Based on the above picture, we can broadly classify the gas in a superwind into two categories. The first is the ambient interstellar medium, and the second is the the volume-filling energetic fluid created by the thermalization of the starburst's stellar eject. The thermal and kinetic energy of this fluid is the "piston" that drives the outflow and dominates its energy budget. The observed manifestations of superwinds arise when the primary wind fluid interacts hydrodynamically with relatively dense ambient interstellar gas.

This has long been known to apply to the optical emission-line gas. In the case of superbubbles, the limb-brightened morphology and the classic "Doppler ellipses" seen in long-slit spectroscopy of dwarf starburst galaxies (e.g. Meurer et al. 1992; Marlowe et al. 1995; Martin 1998) are consistent with the standard picture of emission from the shocked outer shell of a classic wind-blown bubble (e.g. Weaver et al. 1977). Typical expansion velocities are 50 to 100 km s-1. Similarly, the morphology and kinematics of the emission-line gas in the outflows in edge-on starbursts like M 82, NGC 253, NGC 3079, and NGC 4945 imply that this material is flowing outward on the surface of a hollow bi-polar structure whose apices correspond to the starburst (e.g. Heckman, Armus, & Miley 1990; Shopbell & Bland-Hawthorn 1998; Cecil et al. 2001). The deprojected outflow speeds range from a few hundred to a thousand km s-1. This material is presumably ambient gas that has been entrained into the boundary layers of the bipolar hot wind, or perhaps the side walls of a ruptured superbubble (e.g. Suchkov et al. 1994; Strickland & Stevens 2000). In both superbubbles and superwinds, the optical emission-line gas is excited by some combination of wind-driven shocks and photoionization by the starburst.

Prior to the deployment of the Chandra X-ray observatory, it was

sometimes

assumed that the soft X-ray emission associated with superbubbles

and superwinds represented the primary wind fluid that filled

the volume bounded by the emission-line gas. If so, its relatively

low temperature (typically 0.5 to 1 kev) and high luminosity

(

![]() 10-4 to

10-3Lbol) required that substantial

mass-loading had occurred inside the starburst (

10-4 to

10-3Lbol) required that substantial

mass-loading had occurred inside the starburst (

![]()

![]() 10).

The situation is actually more complex.

The superb imaging capabilities of Chandra

demonstrate that the X-ray-emitting material bears a very

strong morphological relationship to the optical emission-line gas

(Strickland et al. 2000,

2001;

Martin, Kobulnicky, &

Heckman 2001).

The X-ray gas

also shows a limb-brightened filamentary structure,

and is either coincident with, or lies just to the "inside" of

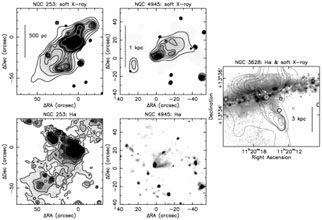

the emission-line filaments (Fig. 1). Thus, the

soft X-rays could arise in regions in which hydrodynamical processes at the

interface between the wind and interstellar medium have

mixed a substantial amount of dense ambient gas into the wind fluid,

greatly increasing the local X-ray emissivity. Alternatively, the

filaments may represent the side walls of a ruptured superbubble left behind

as the wind blows-out of a "thick-disk" component in the

interstellar medium. In this case the H

10).

The situation is actually more complex.

The superb imaging capabilities of Chandra

demonstrate that the X-ray-emitting material bears a very

strong morphological relationship to the optical emission-line gas

(Strickland et al. 2000,

2001;

Martin, Kobulnicky, &

Heckman 2001).

The X-ray gas

also shows a limb-brightened filamentary structure,

and is either coincident with, or lies just to the "inside" of

the emission-line filaments (Fig. 1). Thus, the

soft X-rays could arise in regions in which hydrodynamical processes at the

interface between the wind and interstellar medium have

mixed a substantial amount of dense ambient gas into the wind fluid,

greatly increasing the local X-ray emissivity. Alternatively, the

filaments may represent the side walls of a ruptured superbubble left behind

as the wind blows-out of a "thick-disk" component in the

interstellar medium. In this case the H![]() emission might trace

the forward shock driven into the halo gas and the X-rays the reverse

shock in the wind fluid (see

Lehnert, Heckman, &

Weaver 1999).

emission might trace

the forward shock driven into the halo gas and the X-rays the reverse

shock in the wind fluid (see

Lehnert, Heckman, &

Weaver 1999).

|

Figure 1. Soft X-ray and H |

Ambient interstellar material accelerated by the wind can also give

rise to blueshifted interstellar absorption-lines in starbursts. Our

(Heckman et al. 2000)

survey of the NaI![]() 5893

feature in a sample of several dozen starbursts showed that

the absorption-line profiles in the outflowing interstellar gas

spanned the range from near the galaxy

systemic velocity to a typical maximum blueshift of 400 to 600 km

s-1.

We argued this represented the terminal velocity reached by

interstellar clouds accelerated by the wind's ram pressure.

Very similar kinematics are observed in vacuum-UV absorption-lines in

local starbursts

(Heckman & Leitherer

1997;

Kunth et al. 1998;

Gonzalez-Delgado et

al. 1998).

This material

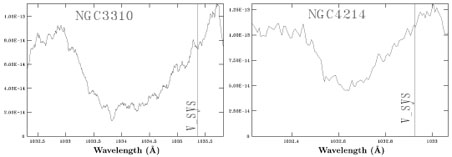

(Figure 2) ranges

from neutral gas probed by species like OI and CII to coronal-phase

gas probed by OVI

(Heckman et al. 2001a;

Martin et al. 2001).

Heckman et al. (2000)

showed that there are

substantial amounts of outflowing dust associated

with the neutral phase of the superwind. Radiation pressure may play

an important role in accelerating this material (e.g.

Aguirre 1999).

5893

feature in a sample of several dozen starbursts showed that

the absorption-line profiles in the outflowing interstellar gas

spanned the range from near the galaxy

systemic velocity to a typical maximum blueshift of 400 to 600 km

s-1.

We argued this represented the terminal velocity reached by

interstellar clouds accelerated by the wind's ram pressure.

Very similar kinematics are observed in vacuum-UV absorption-lines in

local starbursts

(Heckman & Leitherer

1997;

Kunth et al. 1998;

Gonzalez-Delgado et

al. 1998).

This material

(Figure 2) ranges

from neutral gas probed by species like OI and CII to coronal-phase

gas probed by OVI

(Heckman et al. 2001a;

Martin et al. 2001).

Heckman et al. (2000)

showed that there are

substantial amounts of outflowing dust associated

with the neutral phase of the superwind. Radiation pressure may play

an important role in accelerating this material (e.g.

Aguirre 1999).

|

Figure 2. FUSE spectra of the OVI |

Extended radio-synchrotron halos around starbursts imply that there is a magnetized relativistic component of the outflow. In the well-studied case of M 82, this relativistic plasma has evidently been advected out of the starburst by the primary energy-carrying wind fluid (Seaquist & Odegard 1991). The situation in NGC 253 is less clear (Beck et al. 1994; Strickland et al. 2001)