The temperature anisotropy at a point on the sky

( ,

,

) can be

expressed in the basis of spherical harmonics as

) can be

expressed in the basis of spherical harmonics as

|

(7) |

A cosmological model predicts the variance of the

a m coefficients

over an ensemble of universes (or an ensemble of observational

points within one universe, if the universe is ergodic). The

assumptions of rotational symmetry and Gaussianity allow

us to express this ensemble average in terms of the multipoles

C

m coefficients

over an ensemble of universes (or an ensemble of observational

points within one universe, if the universe is ergodic). The

assumptions of rotational symmetry and Gaussianity allow

us to express this ensemble average in terms of the multipoles

C as

as

|

(8) |

The predictions of a cosmological model can be expressed in terms of

C alone if

that model predicts a Gaussian distribution of density perturbations,

in which case the a

alone if

that model predicts a Gaussian distribution of density perturbations,

in which case the a m will have mean zero

and variance C

m will have mean zero

and variance C .

.

The temperature anisotropies of the CMB detected by COBE are believed to result from inhomogeneities in the distribution of matter at the epoch of recombination. Because Compton scattering is an isotropic process in the electron rest frame, any primordial anisotropies (as opposed to inhomogeneities) should have been smoothed out before decoupling. This lends credence to the interpretation of the observed anisotropies as the result of density perturbations which seeded the formation of galaxies and clusters. The discovery of temperature anisotropies by COBE provides evidence that such density inhomogeneities existed in the early universe, perhaps caused by quantum fluctuations in the scalar field of inflation or by topological defects resulting from a phase transition (see Kamionkowski & Kosowsky, 1999 for a detailed review of inflationary and defect model predictions for CMB anisotropies). Gravitational collapse of these primordial density inhomogeneities appears to have formed the large-scale structures of galaxies, clusters, and superclusters that we observe today.

On large (super-horizon) scales, the anisotropies seen in the CMB are produced by the Sachs-Wolfe effect (Sachs & Wolfe, 1967).

|

(9) |

where the first term is the net Doppler shift of the photon

due to the relative motion of emitter and observer, which

is referred to as the kinematic dipole. This dipole, first observed by

Smoot et

al. (1977),

is much larger than other CMB anisotropies and is believed to reflect the

motion of the Earth relative to the average reference frame of the CMB.

Most of this motion is due to the peculiar velocity of the

Local Group of galaxies. The second term represents the gravitational

redshift due to a difference in

gravitational potential between the site of photon emission and the

observer. The third term is called the Integrated

Sachs-Wolfe (ISW) effect and is caused by a non-zero time derivative of

the metric along the photon's path of travel due to potential decay,

gravitational waves, or non-linear structure evolution (the Rees-Sciama

effect). In a matter-dominated universe with scalar density

perturbations the integral vanishes on linear scales.

This equation gives the redshift

from emission to observation, but there is also an intrinsic

T / T

on the last-scattering surface due to the local density of photons.

For adiabatic perturbations, we have

(White & Hu,

1997)

an intrinsic

T / T

on the last-scattering surface due to the local density of photons.

For adiabatic perturbations, we have

(White & Hu,

1997)

an intrinsic

|

(10) |

Putting the observer at  = 0 (the observer's gravitational potential merely adds a constant

energy to all CMB photons) this leads to a net Sachs-Wolfe effect of

= 0 (the observer's gravitational potential merely adds a constant

energy to all CMB photons) this leads to a net Sachs-Wolfe effect of

T / T

= -

T / T

= -  / 3 which means

that overdensities lead to cold spots in the CMB.

/ 3 which means

that overdensities lead to cold spots in the CMB.

Anisotropy measurements on small angular scales (0.°1 to 1°) are expected to reveal the so-called first acoustic peak of the CMB power spectrum. This peak in the anisotropy power spectrum corresponds to the scale where acoustic oscillations of the photon-baryon fluid caused by primordial density inhomogeneities are just reaching their maximum amplitude at the surface of last scattering i.e. the sound horizon at recombination. Further acoustic peaks occur at scales that are reaching their second, third, fourth, etc. antinodes of oscillation.

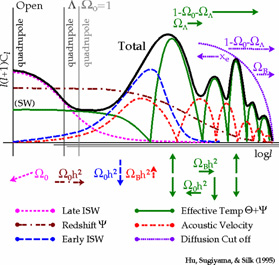

Figure 2 (from

Hu et al., 1997)

shows the dependence of the CMB anisotropy power spectrum on a number of

cosmological parameters. The acoustic oscillations in

density (light solid line) are sharp

here because they are really being plotted against spatial scales, which

are then smoothed as they are projected through the last-scattering surface

onto angular scales. The troughs in the density oscillations are filled in

by the 90-degree-out-of-phase velocity oscillations (this is a Doppler

effect but does not correspond to the net peaks, which

are best referred to as acoustic peaks rather than Doppler peaks).

The origin of this plot is at a different place for different values of

the matter density and the cosmological constant; the negative

spatial curvature of an open universe makes a given spatial scale

correspond to a smaller angular scale.

The Integrated Sachs-Wolfe (ISW) effect occurs whenever

gravitational potentials decay due to a lack of matter dominance. Hence

the early ISW effect occurs just after recombination when the density

of radiation is still considerable and serves to broaden the first

acoustic peak at scales just larger than the horizon size at

recombination. And for a present-day matter density less than critical,

there is a late ISW effect that matters on very large angular scales - it

is greater in amplitude for open universes than for lambda-dominated

because matter domination ends earlier in an open universe for the same

value of the matter density today. The late ISW effect should correlate

with large-scale structures that are otherwise detectable at z ~

1, and this allows the CMB to be cross-correlated with observations of

the X-ray background to determine

(Boughn et al.,

1998;

Kamionkowski

& Kinkhabwala, 1999;

Crittenden

& Turok, 1996;

Kamionkowski,

1996)

or with observations

of large-scale structure to determine the bias of galaxies

(Suginohara

et al., 1998).

(Boughn et al.,

1998;

Kamionkowski

& Kinkhabwala, 1999;

Crittenden

& Turok, 1996;

Kamionkowski,

1996)

or with observations

of large-scale structure to determine the bias of galaxies

(Suginohara

et al., 1998).

|

Figure 2. Dependence of CMB anisotropy power spectrum on cosmological parameters. |

For a given model, the location of the

first acoustic peak can yield information about

, the ratio of

the density of the universe to the critical density needed to stop

its expansion. For adiabatic density perturbations, the first

acoustic peak will occur at

, the ratio of

the density of the universe to the critical density needed to stop

its expansion. For adiabatic density perturbations, the first

acoustic peak will occur at

= 220

= 220

-1/2

(Kamionkowski

et al., 1994).

The ratio of

-1/2

(Kamionkowski

et al., 1994).

The ratio of  values of the

peaks is a robust test of the nature of the density perturbations; for

adiabatic perturbations these will have ratio 1:2:3:4 whereas for

isocurvature perturbations the ratio should be 1:3:5:7

(Hu & White,

1996).

A mixture of adiabatic and isocurvature

perturbations is possible, and this test should reveal it.

values of the

peaks is a robust test of the nature of the density perturbations; for

adiabatic perturbations these will have ratio 1:2:3:4 whereas for

isocurvature perturbations the ratio should be 1:3:5:7

(Hu & White,

1996).

A mixture of adiabatic and isocurvature

perturbations is possible, and this test should reveal it.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the amplitude of the

acoustic peaks depends on the baryon fraction

b,

the matter density

b,

the matter density

0, and

Hubble's constant H0 = 100h km/s/Mpc.

A precise measurement of all three acoustic peaks can reveal

the fraction of hot dark matter and even potentially the number

of neutrino species

(Dodelson et

al., 1996).

Figure 2 shows the envelope of the

CMB anisotropy damping tail on arcminute scales,

where the fluctuations are decreased due to photon diffusion

(Silk, 1967)

as well as the finite thickness of the last-scattering

surface. This damping tail is a sensitive probe

of cosmological parameters and has the potential to

break degeneracies between models which explain the larger-scale

anisotropies

(Hu & White,

1997b;

Metcalf &

Silk, 1998).

The characteristic angular scale for this damping is given by

1.8'

0, and

Hubble's constant H0 = 100h km/s/Mpc.

A precise measurement of all three acoustic peaks can reveal

the fraction of hot dark matter and even potentially the number

of neutrino species

(Dodelson et

al., 1996).

Figure 2 shows the envelope of the

CMB anisotropy damping tail on arcminute scales,

where the fluctuations are decreased due to photon diffusion

(Silk, 1967)

as well as the finite thickness of the last-scattering

surface. This damping tail is a sensitive probe

of cosmological parameters and has the potential to

break degeneracies between models which explain the larger-scale

anisotropies

(Hu & White,

1997b;

Metcalf &

Silk, 1998).

The characteristic angular scale for this damping is given by

1.8'  B-1/2

B-1/2

03/4 h-1/2

(White et al.,

1994).

03/4 h-1/2

(White et al.,

1994).

There is now a plethora of theoretical

models which predict the development of primordial

density perturbations into microwave

background anisotropies. These models differ in their explanation

of the origin of density inhomogeneities

(inflation or topological defects), the nature of the dark matter (hot,

cold, baryonic, or a mixture of the three),

the curvature of the universe

( ),

the value of the cosmological constant

(

),

the value of the cosmological constant

( ),

the value of Hubble's constant, and

the possibility of reionization which

wholly or partially erased temperature anisotropies in the CMB on

scales smaller than the horizon size. Available data does not allow

us to constrain all (or even most) of these parameters, so analyzing

current CMB anisotropy data requires

a model-independent approach. It seems

reasonable to view the mapping of the acoustic peaks as

a means of determining the nature of parameter space

before going on to fitting cosmological parameters directly.

),

the value of Hubble's constant, and

the possibility of reionization which

wholly or partially erased temperature anisotropies in the CMB on

scales smaller than the horizon size. Available data does not allow

us to constrain all (or even most) of these parameters, so analyzing

current CMB anisotropy data requires

a model-independent approach. It seems

reasonable to view the mapping of the acoustic peaks as

a means of determining the nature of parameter space

before going on to fitting cosmological parameters directly.

The possibility that post-decoupling interactions between ionized matter and the CBR have affected the anisotropies on scales smaller than those measured by COBE is of great significance for current experiments. Reionization is inevitable but its effect on anisotropies depends significantly on when it occurs (see Haimann & Knox, 1999 for a review). Early reionization leads to a larger optical depth and therefore a greater damping of the anisotropy power spectrum due to the secondary scattering of CMB photons off of the newly free electrons. For a universe with critical matter density and constant ionization fraction xe, the optical depth as a function of redshift is given by (White et al., 1994)

|

(11) |

which allows us to determine the redshift of reionization

z* at which

= 1,

= 1,

|

(12) |

where the scaling with

applies to an open

universe only. At scales smaller than the horizon size at reionization,

applies to an open

universe only. At scales smaller than the horizon size at reionization,

T / T

is reduced by the factor

e-

T / T

is reduced by the factor

e- .

.

Attempts to measure

the temperature anisotropy on angular scales of less than a degree which

correspond to the size of galaxies could have led to a surprise;

if the universe was reionized after recombination to the extent

that the CBR was significantly scattered

at redshifts less than 1100, the small-scale

primordial anisotropies would have been washed out.

To have an appreciable optical depth

for photon-matter interaction, reionization cannot have occurred

much later than a redshift of 20

(Padmanabhan,

1993).

Large-scale anisotropies such as those

seen by COBE are not expected to be affeced by reionization because they

encompass regions of the universe which were not yet in causal contact

even at the proposed time of reionization. However, the apparently high

amplitiude of degree-scale anisotropies is a strong argument against the

possibility of early (z

50) reionization.

On arc-minute scales, the

interaction of photons with reionized matter is expected to have eliminated

the primordial anisotropies and replaced them with smaller secondary

anisotropies from this new surface of last scattering (the

Ostriker-Vishniac effect and patchy reionization, see next section).

50) reionization.

On arc-minute scales, the

interaction of photons with reionized matter is expected to have eliminated

the primordial anisotropies and replaced them with smaller secondary

anisotropies from this new surface of last scattering (the

Ostriker-Vishniac effect and patchy reionization, see next section).

Secondary CMB anisotropies occur when the photons of the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation are scattered after the original last-scattering surface (see Refregier, 1999 for a review). The shape of the blackbody spectrum can be altered through inverse Compton scattering by the thermal Sunyaev-Zel'dovich (SZ) effect (Sunyaev & Zeldovich, 1972). The effective temperature of the blackbody can be shifted locally by a doppler shift from the peculiar velocity of the scattering medium (the kinetic SZ and Ostriker-Vishniac effects, Ostriker & Vishniac, 1986) as well as by passage through the changing gravitational potential caused by the collapse of nonlinear structure (the Rees-Sciama effect, Rees & Sciama, 1968) or the onset of curvature or cosmological constant domination (the Integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect). Several simulations of the impact of patchy reionization have been performed (Gruzinov & Hu, 1998; Peebles & Juszkiewicz, 1998; Aghanim et al., 1996; Knox et al., 1998). The SZ effect itself is independent of redshift, so it can yield information on clusters at much higher redshift than does X-ray emission. However, nearly all clusters are unresolved for 10' resolution so higher-redshift clusters occupy less of the beam and therefore their SZ effect is in fact dimmer. In the 4.5' channels of Planck this will no longer be true, and the SZ effect can probe cluster abundance at high redshift. An additional secondary anisotropy is that caused by gravitational lensing (see e.g. Cayon et al., 1994; Metcalf & Silk, 1997; Martinez-Gonzalez et al., 1997; Cayon et al., 1993). Gravitational lensing imprints slight non-Gaussianity in the CMB from which it might be possible to determine the matter power spectrum (Zaldarriaga & Seljak, 1998; Seljak & Zaldarriaga, 1998).

3.4. Polarization Anisotropies

Polarization of the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation (Zaldarriaga & Seljak, 1997; Kamionkowski et al., 1997; Kosowsky, 1994) arises due to local quadrupole anisotropies at each point on the surface of last scattering (see Hu & White, 1997a for a review). Scalar (density) perturbations generate curl-free (electric mode) polarization only, but tensor (gravitational wave) perturbations can generate divergence-free (magnetic mode) polarization. Hence the polarization of the CMB is a potentially useful probe of the level of gravitational waves in the early universe (Kamionkowski & Kosowsky, 1998; Seljak & Zaldarriaga, 1997), especially since current indications are that the large-scale primary anisotropies seen by COBE do not contain a measurable fraction of tensor contributions (Gawiser & Silk, 1998). A thorough review of gravity waves and CMB polarization is given by Kamionkowski & Kosowsky (1999).

3.5. Gaussianity of the CMB anisotropies

The processes turning density inhomogeneities into CMB anisotropies

are linear, so cosmological models that predict gaussian primordial

density inhomogeneities also predict a gaussian distribution of

CMB temperature fluctuations. Several techniques have been developed

to test COBE and future datasets for deviations from gaussianity (e.g.

Ferreira et

al., 1997;

Kogut et al.,

1996b;

Ferreira &

Magueijo, 1997).

Most tests have proven negative, but a few claims of non-gaussianity

have been made.

Gaztañaga et

al. (1998)

found a very marginal indication

of non-gaussianity in the spread of results for degree-scale

CMB anisotropy observations being greater than the expected sample

variances.

Ferreira et

al. (1998)

have claimed a detection of non-gaussianity

at multipole  = 16 using a

bispectrum statistic, and

Pando et al. (1998)

find a non-gaussian wavelet coefficient correlation

on roughly 15° scales in the North Galactic hemisphere. Both

of these methods produce results consistent with gaussianity, however, if

a particular area of several pixels is eliminated from the dataset

(Bromley &

Tegmark, 1999).

A true sky signal should be larger than several

pixels so instrument noise is the most likely source of the

non-gaussianity. A different area appears to cause each detection, giving

evidence that the COBE dataset had non-gaussian instrument noise in at

least two areas of the sky.

= 16 using a

bispectrum statistic, and

Pando et al. (1998)

find a non-gaussian wavelet coefficient correlation

on roughly 15° scales in the North Galactic hemisphere. Both

of these methods produce results consistent with gaussianity, however, if

a particular area of several pixels is eliminated from the dataset

(Bromley &

Tegmark, 1999).

A true sky signal should be larger than several

pixels so instrument noise is the most likely source of the

non-gaussianity. A different area appears to cause each detection, giving

evidence that the COBE dataset had non-gaussian instrument noise in at

least two areas of the sky.

Of particular concern in measuring CMB anisotropies is the issue of foreground contamination. Foregrounds which can affect CMB observations include galactic radio emission (synchrotron and free-free), galactic infrared emission (dust), extragalactic radio sources (primarily elliptical galaxies, active galactic nuclei, and quasars), extragalactic infrared sources (mostly dusty spirals and high-redshift starburst galaxies), and the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect from hot gas in galaxy clusters. The COBE team has gone to great lengths to analyze their data for possible foreground contamination and routinely eliminates everything within about 30° of the galactic plane.

An instrument with large resolution such as COBE is most sensitive to the diffuse foreground emission of our Galaxy, but small-scale anisotropy experiments need to worry about extragalactic sources as well. Because foreground and CMB anisotropies are assumed to be uncorrelated, they should add in quadrature, leading to an increase in the measurement of CMB anisotropy power. Most CMB instruments, however, can identify foregrounds by their spectral signature across multiple frequencies or their display of the beam response characteristic of a point source. This leads to an attempt at foreground subtraction, which can cause an underestimate of CMB anisotropy if some true signal is subtracted along with the foreground. Because they are now becoming critical, extragalactic foregrounds have been studied in detail (Gawiser et al., 1998; Gawiser & Smoot, 1997; Toffolatti et al., 1998; Refregier et al., 1998; Sokasian et al., 1998). The Wavelength-Oriented Microwave Background Analysis Team (WOMBAT, see Gawiser et al., 1998; Jaffe et al., 1999) has made Galactic and extragalactic foreground predictions and full-sky simulations of realistic CMB skymaps containing foreground contamination available to the public (see http://astro.berkeley.edu/wombat). One of these CMB simulations is shown in Figure 3. Tegmark et al. (1999) used a Fisher matrix analysis to show that simultaneously estimating foreground model parameters and cosmological parameters can lead to a factor of a few degradation in the precision with which the cosmological parameters can be determined by CMB anisotropy observations, so foreground prediction and subtraction is likely to be an important aspect of future CMB data analysis.

Foreground contamination may turn out to be a serious problem for measurements of CMB polarization anisotropy. While free-free emission is unpolarized, synchrotron radiation displays a linear polarization determined by the coherence of the magnetic field along the line of sight; this is typically on the order of 10% for Galactic synchrotron and between 5 and 10% for flat-spectrum radio sources. The CMB is expected to show a large-angular scale linear polarization of about 10%, so the prospects for detecting polarization anisotropy are no worse than for temperature anisotropy although higher sensitivity is required. However, the small-angular scale electric mode of linear polarization which is a probe of several cosmological parameters and the magnetic mode that serves as a probe of tensor perturbations are expected to have much lower amplitude and may be swamped by foreground polarization. Thermal and spinning dust grain emission can also be polarized. It may turn out that dust emission is the only significant source of circularly polarized microwave photons since the CMB cannot have circular polarization.