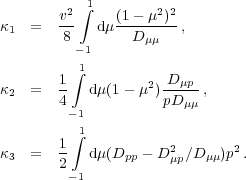

In this section we describe some of the mathematical details required for investigation of the acceleration and transport of all charged particles stochastically and by shocks, and the steps and conditions that lead to the specific kinetic equations (Eq. 10) used in this and the previous chapters.

A.1. Stochastic acceleration by turbulence

In strong magnetic fields, the gyro-radii of particles are much

smaller than the scale of the spatial variation of the field, so

that the gyro-phase averaged distribution of the particles depends

only on four variables: time, spatial coordinate z along the

field lines, the momentum p, and the pitch angle cosµ.

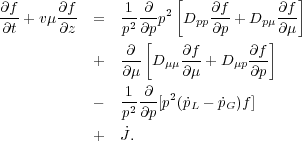

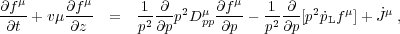

In this case, the evolution of the particle distribution,

f(t, z,

p, µ), can be described by the Fokker-Planck equation

as they undergo stochastic acceleration by interaction with plasma

turbulence (diffusion coefficients Dpp,

Dµµ and

Dpµ), direct acceleration (with rate

G), and suffer losses (with rate

G), and suffer losses (with rate

L)

due to other interactions with the plasma particles and fields:

L)

due to other interactions with the plasma particles and fields:

|

(19) |

Here

c

is the velocity of the particles and

c

is the velocity of the particles and

(t, z,

p, µ)

is a source term, which could be the background plasma or some injected

spectrum of particles. The kinetic coefficients in the Fokker-Planck

equation can be expressed through correlation functions of stochastic

electromagnetic fields (see e.g.

Melrose 1980,

Berezinskii et al. 1990,

Schlickeiser 2002).

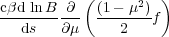

The effect of the mean magnetic field convergence or divergence can be

accounted for by adding

(t, z,

p, µ)

is a source term, which could be the background plasma or some injected

spectrum of particles. The kinetic coefficients in the Fokker-Planck

equation can be expressed through correlation functions of stochastic

electromagnetic fields (see e.g.

Melrose 1980,

Berezinskii et al. 1990,

Schlickeiser 2002).

The effect of the mean magnetic field convergence or divergence can be

accounted for by adding

|

(20) |

to the right hand side.

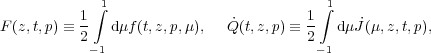

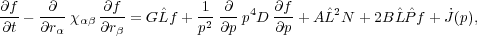

Pitch-angle isotropy: At high energies and in weakly magnetised

plasmas with Alfvén velocity

A

A

vA /

c << 1 the ratio

of the energy and pitch angle diffusion rates Dpp /

p2 Dµµ

vA /

c << 1 the ratio

of the energy and pitch angle diffusion rates Dpp /

p2 Dµµ

(

( A

/

A

/  )2 << 1, and one can use

the isotropic approximation

which leads to the diffusion-convection equation (see e.g.

Dung &

Petrosian 1994,

Kirk et

al. 1988):

)2 << 1, and one can use

the isotropic approximation

which leads to the diffusion-convection equation (see e.g.

Dung &

Petrosian 1994,

Kirk et

al. 1988):

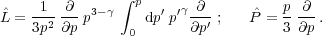

|

(21) |

|

(22) |

|

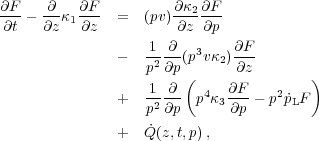

At low energies, as shown by

Pryadko & Petrosian (1997),

specially for strongly

magnetised plasmas ( << 1,

<< 1,

A

> 1), Dpp / p2 >>

Dµµ, and then stochastic acceleration is more

efficient than

acceleration by shocks (Dpp / p2

>>

A

> 1), Dpp / p2 >>

Dµµ, and then stochastic acceleration is more

efficient than

acceleration by shocks (Dpp / p2

>>  G). In this case the pitch angle

dependence may not be ignored.

G). In this case the pitch angle

dependence may not be ignored.

|

(23) |

However, Petrosian & Liu (2004) find that these dependences are in general weak and one can average over the pitch angles.

A.2. Acceleration in large scale turbulence and shocks

In an astrophysical context it often happens that the energy is released at scales much larger than the mean free path of energetic particles. If the produced large scale MHD turbulence is supersonic and superalfvénic then MHD shocks are present in the system. The particle distribution within such a system is highly intermittent. Statistical description of intermittent systems differs from the description of homogeneous systems. There are strong fluctuations of particle distribution in shock vicinities. A set of kinetic equations for the intermittent system was constructed by Bykov & Toptygin (1993), where the smooth averaged distribution obeys an integro-differential equation (due to strong shocks), and the particle distribution in the vicinity of a shock can be calculated once the averaged function was found.

The pitch-angle averaged distribution function N(r, p, t) of non-thermal particles (with energies below some hundreds of GeV range in the cluster case) averaged over an ensemble of turbulent motions and shocks satisfies the kinetic equation

|

(24) |

The source term  (t,

r, p) is determined by

injection of particles. The integro-differential operators

(t,

r, p) is determined by

injection of particles. The integro-differential operators

and

and

are given by

are given by

|

(25) |

The averaged kinetic coefficients A, B, D,

G, and

=

=

are

expressed in terms of the spectral functions that describe

correlations between large scale turbulent motions and shocks, the

particle spectra index

are

expressed in terms of the spectral functions that describe

correlations between large scale turbulent motions and shocks, the

particle spectra index

depends

on the shock ensemble properties (see

Bykov &

Toptygin 1993).

The kinetic coefficients satisfy the following renormalisation equations:

depends

on the shock ensemble properties (see

Bykov &

Toptygin 1993).

The kinetic coefficients satisfy the following renormalisation equations:

|

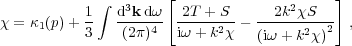

(26) |

|

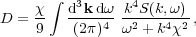

(27) |

|

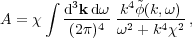

(28) |

|

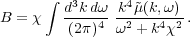

(29) |

Here G = ( 1 /

sh +

B). T(k,

sh +

B). T(k,

) and S(k,

) and S(k,

) are the

transverse and longitudinal parts of the Fourier components of the

turbulent velocity correlation tensor. Correlations between velocity

jumps on shock fronts

are described by ϕ(k,

) are the

transverse and longitudinal parts of the Fourier components of the

turbulent velocity correlation tensor. Correlations between velocity

jumps on shock fronts

are described by ϕ(k,

), while

µ(k,

), while

µ(k, )

represents shock-rarefaction correlations. The introduction of these

spectral functions is dictated by the intermittent character of a system

with shocks.

)

represents shock-rarefaction correlations. The introduction of these

spectral functions is dictated by the intermittent character of a system

with shocks.

The test particle calculations showed that the low energy branch of the particle distribution would contain a substantial fraction of the free energy of the system after a few acceleration times. Thus, to calculate the efficiency of the shock turbulence power conversion to the non-thermal particle component, as well as the particle spectra, we have to account for the backreaction of the accelerated particles on the shock turbulence. To do that, Bykov (2001) supplied the kinetic equations Eqs. 24 - 29 with the energy conservation equation for the total system including the shock turbulence and the non-thermal particles, resulting in temporal evolution of particle spectra.