The synchrotron emission is produced by the spiraling motion of relativistic electrons in a magnetic field. It is therefore the easiest and more direct way to detect magnetic fields in astrophysical sources. The total synchrotron emission from a source provides an estimate of the strength of magnetic fields while the degree of polarization is an important indicator of the field uniformity and structure.

An electron of energy

=

=

me c2 (where

me c2 (where

is the

Lorentz factor) in a magnetic field

is the

Lorentz factor) in a magnetic field

experiences a

experiences a

×

×

force that causes

it to follow a helical path

along the field lines, emitting radiation into a cone of half-angle

force that causes

it to follow a helical path

along the field lines, emitting radiation into a cone of half-angle

-1

about its instantaneous velocity. To the

observer, the radiation is essentially a continuum with a fairly

peaked spectrum concentrated near the critical frequency

-1

about its instantaneous velocity. To the

observer, the radiation is essentially a continuum with a fairly

peaked spectrum concentrated near the critical frequency

|

(1) |

The synchrotron power emitted by a relativistic electron is

|

(2) |

where  is the pitch

angle between the electron velocity and the magnetic field direction while

c1 and c2 depend only on fundamental

physical constants

is the pitch

angle between the electron velocity and the magnetic field direction while

c1 and c2 depend only on fundamental

physical constants

|

(3) |

In practical units:

|

(4)

|

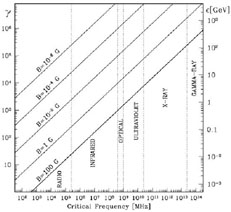

From Eq. 1, it is derived that electrons of

104 in

magnetic fields of B

104 in

magnetic fields of B

1 G produce synchrotron

radiation in the optical domain, whereas electrons of

1 G produce synchrotron

radiation in the optical domain, whereas electrons of

105 in

magnetic fields of

B

105 in

magnetic fields of

B  10 G radiate

in the X-rays (see

Fig. 1). Therefore at a given frequency, the

energy (or

Lorentz factor) of the emitting electrons depends directly on the

magnetic field strengths. The higher is the magnetic field strength,

the lower is the electron energy needed to produce emission at a given

frequency. In a magnetic field of about B

10 G radiate

in the X-rays (see

Fig. 1). Therefore at a given frequency, the

energy (or

Lorentz factor) of the emitting electrons depends directly on the

magnetic field strengths. The higher is the magnetic field strength,

the lower is the electron energy needed to produce emission at a given

frequency. In a magnetic field of about B

1 µG, a

synchrotron radiation detected for example at 100 MHz, is produced

by relativistic electrons with

1 µG, a

synchrotron radiation detected for example at 100 MHz, is produced

by relativistic electrons with

5000.

5000.

|

Figure 1. Electron Lorentz factor

|

For an homogeneous and isotropic population of electrons with a

power-law energy distribution, i.e. with the particle density between

and

and

+

d

+

d given by

given by

|

(6) |

the total intensity spectrum, in regions which are optically thin to their own radiation, varies as:

|

(7) |

where the spectral index  =

(

=

( - 1) / 2.

Below the frequency where the synchrotron emitting region becomes

optically thick, the total intensity spectrum

can be described by:

- 1) / 2.

Below the frequency where the synchrotron emitting region becomes

optically thick, the total intensity spectrum

can be described by:

|

(8) |

The synchrotron emission radiating from a population of relativistic electrons in a uniform magnetic field is linearly polarized. In the optically thin case, the degree of intrinsic linear polarization, for a homogeneous and isotropic distribution of relativistic electrons with a power-law spectrum as in Eq. 6, is:

|

(9) |

with the electric (polarization) vector perpendicular to the projection of the magnetic field onto the plane of the sky. For typical values of the particle spectral index, the intrinsic polarization degree is ~ 75 - 80%. In the optically thick case:

|

(10) |

and the electric vector is parallel to the projected magnetic field.

In practice, the polarization degree detected in radio sources is much lower than expected by the above equations. A reduction in polarization could be due to a complex magnetic field structure whose orientation varies either with depth in the source or over the angular size of the beam. For instance, if one describes the magnetic field inside an optically thin source as the superposition of two components, one uniform Bu, the other isotropic and random Br, the observed degree of polarization can be approximated by [7]:

|

(11) |

A rigorous treatment of how the degree of polarization is affected by the magnetic field configuration is presented by Sokoloff et al. [8, 9].