2s and only marginally lower than that of Seyfert 2s (86%;

Table 1).

The X-ray spectral properties of LLAGNs, particularly LINERs, have most

thoroughly been investigated using ASCA

(Yaqoob et al. 1995;

Ishisaki et al. 1996;

Iyomoto et al. 1996,

1997,

1998a,

1998b;

Ptak et al. 1996,

1999;

Terashima et al. 1998a,

1998b,

2000a,

2000b,

2002;

Ho et al. 1999a;

Terashima, Ho & Ptak

2000;

Roberts, Schurch & Warwick

2001),

with important contributions from BeppoSAX

(Pellegrini et al. 2000a,

2000b,

2002;

Iyomoto et al. 2001;

Georgantopoulos et al. 2002;

Ptak et al. 2004).

A seminal study on M81 was done using BBXRT

(Petre et al. 1993).

Although the nuclear component was not

spatially isolated because of the poor angular resolution of these

telescopes, they had sufficient effective area to yield good photon

statistics over the energy range ~ 0.5-10 keV to spectrally

isolate the hard, power-law AGN signal. The most salient properties are

the following. (1) Over the region ~ 0.5-10 keV, the continuum can be

fit with a power law with an energy index of

-0.4 to -1.2. Although

this range overlaps with that seen in more luminous sources, the typical

value of ~ -0.8 in LLAGNs may be marginally flatter than in Seyfert 1s

(<

-0.4 to -1.2. Although

this range overlaps with that seen in more luminous sources, the typical

value of ~ -0.8 in LLAGNs may be marginally flatter than in Seyfert 1s

(< > =

-0.87 ± 0.22;

Nandra et al. 1997b)

or radio-quiet quasars

(<

> =

-0.87 ± 0.22;

Nandra et al. 1997b)

or radio-quiet quasars

(< > =

-0.93 ± 0.22;

Reeves & Turner 2000),

perhaps being more in line with radio-loud quasars

(<

> =

-0.93 ± 0.22;

Reeves & Turner 2000),

perhaps being more in line with radio-loud quasars

(<  > = -0.6

± 0.16;

Reeves & Turner 2000).

(2) With a few notable exceptions (e.g., M51:

Fukazawa et al. 2001,

Terashima & Wilson 2003a;

NGC 1052:

Weaver et al. 1999,

Guainazzi et al. 2000;

NGC 4258:

Makishima et al. 1994,

Fiore et al. 2001;

NGC 4261:

Matsumoto et al. 2001),

the power-law component shows very little

intrinsic absorption. This trend conflicts with the tendency for the

degree of obscuration to increase with decreasing luminosity (e.g.,

Lawrence & Elvis 1982).

(3) Signatures of X-ray reprocessing by

material from an optically thick accretion disk, in the form of Fe

K

> = -0.6

± 0.16;

Reeves & Turner 2000).

(2) With a few notable exceptions (e.g., M51:

Fukazawa et al. 2001,

Terashima & Wilson 2003a;

NGC 1052:

Weaver et al. 1999,

Guainazzi et al. 2000;

NGC 4258:

Makishima et al. 1994,

Fiore et al. 2001;

NGC 4261:

Matsumoto et al. 2001),

the power-law component shows very little

intrinsic absorption. This trend conflicts with the tendency for the

degree of obscuration to increase with decreasing luminosity (e.g.,

Lawrence & Elvis 1982).

(3) Signatures of X-ray reprocessing by

material from an optically thick accretion disk, in the form of Fe

K emission or Compton

reflection

(Lightman & White 1988;

George & Fabian 1991),

are weak or absent; the weakness of the Fe

K

emission or Compton

reflection

(Lightman & White 1988;

George & Fabian 1991),

are weak or absent; the weakness of the Fe

K line in LLAGNs runs

counter to the inverse correlation between iron line strength and

luminosity observed in higher luminosity AGNs

(Nandra et al. 1997b).

(4) In the few

cases where Fe K

line in LLAGNs runs

counter to the inverse correlation between iron line strength and

luminosity observed in higher luminosity AGNs

(Nandra et al. 1997b).

(4) In the few

cases where Fe K emission has been detected, it is always narrow. (5) Apart from the hard

power law, most objects require an extra soft component at energies

emission has been detected, it is always narrow. (5) Apart from the hard

power law, most objects require an extra soft component at energies

2 keV that can be fit

by a thermal plasma model with a temperature of kT

2 keV that can be fit

by a thermal plasma model with a temperature of kT

0.4-0.8 keV and

near-solar abundances. (6) Contrary to the trend established for

luminous sources

(Nandra et al. 1997a),

short-term, large-amplitude X-ray variability is rare in LLAGNs

(Ptak et al. 1998).

0.4-0.8 keV and

near-solar abundances. (6) Contrary to the trend established for

luminous sources

(Nandra et al. 1997a),

short-term, large-amplitude X-ray variability is rare in LLAGNs

(Ptak et al. 1998).

More recent observations with Chandra and XMM-Newton have

refined, but not qualitatively altered, the above results. Where

detailed spectral analysis is possible (e.g.,

Böhringer et al. 2001;

Kim & Fabbiano 2003;

Pellegrini et al. 2003a;

Terashima & Wilson 2003b;

Filho et al. 2004;

Page et al. 2004;

Starling et al. 2005;

Flohic et al. 2006;

González-Martín et

al. 2006;

Soria et al. 2006),

the hard power-law component (except in objects

previously known to be heavily absorbed) continues to be relatively

unabsorbed, even among many type 2 sources, and to show little signs of

reflection. No convincing case of a relativistic Fe

K line has yet surfaced

in an LLAGN. The marginally broad iron lines discovered with ASCA in

M81

(Ishisaki et al. 1996)

and NGC 4579

(Terashima et al. 1998a)

has now been resolved into multiple components

(Dewangan et al. 2004;

Page et al. 2004;

Young et al. 2007),

none of which can be associated with a

canonical disk. At the same time, the equivalent width limits for even

the narrow component have become impressively low (e.g.,

Ptak et al. 2004).

Interestingly, a soft thermal component is still required in

many objects (Section 5.4), but there is no evidence

for blackbody-like soft excess emission commonly seen in Seyferts and

quasars (e.g.,

Turner & Pounds 1989;

Inoue, Terashima & Ho

2007).

line has yet surfaced

in an LLAGN. The marginally broad iron lines discovered with ASCA in

M81

(Ishisaki et al. 1996)

and NGC 4579

(Terashima et al. 1998a)

has now been resolved into multiple components

(Dewangan et al. 2004;

Page et al. 2004;

Young et al. 2007),

none of which can be associated with a

canonical disk. At the same time, the equivalent width limits for even

the narrow component have become impressively low (e.g.,

Ptak et al. 2004).

Interestingly, a soft thermal component is still required in

many objects (Section 5.4), but there is no evidence

for blackbody-like soft excess emission commonly seen in Seyferts and

quasars (e.g.,

Turner & Pounds 1989;

Inoue, Terashima & Ho

2007).

5.4. Circumnuclear Thermal Plasma

Early X-ray observations of LLAGNs using ASCA have consistently

revealed the presence of a diffuse, thermal component, typically with a

temperature of kT

0.5 keV

(Ptak et al. 1999;

Terashima et al. 2002).

The uniform analysis of ROSAT data by

Halderson et al. (2001)

concluded that ~ 80% of the Palomar sources contain an extended

component. However, without better resolution, it was impossible to know

the extent of confusion with point sources, how much of the gas is truly

associated with the nuclear region of the galaxy, or the density and

temperature profile of the gas.

0.5 keV

(Ptak et al. 1999;

Terashima et al. 2002).

The uniform analysis of ROSAT data by

Halderson et al. (2001)

concluded that ~ 80% of the Palomar sources contain an extended

component. However, without better resolution, it was impossible to know

the extent of confusion with point sources, how much of the gas is truly

associated with the nuclear region of the galaxy, or the density and

temperature profile of the gas.

Our view of the diffuse component in the nuclear region has been

dramatically sharpened with Chandra and XMM-Newton. Not

only has the near ubiquity of diffuse gas been confirmed in many nearby

galaxies

(Ho et al. 2001;

Eracleous et al. 2002;

Terashima & Wilson 2003b;

Pellegrini 2005;

Rinn, Sambruna & Gliozzi

2005;

Cappi et al. 2006;

González-Martín et

al. 2006;

Soria et al. 2006),

including our own

(Muno et al. 2004)

and our close neighbor M31

(Garcia et al. 2005),

but quantitative, statistical properties of the gas are now becoming

available. In the comprehensive investigation of 19 LINERs by

Flohic et al. (2006),

the diffuse emission, detected in 70% of the

sample, is concentrated within the central few hundred pc. With an

average 0.5-2 keV luminosity of ~ 1038 ergs s-1,

it accounts for more than half of the total central luminosity in most

cases. The average spectrum is similar to that seen in normal galaxies:

it can be described by a thermal plasma with kT = 0.5 keV plus a

power-law component with  = -0.3 to -0.5. I will return to the nature of the hard

component in Section 6.5. What is the origin

of the thermal plasma? Given what we know about the stellar populations

(Section 4.2), a

starburst origin, as suggested by

González-Martín et

al. (2006),

seems improbable. In normal elliptical galaxies, the

X-ray-emitting gas represents the repository of thermalized

stellar ejecta generated from mass loss from evolved stars and Type Ia

supernovae (e.g.,

Awaki et al. 1994).

There is no reason not to adopt

the same picture to explain the hot plasma in LINERs and other

LLAGNs. High-resolution X-ray spectroscopy of the highly ionized gas

around the nucleus of M81

(Page et al. 2003;

Young et al. 2007)

and NGC 7213

(Starling et al. 2005)

reveals that the plasma is collisionally

ionized. Starling et al. note that this may be a property unique to

LINERs, as thermal gas in luminous Seyferts is usually photoionized

rather than collisionally ionized (e.g.,

Kinkhabwala et al. 2002).

= -0.3 to -0.5. I will return to the nature of the hard

component in Section 6.5. What is the origin

of the thermal plasma? Given what we know about the stellar populations

(Section 4.2), a

starburst origin, as suggested by

González-Martín et

al. (2006),

seems improbable. In normal elliptical galaxies, the

X-ray-emitting gas represents the repository of thermalized

stellar ejecta generated from mass loss from evolved stars and Type Ia

supernovae (e.g.,

Awaki et al. 1994).

There is no reason not to adopt

the same picture to explain the hot plasma in LINERs and other

LLAGNs. High-resolution X-ray spectroscopy of the highly ionized gas

around the nucleus of M81

(Page et al. 2003;

Young et al. 2007)

and NGC 7213

(Starling et al. 2005)

reveals that the plasma is collisionally

ionized. Starling et al. note that this may be a property unique to

LINERs, as thermal gas in luminous Seyferts is usually photoionized

rather than collisionally ionized (e.g.,

Kinkhabwala et al. 2002).

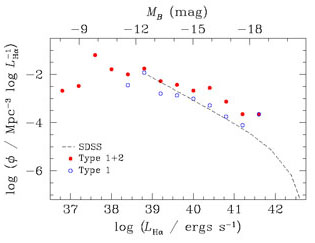

Luminous, unobscured AGNs distinguish themselves unambiguously by their

characteristic broad permitted lines. The detection of broad

H emission in ~ 25% of

LINERs

(Ho et al. 1997e)

thus constitutes strong evidence in favor of

the AGN interpretation of these sources. LINERs, like Seyferts, come in

two flavors - some have a visible BLR (type 1), and others do not

(type 2). The broad component becomes progressively more difficult to

detect in ground-based spectra for permitted lines weaker than

H

emission in ~ 25% of

LINERs

(Ho et al. 1997e)

thus constitutes strong evidence in favor of

the AGN interpretation of these sources. LINERs, like Seyferts, come in

two flavors - some have a visible BLR (type 1), and others do not

(type 2). The broad component becomes progressively more difficult to

detect in ground-based spectra for permitted lines weaker than

H . However, HST

spectra

of LINERs, when available, show broad higher-order Balmer lines as well

as UV lines such as Ly

. However, HST

spectra

of LINERs, when available, show broad higher-order Balmer lines as well

as UV lines such as Ly ,

C IV

,

C IV  1549, Mg II

1549, Mg II

2800, and Fe II multiplets

(Barth et al. 1996;

Ho, Filippenko & Sargent

1996).

A subset of LINERs contain broad lines with

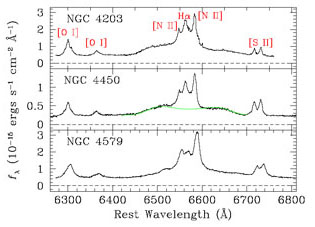

double-peaked profiles (Figure 6),

analogous to those seen in a minority of radio galaxies

(Eracleous & Halpern

1994),

where they are often interpreted as a kinematic signature of a

relativistic accretion disk

(Chen & Halpern 1989).

Most of the nearby cases have

been discovered serendipitously, either as a result of the broad

component being variable (NGC 1097:

Storchi-Bergmann, Baldwin &

Wilson 1993;

M81:

Bower et al. 1996;

NGC 3065:

Eracleous & Halpern 2001)

or because of the increased sensitivity to weak, broad features

afforded by small-aperture measurements made with HST (NGC 4450:

Ho et al. 2000;

NGC 4203:

Shields et al. 2000;

NGC 4579:

Barth et al. 2001a).

Double-peaked broad-line AGNs may be more common than

previously thought, especially among LLAGNs, perhaps as a consequence of

their accretion disk structure (Section 8).

2800, and Fe II multiplets

(Barth et al. 1996;

Ho, Filippenko & Sargent

1996).

A subset of LINERs contain broad lines with

double-peaked profiles (Figure 6),

analogous to those seen in a minority of radio galaxies

(Eracleous & Halpern

1994),

where they are often interpreted as a kinematic signature of a

relativistic accretion disk

(Chen & Halpern 1989).

Most of the nearby cases have

been discovered serendipitously, either as a result of the broad

component being variable (NGC 1097:

Storchi-Bergmann, Baldwin &

Wilson 1993;

M81:

Bower et al. 1996;

NGC 3065:

Eracleous & Halpern 2001)

or because of the increased sensitivity to weak, broad features

afforded by small-aperture measurements made with HST (NGC 4450:

Ho et al. 2000;

NGC 4203:

Shields et al. 2000;

NGC 4579:

Barth et al. 2001a).

Double-peaked broad-line AGNs may be more common than

previously thought, especially among LLAGNs, perhaps as a consequence of

their accretion disk structure (Section 8).

|

Figure 6. LINERs with broad, double-peaked

H |

A pressing question, however, is: What fraction of the more numerous

LINER 2s are AGNs? By analogy with the Seyfert 2 class, do LINER 2s

contain a hidden LINER 1 nucleus? At first sight, it might seem that

there is no a priori reason why the orientation-dependent

unification model, which has enjoyed much success in the context of

Seyfert galaxies, should not apply equally to LINERs. If we suppose that

the ratio of LINER 2s to LINER 1s is similar to the ratio of Seyfert 2s

to Seyfert 1s - 1.6:1 in the Palomar survey - we can reasonably

surmise that the AGN fraction in LINERs may be as high as ~ 60%. That at

least some LINERs do indeed contain a hidden BLR was demonstrated

by the deep Keck spectropolarimetric observations of Barth, Filippenko

& Moran

(1999a,

1999b).

In a survey of 14 LLAGNs, mostly LINERs, these authors detected broad

H emission in three

objects (~ 20%) polarized at a level of 1%-3%. Interestingly, all three

objects are elliptical galaxies with double-sided radio jets. NGC 315 and NGC 1052 technically qualify as type 1.9 LINERs

(Ho et al. 1997e),

whereas NGC 4261 is a LINER

2. Although the sample is small, these observations prove two important

points: (1) the weak broad

H

emission in three

objects (~ 20%) polarized at a level of 1%-3%. Interestingly, all three

objects are elliptical galaxies with double-sided radio jets. NGC 315 and NGC 1052 technically qualify as type 1.9 LINERs

(Ho et al. 1997e),

whereas NGC 4261 is a LINER

2. Although the sample is small, these observations prove two important

points: (1) the weak broad

H features detected in

direct light is not always scattered emission

(Antonucci 1993),

since polarized emission was not detected in

several other LINER 1.9s included in Barth, Filippenko & Moran's

survey; (2) an obscured nucleus does lurk in some LINER 2s.

features detected in

direct light is not always scattered emission

(Antonucci 1993),

since polarized emission was not detected in

several other LINER 1.9s included in Barth, Filippenko & Moran's

survey; (2) an obscured nucleus does lurk in some LINER 2s.

At the same time, other bright LINER 2s have resisted detection by spectropolarimetry. As in the case of Seyferts (Tran 2001), however, the nondetection of polarized broad lines does not necessarily imply that there is no hidden BLR. Nevertheless, the BLR in some type 2 AGNs, especially LINERs but also Seyferts, may be intrinsically absent, not obscured. In the case of some Seyferts, mostly weak sources, the evidence comes from low absorbing X-ray column densities (Bassani et al. 1999; Pappa et al. 2001; Panessa & Bassani 2002; Gliozzi et al. 2004; Cappi et al. 2006; Gliozzi, Sambruna & Foschini 2007; Bianchi et al. 2008; but see Ghosh et al. 2007) as well as optical variability (Hawkins 2004). LINERs, as a class, very much conform to this picture. As discussed further below, LINERs of either type generally show very little sign of absorbing or reprocessing material, and UV variability is common. A few exceptions exist (e.g., NGC 1052: Guainazzi et al. 2000; NGC 4261: Sambruna et al. 2003, Zezas et al. 2005), but, interestingly, these are precisely the very ones for which Barth, Filippenko, & Moran discovered hidden BLRs. NGC 4258, also highly absorbed in the X-rays (Fiore et al. 2001), shows polarized narrow lines rather than broad lines (Barth et al. 1999).

An excellent of a LINER with a naked type 2 nucleus is the

Sombrero galaxy. Although clearly an AGN, it shows

no trace of a broad-line component, neither in direct light

(Ho et al. 1997e),

not even when very well isolated with a small HST aperture

(Nicholson et al. 1998),

nor in polarized light

(Barth, Filippenko & Moran

1999b).

Its Balmer

decrement indicates little reddening to the NLR. For all practical

purposes, the continuum emission from the nucleus looks unobscured. It

is detected as a variable UV source

(Maoz et al. 1995,

2005)

and in the soft and hard X-rays

(Nicholson et al. 1998;

Ho et al. 2001).

The X-ray spectrum is only very mildly absorbed

(Nicholson et al. 1998;

Pellegrini et al. 2002,

2003a;

Terashima et al. 2002),

with no signs of

Fe K emission expected

from reprocessed material, consistent with the modest mid-IR emission

reported by

Bendo et al. (2006).

In short, there is no sign of anything being hidden or much doing the

hiding. So where is the BLR? It is just not there.

emission expected

from reprocessed material, consistent with the modest mid-IR emission

reported by

Bendo et al. (2006).

In short, there is no sign of anything being hidden or much doing the

hiding. So where is the BLR? It is just not there.

The lack of a BLR in very low-luminosity sources may be related to a

physical upper limit in the broad-line width

(Laor 2003).

If LLAGNs obey the same BLR-luminosity relation as in higher luminosity

systems, their BLR velocity depends on the BH mass and luminosity. At a

limiting bolometric luminosity of Lbol

1041.8

(MBH / 108

M

1041.8

(MBH / 108

M )2 ergs s-1,

)2 ergs s-1,

v

v

25,000 km

s-1, above which clouds may not

survive due to excessive shear or tidal forces. Alternatively, if BLR

clouds arise from condensations in a radiation-driven, outflowing wind

(Murray & Chiang 1997),

a viewpoint now much espoused, then it is

reasonable to expect that very low-luminosity sources would be incapable

of generating a wind, and hence of sustaining a BLR. For example, the

clumpy torus model of

Elitzur & Shlosman (2006)

predicts that the

BLR can no longer be sustained for Lbol

25,000 km

s-1, above which clouds may not

survive due to excessive shear or tidal forces. Alternatively, if BLR

clouds arise from condensations in a radiation-driven, outflowing wind

(Murray & Chiang 1997),

a viewpoint now much espoused, then it is

reasonable to expect that very low-luminosity sources would be incapable

of generating a wind, and hence of sustaining a BLR. For example, the

clumpy torus model of

Elitzur & Shlosman (2006)

predicts that the

BLR can no longer be sustained for Lbol

1042 ergs

s-1. In the scenario of

Nicastro (2000),

the BLR originates

from a disk outflow formed at the transition radius between regions

dominated by gas and radiation pressure. As this radius shrinks with

decreasing Lbol / LEdd,

where LEdd = 1.3 × 1038

(MBH /

M

1042 ergs

s-1. In the scenario of

Nicastro (2000),

the BLR originates

from a disk outflow formed at the transition radius between regions

dominated by gas and radiation pressure. As this radius shrinks with

decreasing Lbol / LEdd,

where LEdd = 1.3 × 1038

(MBH /

M ) ergs

s-1, the BLR is expected to disappear for

Lbol / LEdd

) ergs

s-1, the BLR is expected to disappear for

Lbol / LEdd

10-3. The

apparent correlation between BLR line width and

Lbol / LEdd

qualitatively supports this picture

(Xu & Cao 2007).

Although the

existing data are sparse, they indicate that LINERs generally lack UV

resonance absorption features indicative of nuclear outflows

(Shields et al. 2002).

The models by Elitzur & Shlosman and Nicastro are

probably correct in spirit but not in detail, because many of the

Palomar LLAGNs plainly violate their proposed thresholds

(Section 5.10).

10-3. The

apparent correlation between BLR line width and

Lbol / LEdd

qualitatively supports this picture

(Xu & Cao 2007).

Although the

existing data are sparse, they indicate that LINERs generally lack UV

resonance absorption features indicative of nuclear outflows

(Shields et al. 2002).

The models by Elitzur & Shlosman and Nicastro are

probably correct in spirit but not in detail, because many of the

Palomar LLAGNs plainly violate their proposed thresholds

(Section 5.10).

Nonetheless, the statistics within the Palomar survey already provide

tentative support to the thesis that the BLR vanishes at the lowest

luminosities or Eddington ratios. Which of the two is the controlling

variable is still difficult to say. For both Seyferts and LINERs, type 1

sources are almost a factor of 10 more luminous than type 2 sources in

terms of their median total

H luminosity

(Table 1). (The statistical differences between

type 1 and type 2 sources cannot be ascribed to sensitivity differences

in the detectability of broad

H

luminosity

(Table 1). (The statistical differences between

type 1 and type 2 sources cannot be ascribed to sensitivity differences

in the detectability of broad

H emission. Type 1

objects do have stronger line emission

compared to the type 2s, but on average their narrow

H

emission. Type 1

objects do have stronger line emission

compared to the type 2s, but on average their narrow

H flux and equivalent width

are only ~ 50% higher, and the two types overlap

significantly. Moreover, as noted in

Section 3.4, the broad

H

flux and equivalent width

are only ~ 50% higher, and the two types overlap

significantly. Moreover, as noted in

Section 3.4, the broad

H detection rates turn

out to be quite robust even in light of the much higher sensitivity

afforded by

HST.) The differences persist after normalizing by the Eddington

luminosities: adopting a bolometric correction of Lbol

detection rates turn

out to be quite robust even in light of the much higher sensitivity

afforded by

HST.) The differences persist after normalizing by the Eddington

luminosities: adopting a bolometric correction of Lbol

16

LX,

Lbol / LEdd = 1.1 × 10-3

and 5.9 × 10-6 for Seyfert 1s and Seyfert 2s,

respectively, whereas the corresponding values for LINER 1s and LINER 2s

are 1.0 × 10-5 and 4.8 × 10-6. Two

caveats are in order. First, while most of the type 1 sources have X-ray

data, only 60% of the LINER 2s and 70% of the Seyfert 2s do. Second, the

X-ray luminosities, which pertain to the 2-10 keV band, have been

corrected for intrinsic absorption whenever possible, but many sources

are too faint for spectral analysis. The lower X-ray luminosities for

the type 2 sources must be partly due to absorption, but considering the

generally low absorbing columns, particularly among the LINERs

(Georgantopoulous et

al. 2002;

Terashima et al. 2002),

it is unclear if

absorption alone can erase the statistical difference between the two

types. The tendency for Seyfert 2s to have lower Eddington ratios than

Seyfert 1s has previously been noted, for the Palomar sample

(Panessa et al. 2006)

and others

(Middleton, Done & Schurch

2008).

16

LX,

Lbol / LEdd = 1.1 × 10-3

and 5.9 × 10-6 for Seyfert 1s and Seyfert 2s,

respectively, whereas the corresponding values for LINER 1s and LINER 2s

are 1.0 × 10-5 and 4.8 × 10-6. Two

caveats are in order. First, while most of the type 1 sources have X-ray

data, only 60% of the LINER 2s and 70% of the Seyfert 2s do. Second, the

X-ray luminosities, which pertain to the 2-10 keV band, have been

corrected for intrinsic absorption whenever possible, but many sources

are too faint for spectral analysis. The lower X-ray luminosities for

the type 2 sources must be partly due to absorption, but considering the

generally low absorbing columns, particularly among the LINERs

(Georgantopoulous et

al. 2002;

Terashima et al. 2002),

it is unclear if

absorption alone can erase the statistical difference between the two

types. The tendency for Seyfert 2s to have lower Eddington ratios than

Seyfert 1s has previously been noted, for the Palomar sample

(Panessa et al. 2006)

and others

(Middleton, Done & Schurch

2008).

Several authors have raised the suspicion that LINER 2s may not be

accretion-powered. Large-aperture X-ray spectra of LINER 2s, like those of

LINER 1s, can be fit with a soft thermal component plus a power law with

-0.7 to -1.5

(Georgantopoulos et al. 2002;

Terashima et al. 2002).

But this alone does not provide enough leverage to distinguish AGNs from

starburst galaxies, many of which look qualitatively similar over the

limited energy range covered by these observations. We cannot turn to

the iron K

-0.7 to -1.5

(Georgantopoulos et al. 2002;

Terashima et al. 2002).

But this alone does not provide enough leverage to distinguish AGNs from

starburst galaxies, many of which look qualitatively similar over the

limited energy range covered by these observations. We cannot turn to

the iron K line or variability for guidance, because LLAGNs generally exhibit neither

(Section 5.3). The hard X-ray emission in LINER 2s is

partly extended

(Terashima et al. 2000a>;

Georgantopoulos et al. 2002),

but the implications of this finding are unclear. Just because the X-ray

emission surrounding the LLAGN is morphologically complex and there is

evidence for circumnuclear star formation (e.g., NGC 4736;

Pellegrini et al. 2002)

does not necessarily imply that there is a causal connection between the

starburst and the LLAGN.

Roberts, Schurch & Warwick

(2001)

advocate a starburst connection from the observation that

LINER 2s have a mean flux ratio in the soft and hard X-ray band (~ 0.7)

similar to that found in NGC 253. This interpretation, however, conflicts

with the stellar population constraints discussed in

Section 4.2. It is also not

unique. Luminous, AGN-dominated type 1 sources themselves exhibit a tight

correlation between soft and hard X-ray luminosity, with a ratio not

dissimilar from the quoted value

(Miniutti et al. 2008).

line or variability for guidance, because LLAGNs generally exhibit neither

(Section 5.3). The hard X-ray emission in LINER 2s is

partly extended

(Terashima et al. 2000a>;

Georgantopoulos et al. 2002),

but the implications of this finding are unclear. Just because the X-ray

emission surrounding the LLAGN is morphologically complex and there is

evidence for circumnuclear star formation (e.g., NGC 4736;

Pellegrini et al. 2002)

does not necessarily imply that there is a causal connection between the

starburst and the LLAGN.

Roberts, Schurch & Warwick

(2001)

advocate a starburst connection from the observation that

LINER 2s have a mean flux ratio in the soft and hard X-ray band (~ 0.7)

similar to that found in NGC 253. This interpretation, however, conflicts

with the stellar population constraints discussed in

Section 4.2. It is also not

unique. Luminous, AGN-dominated type 1 sources themselves exhibit a tight

correlation between soft and hard X-ray luminosity, with a ratio not

dissimilar from the quoted value

(Miniutti et al. 2008).

An important clue comes from the fact that many LINER 2s have a lower

LX /

LH ratio than LINER 1s

(Ho et al. 2001).

In particular, the observed X-ray luminosity from the

nucleus, when extrapolated to the UV, does not have enough ionizing

photons to power the H

ratio than LINER 1s

(Ho et al. 2001).

In particular, the observed X-ray luminosity from the

nucleus, when extrapolated to the UV, does not have enough ionizing

photons to power the H emission

(Terashima et al. 2000a).

This implies that (1) the X-rays are

heavily absorbed, (2) nonnuclear processes power much of the optical

line emission, or (3) the ionizing SED is different than assumed. As

discussed in Section 6.4, this energy budget

discrepancy appears to be

symptomatic of all LLAGNs in general, not just LINER 2s, and most likely

results from a combination of the second and third effect. There are

some indications that the SEDs of LINER 2s indeed differ systematically

from those of LINER 1s (e.g.,

Maoz et al. 2005;

Sturm et al. 2006).

In light of the evidence given in Sections 5.3,

< ahref="#5.6">5.6, I consider the first

solution to be no longer tenable. One can point to objects such as

NGC 4261

(Zezas et al. 2005)

as examples of LINER 2s with strong obscuration, but such cases are rare.

emission

(Terashima et al. 2000a).

This implies that (1) the X-rays are

heavily absorbed, (2) nonnuclear processes power much of the optical

line emission, or (3) the ionizing SED is different than assumed. As

discussed in Section 6.4, this energy budget

discrepancy appears to be

symptomatic of all LLAGNs in general, not just LINER 2s, and most likely

results from a combination of the second and third effect. There are

some indications that the SEDs of LINER 2s indeed differ systematically

from those of LINER 1s (e.g.,

Maoz et al. 2005;

Sturm et al. 2006).

In light of the evidence given in Sections 5.3,

< ahref="#5.6">5.6, I consider the first

solution to be no longer tenable. One can point to objects such as

NGC 4261

(Zezas et al. 2005)

as examples of LINER 2s with strong obscuration, but such cases are rare.

From the point of view of BH demographics, the most pressing issue is what fraction of the LINER 2s should be included in the AGN tally. Some cases are beyond dispute (M84, M87, Sombrero). What about the rest? The strongest argument that the majority of LINER 2s are AGN-related comes from the detection frequency of radio (Section 5.2) and X-ray (Section 5.3) cores, which is roughly 60% of that of LINER 1s. On the other hand, the detection rate of Seyfert 2s are similarly lower compared to Seyfert 1s, most likely reflecting the overall reduction of nuclear emission across all bands in type 2 LLAGNs as a consequence of their lower accretion rates. In summary, the AGN fraction among LINER 2s is at least 60%, and possibly as high as 100%.

In line with the absence of a BLR discussed above and using very much the

same set of evidence, a convincing case can be made that the torus also

disappears at very low luminosities. In a large fraction of nearby LINERs,

the low absorbing column densities and weak or undetected Fe

K emission

(Section 5.3) strongly indicate that we have a

direct, unobstructed view of the nucleus.

Ghosh et al. (2007)

warn that absorbing columns can be underestimated

in the presence of extended soft emission, especially when working with

spectra of low signal-to-noise ratio. While this bias no doubt enters at

some level, cases like the Sombrero (Section 5.3)

cannot be so readily dismissed. By analogy with situation in luminous

AGNs (e.g.,

Inoue, Terashima & Ho

2007;

Nandra et al. 2007),

type 1 LLAGNs, if they possess tori, should also show

strong, narrow fluorescent Fe

K

emission

(Section 5.3) strongly indicate that we have a

direct, unobstructed view of the nucleus.

Ghosh et al. (2007)

warn that absorbing columns can be underestimated

in the presence of extended soft emission, especially when working with

spectra of low signal-to-noise ratio. While this bias no doubt enters at

some level, cases like the Sombrero (Section 5.3)

cannot be so readily dismissed. By analogy with situation in luminous

AGNs (e.g.,

Inoue, Terashima & Ho

2007;

Nandra et al. 2007),

type 1 LLAGNs, if they possess tori, should also show

strong, narrow fluorescent Fe

K emission. This

expectation is not borne out by observations. NGC 3998, which has excellent X-ray data, offers

perhaps the most dramatic example. Apart from showing no signs

whatsoever for intrinsic photoelectric absorption, it also possesses one

of the tightest upper limits to date on Fe

K

emission. This

expectation is not borne out by observations. NGC 3998, which has excellent X-ray data, offers

perhaps the most dramatic example. Apart from showing no signs

whatsoever for intrinsic photoelectric absorption, it also possesses one

of the tightest upper limits to date on Fe

K emission: EW < 25 eV

(Ptak et al. 2004).

Our sight line to the nucleus is as clean as a whistle.

Satyapal, Sambruna & Dudik

(2004)

claim that many LINERs have obscured nuclei, but

this conclusion is based on IR-bright, dusty objects chosen from

Carrillo et al. (1999);

as I have discussed in Section 3.2, I regard

these objects not only as

biased, but also confusing with respect to their nuclear properties.

emission: EW < 25 eV

(Ptak et al. 2004).

Our sight line to the nucleus is as clean as a whistle.

Satyapal, Sambruna & Dudik

(2004)

claim that many LINERs have obscured nuclei, but

this conclusion is based on IR-bright, dusty objects chosen from

Carrillo et al. (1999);

as I have discussed in Section 3.2, I regard

these objects not only as

biased, but also confusing with respect to their nuclear properties.

Palomar Seyferts, whose luminosities and Eddington ratios are about an

order of magnitude higher than those of LINERs

(Section 5.10), show

markedly larger absorbing column densities and stronger Fe

K lines. In an

XMM-Newton study of a distance-limited sample of 27 Palomar

Seyferts,

Cappi et al. (2006)

detect strong Fe

K

lines. In an

XMM-Newton study of a distance-limited sample of 27 Palomar

Seyferts,

Cappi et al. (2006)

detect strong Fe

K emission in over half of

objects. The distribution of absorbing columns is nearly continuous,

from NH

emission in over half of

objects. The distribution of absorbing columns is nearly continuous,

from NH

1020 to

1025 cm-2,

with 30%-50% of the type 2 sources being Compton-thick

(Panessa et al. 2006).

This seems consistent with the tendency for Seyferts to be

more gas-rich than LINERs, to the extent that this is reflected in their

higher NLR densities

(Ho, Filippenko & Sargent

2003).

1020 to

1025 cm-2,

with 30%-50% of the type 2 sources being Compton-thick

(Panessa et al. 2006).

This seems consistent with the tendency for Seyferts to be

more gas-rich than LINERs, to the extent that this is reflected in their

higher NLR densities

(Ho, Filippenko & Sargent

2003).

The trend of increasing absorption with increasing luminosity or

Eddington ratio observed in Palomar LLAGNs has an interesting parallel

among radio galaxies. A substantial body of recent work indicates that

the nuclei of FR I sources, most of which are, in fact, LINERs, are

largely unobscured (e.g.,

Chiaberge, Capetti &

Celotti 1999;

Donato, Sambruna & Gliozzi

2004;

Balmaverde & Capetti

2006).

In contrast, FR II systems, especially those with broad or high-excitation

lines (analogs of Seyferts), show clear signs of absorption and Fe

K emission

(Evans et al. 2006).

emission

(Evans et al. 2006).

Even if we are fooled by the X-ray observations, substantial absorption must result in strong thermal reemission of "waste heat" in the IR. While sources such as Cen A provide a clear reminder that every rule has its exception (Whysong & Antonucci 2004), the existing data do suggest that, as a class, FR I radio galaxies tend to be weak mid-IR or far-IR sources (Haas et al. 2004; Müller et al. 2004). The same holds for more nearby LINERs. Their SEDs do show a pronounced mid-IR peak (Section 5.8), but as I will argue later, it is due to emission from the accretion flow rather than from dust reemission.

5.7. Narrow-line Region Kinematics

The kinematics of the NLR are complex. At the smallest scales probed by HST, Verdoes Kleijn, van der Marel & Noel-Storr (2006) find that the velocity widths of the ionized gas in the LINER nuclei of early-type galaxies can be modeled as unresolved rotation of a thin disk in the gravitational potential of the central BH. The subset of objects with FR I radio morphologies, on the other hand, exhibit line broadening in excess of that expected from purely gravitational motions; these authors surmise that the super-virial motions may be related to an extra source of energy injection by the radio jet. Walsh et al. (2008) use multiple-slit STIS observations to map the kinematics of the inner ~ 100 pc of the NLR in a sample of 14 LLAGNs, mostly LINERs. Consistent with earlier findings (Ho et al. 2002; Atkinson et al. 2005), the velocity fields are generally quite disorganized, rarely showing clean signatures of dynamically cold disks undergoing circular rotation. Nevertheless, two interesting trends can be discerned. The emission line widths tend to be largest within the sphere of influence of the BH, progressively decreasing toward large radii to values that roughly match the stellar velocity dispersion of the bulge. The luminous members of the sample, on the other hand, show more chaotic kinematics, as evidenced by large velocity splittings and asymmetric line profiles, reminiscent of the pattern observed by Rice et al. (2006) in their sample of Seyfert galaxies. Walsh et al. suggest that above a certain luminosity threshold - one that perhaps coincides with the LINER/Seyfert division - AGN outflows and radio jets strongly perturb the kinematics of the NLR.

A large fraction (~ 90%) of the Palomar LLAGNs have robust measurements

of integrated

[N II]  6583 line

widths, which enable a crude

assessment of the dynamical state of the NLR and its relation to the

bulge. Consistent with what has been established for more powerful

systems

(Nelson & Whittle 1996;

Greene & Ho 2005a),

the kinematics of the ionized gas are dominated by random motions that, to

first order, trace the gravitational potential of the stars in the

bulge. Among the objects with available central stellar velocity

dispersions,

6583 line

widths, which enable a crude

assessment of the dynamical state of the NLR and its relation to the

bulge. Consistent with what has been established for more powerful

systems

(Nelson & Whittle 1996;

Greene & Ho 2005a),

the kinematics of the ionized gas are dominated by random motions that, to

first order, trace the gravitational potential of the stars in the

bulge. Among the objects with available central stellar velocity

dispersions,

NLR /

NLR /

*

*

0.7-0.8 for the weakest

sources

(LH

0.7-0.8 for the weakest

sources

(LH

1038 ergs s-1), systematically rising to

1038 ergs s-1), systematically rising to

NLR

/

NLR

/  *

*

1.2 in the more luminous

members

(LH

1.2 in the more luminous

members

(LH

1041.5 ergs s-1). L.C. Ho (in preparation)

speculates that the central AGN injects a source of dynamical heating of

nongravitational origin to the NLR, either in the form of radiation

pressure from the central continuum or mechanical interaction from radio

jets. Given the empirical correlation between optical line luminosity

and radio power (e.g.,

Ho & Peng 2001;

Ulvestad & Ho 2001a;

Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

2005),

and the near ubiquity of compact radio

sources, it is a priori difficult to determine which of these two

sources acts as the primary driver. The tendency for extended radio

emission to be more prevalent in Seyferts (Section 5.2)

suggests that jets may be more important.

1041.5 ergs s-1). L.C. Ho (in preparation)

speculates that the central AGN injects a source of dynamical heating of

nongravitational origin to the NLR, either in the form of radiation

pressure from the central continuum or mechanical interaction from radio

jets. Given the empirical correlation between optical line luminosity

and radio power (e.g.,

Ho & Peng 2001;

Ulvestad & Ho 2001a;

Nagar, Falcke & Wilson

2005),

and the near ubiquity of compact radio

sources, it is a priori difficult to determine which of these two

sources acts as the primary driver. The tendency for extended radio

emission to be more prevalent in Seyferts (Section 5.2)

suggests that jets may be more important.

5.8. Spectral Energy Distribution

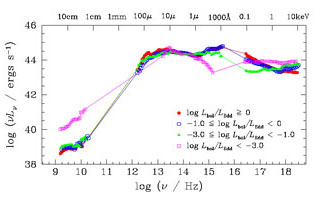

The broad-band SED provides one of the most fundamental probes of the physical processes in AGNs. Both thermal and nonthermal emission contribute to the broad-band spectrum of luminous AGNs such as quasars and classical Seyfert galaxies. In objects whose intrinsic spectrum has not been modified severely by relativistic beaming or absorption, the SED can be separated into several distinctive components (e.g., Elvis et al. 1994): radio synchrotron emission from a jet, which may be strong ("radio-loud") or weak ("radio-quiet"); an IR excess, now generally considered to be predominantly thermal reradiation by dust grains; a prominent optical to UV "big blue bump," usually interpreted to be pseudo-blackbody emission from an optically thick, geometrically thin accretion disk (Shields 1978; Malkan & Sargent 1982); a soft X-ray excess, whose origin is still highly controversial (Done et al. 2007; Miniutti et al. 2008); and an underlying power law, which is most conspicuous at hard X-ray energies but is thought to extend down to IR wavelengths, that can be attributed to Comptonization of softer seed photons.

Within this backdrop, there were already early indications that the SEDs

of LINERs may deviate from the canonical form.

Halpern & Filippenko

(1984)

succeeded in detecting the featureless optical continuum in

NGC 7213, and while these authors suggested that a

big blue bump may be

present in this object, they also noted that it possesses an

exceptionally high X-ray-to-optical flux ratio, although

perhaps one not inconsistent with the extrapolation of the trend of

increasing X-ray-to-optical flux ratio with decreasing

luminosity seen in luminous sources

(Zamorani et al. 1981;

Avni & Tananbaum 1982).

A more explicit suggestion that LINERs may possess a

weak UV continuum was made in the context of double-peaked broad-line

AGNs such as Arp 102B and Pictor A, whose narrow-line spectra share many

characteristics with LINERs

(Chen & Halpern 1989;

Halpern & Eracleous

1994).

The HST spectrum of Arp 102B, in fact, shows an

exceptionally steep optical-UV nonstellar continuum

(

-2.1 to -2.4;

Halpern et al. 1996).

Halpern & Eracleous

(1994)

further suggested that the

SEDs are flat in the far-IR. In an important study of M81,

Petre et al. (1993)

proposed that the relative weakness of the UV continuum

compared to the X-rays is a consequence of a change in the structure of

the central accretion flow, from a standard thin disk to an

ion-supported torus (see Section 8.3).