Possible constant, equilibrium values (or "fixed points") of X in equation (1) may be found algebraically by putting Xt+1 = Xt = X*, and solving the resulting equation

An equivalent graphical method is to find the points where the curve F(X) that maps Xt into Xt+1 intersects the 45° line, Xt+1 = Xt which corresponds to the ideal nirvana of zero population growth; see Fig. 1. For the single-hump curves discussed above, and exemplified by equations (3) and (4), there are two such points: the trivial solution X = 0, and a non-trivial solution X* (which for equation (3) is X* = 1 - (1/a).

The next question concerns the stability of the equilibrium point X*. This can be seen 24, 25, 19 - 21, 1, 4 to depend on the slope of the F(X) curve at X*. This slope, which is illustrated by the dashed lines in Fig. 1, can be designated

(X*) = [dF /

dX]x = x*

(6)

(X*) = [dF /

dX]x = x*

(6)

So long as this slope lies between 45° and -45° (that is,

(1)

between +1 and -1), making an acute angle with the 45° ZPG

line, the equilibrium point X* will be at least locally stable,

attracting all trajectories in its neighbourhood. In equation (3),

for example, this slope is

(1)

between +1 and -1), making an acute angle with the 45° ZPG

line, the equilibrium point X* will be at least locally stable,

attracting all trajectories in its neighbourhood. In equation (3),

for example, this slope is

(1) = 2 -

a: the equilibrium point is

therefore stable, and attracts all trajectories originating in the

interval 0 < X < 1, if and only if 1 < a < 3.

(1) = 2 -

a: the equilibrium point is

therefore stable, and attracts all trajectories originating in the

interval 0 < X < 1, if and only if 1 < a < 3.

As the relevant parameters are tuned so that the curve F(X)

becomes more and more steeply humped, this stability-determining

slope at X* may eventually steepen beyond -45° (that is,

(1) < -1),

whereupon the equilibrium point X* is no longer stable.

(1) < -1),

whereupon the equilibrium point X* is no longer stable.

What happens next? What happens, for example, for a > 3 in equation (3)?

To answer this question, it is helpful to look at the map which relates the populations at successive intervals 2 generations apart; that is, to look at the function which relates Xt+2 to Xt. This second iterate of equation (1) can be written

or, introducing an obvious piece of notation,

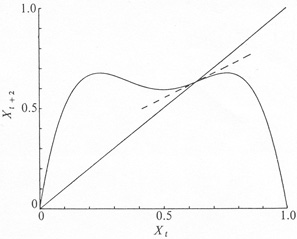

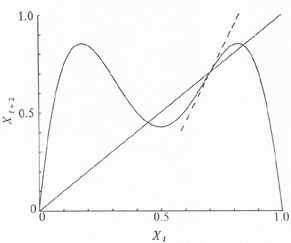

The map so derived from equation (3) is illustrated in Figs 2 and 3.

|

Figure 2. The map relating Xt+2 to Xt, obtained by two iterations of equation (3). This figure is for the case (a) of Fig. 1, a = 2.707: the basic fixed point is stable, and it is the only point at which F(2)(X) intersects the 45° line (where its slope, shown by the dashed line, is less steep than 45°). |

|

Figure 3. As for Fig. 2, except that here a = 3.414, as in Fig. 1b. The basic fixed point is now unstable: the slope of F(2)(X) at this point steepens beyond 45°, leading to the appearance of two new solutions of period 2. |

Population values which recur every second generation (that is, fixed points with period 2) may now be written as X*2, and found either algebraically from

or graphically from the intersection between the map

F(2)(X)

and the 45° line, as shown in Figs 2 and

3. Clearly the

equilibrium point X* of equation (5) is a solution of equation (9);

the basic fixed point of period 1 is a degenerate case of a period

2 solution. We now make a simple, but crucial, observation

1:

the slope of the curve F(2)(X) at the point

X*, defined as

(2)(X*)

and illustrated by the dashed lines in Figs 2

and 3, is

the square of the corresponding slope of F(X)

(2)(X*)

and illustrated by the dashed lines in Figs 2

and 3, is

the square of the corresponding slope of F(X)

(2) (X*)

= [

(2) (X*)

= [ (1)

(X*)]2

(10)

(1)

(X*)]2

(10)

This fact can now be used to make plain what happens when the

fixed point X* becomes unstable. If the slope of F(X) is

less than -45° (that is,

| (1)| < 1),

as illustrated by curve a in Fig. 1,

then X* is stable. Also, from equation (10), this implies 0 <

(1)| < 1),

as illustrated by curve a in Fig. 1,

then X* is stable. Also, from equation (10), this implies 0 <

(2) < 1

corresponding to the slope of F(2) at X* lying

between 0° and

45°, as shown in Fig. 2. As long as the

fixed point X* is stable, it

provides the only non-trivial solution to equation (9). On the

other hand, when

(2) < 1

corresponding to the slope of F(2) at X* lying

between 0° and

45°, as shown in Fig. 2. As long as the

fixed point X* is stable, it

provides the only non-trivial solution to equation (9). On the

other hand, when

(1) steepens

beyond -45° (that is,

|

(1) steepens

beyond -45° (that is,

| (1)| > 1),

as illustrated by curve b in

Fig 1, X* becomes

unstable. At the same time, from equation (10) this implies

(1)| > 1),

as illustrated by curve b in

Fig 1, X* becomes

unstable. At the same time, from equation (10) this implies

(2) > 1,

corresponding to the slope of F(2) at X*

steepening beyond 45°, as shown in

Fig. 3. As this happens, the curve

F(2)(X) must develop a "loop", and two new

fixed points of

period 2 appear, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

(2) > 1,

corresponding to the slope of F(2) at X*

steepening beyond 45°, as shown in

Fig. 3. As this happens, the curve

F(2)(X) must develop a "loop", and two new

fixed points of

period 2 appear, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

In short, as the nonlinear function F(X) in equation (1) becomes more steeply humped, the basic fixed point X* may become unstable. At exactly the stage when this occurs, there are born two new and initially stable fixed points of period 2, between which the system alternates in a stable cycle of period 2. The sort of graphical analysis indicated by Figs 1, 2 and 3, along with the equation (10), is all that is needed to establish this generic result 1, 4.

As before, the stability of this period 2 cycle depends on the

slope of the curve F(2)(X) at the 2

points. (This slope is easily shown to be the same at both points

1,

20,

and more generally to

be the same at all k points on a period k cycle.)

Furthermore, as

is clear by imagining the intermediate stages between

Figs 2 and

3, this stability-determining slope has the value

= +1 at the

birth of the 2-point cycle, and then decreases through zero

towards

= +1 at the

birth of the 2-point cycle, and then decreases through zero

towards  = -1 as the hump

in F(X) continues to steepen.

Beyond this point the period 2 points will in turn become

unstable, and bifurcate to give an initially stable cycle of period 4.

This in turn gives way to a cycle of period 8, and thence to a

hierarchy of bifurcating stable cycles of periods 16, 32, 64,...,

2n. In each case, the way in which a stable cycle of period

k

becomes unstable, simultaneously bifurcating to produce a new

and initially stable cycle of period 2k, is basically similar to the

process just adumbrated for k = 1. A more full and rigorous

account of the material covered so far is in ref. 1.

= -1 as the hump

in F(X) continues to steepen.

Beyond this point the period 2 points will in turn become

unstable, and bifurcate to give an initially stable cycle of period 4.

This in turn gives way to a cycle of period 8, and thence to a

hierarchy of bifurcating stable cycles of periods 16, 32, 64,...,

2n. In each case, the way in which a stable cycle of period

k

becomes unstable, simultaneously bifurcating to produce a new

and initially stable cycle of period 2k, is basically similar to the

process just adumbrated for k = 1. A more full and rigorous

account of the material covered so far is in ref. 1.

This "very beautiful bifurcation phenomenon" 22 is depicted in Fig. 4, for the example equation (3). It cannot be too strongly emphasised that the process is generic to most functions F(X) with a hump of tunable steepness. Metropolis et al. 16 refer to this hierarchy of cycles of periods 2n as the harmonics of the fixed point X*.

Although this process produces an infinite sequence of cycles

with periods 2n (n ->

), the "window" of parameter

values

wherein any one cycle is stable progressively diminishes, so that

the entire process is a convergent one, being bounded above by

some critical parameter value. (This is true for most, but not

all, functions F(X): see equation (17) below.) This critical

parameter value is a point of accumulation of period 2n cycles.

For equation (3) it is denoted ac :

ac = 3.5700...

), the "window" of parameter

values

wherein any one cycle is stable progressively diminishes, so that

the entire process is a convergent one, being bounded above by

some critical parameter value. (This is true for most, but not

all, functions F(X): see equation (17) below.) This critical

parameter value is a point of accumulation of period 2n cycles.

For equation (3) it is denoted ac :

ac = 3.5700...

Beyond this point of accumulation (for example, for a > ac in equation (3)) there are an infinite number of fixed points with different periodicities, and an infinite number of different periodic cycles. There are also an uncountable number of initial points X0 which give totally aperiodic (although bounded) trajectories; no matter how long the time series generated by F(X) is run out, the pattern never repeats. These facts may be established by a variety of methods 1, 4, 20, 22, 29. Such a situation, where an infinite number of different orbits can occur, has been christened "chaotic" by Li and Yorke20.

As the parameter increases beyond the critical value, at first all these cycles have even periods, with Xt alternating up and down between values above, and values below, the fixed point X*. Although these cycles may in fact be very complicated (having a non-degenerate period of, say, 5,726 points before repeating), they will seem to the casual observer to be rather like a somewhat "noisy" cycle of period 2. As the parameter value continues to increase, there comes a stage (at a = 3.6786.. for equation (3)) at which the first odd period cycle appears. At first these odd cycles have very long periods, but as the parameter value continues to increase cycles with smaller and smaller odd periods are picked up, until at last the three-point cycle appears (at a = 3.8284 . . for equation (3)). Beyond this point, there are cycles with every integer period, as well as an uncountable number of asymptotically aperiodic trajectories: Li and Yorke 20 entitle their original proof of this result "Period Three Implies Chaos".

The term "chaos" evokes an image of dynamical trajectories which are indistinguishable from some stochastic process. Numerical simulations 12, 15, 21, 23, 25 of the dynamics of equation (3), (4) and other similar equations tend to confirm this impression. But, for smooth and "sensible" functions F(X) such as in equations (3) and (4), the underlying mathematical fact is that for any specified parameter value there is one unique cycle that is stable, and that attracts essentially all initial points 22, 29 (see ref. 4, appendix A, for a simple and lucid exposition). That is, there is one cycle that "owns" almost all initial points; the remaining infinite number of other cycles, along with the asymptotically aperiodic trajectories, own a set of points which, although uncountable, have measure zero.

As is made clear by Tables 3 and 4 below, any one particular stable cycle is likely to occupy an extraordinarily narrow window of parameter values. This fact, coupled with the long time it is likely to take for transients associated with the initial conditions to damp out, means that in practice the unique cycle is unlikely to be unmasked, and that a stochastic description of the dynamics is likely to be appropriate, in spite of the underlying deterministic structure. This point is pursued further under the heading "practical applications", below.

The main messages of this section are summarised in Table 1, which sets out the various domains of dynamical behaviour of the equations (3) and (4) as functions of the parameters, a and r respectively, that determine the severity of the nonlinear response. These properties can be understood qualitatively in a graphical way, and are generic to any well behaved F(X) in equation (1).

| The function F(X) | aX; if X < ½ |  X; if

X < 1 X; if

X < 1

| ||

| of equation (1) | aX(1 - X) | X exp[r(1 - X)] | a(1 - X); if X > ½ |  X1-b;

if X > 1 X1-b;

if X > 1

|

| Tunable parameter | a | r | a | b |

| Fixed point becomes unstable | 3.0000 | 2.0000 | 1.0000* | 2.0000 |

| "Chaotic" region begins | ||||

| [point of accumulation of cycles of period 2n] | 3.5700 | 2.6924 | 1.0000 | 2.0000 |

| First odd-period cycle appears | 3.6786 | 2.8332 | 1.4142 | 2.6180 |

| Cycle with period 3 appears | ||||

| [and therefore every integer period present] | 3.8284 | 3.1024 | 1.6180 | 3.0000 |

| "Chaotic" region ends | 4.0000† |  ‡ ‡

| 2.000† |  ‡ ‡

|

| Are there stable cycles in the chaotic region? | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| * Below this a value, X = 0 is stable. | ||||

† All solutions are attracted to

- for a values

beyond this. for a values

beyond this.

| ||||

| ‡ In practice, as r or b becomes large enough, X will eventually be carried so low as to be effectively zero, thus producing extinction in models of biological populations. | ||||

We now proceed to a more detailed discussion of the mathematical structure of the chaotic regime for analytical functions, and then to the practical problems alluded to above and to a consideration of the behavioural peculiarities exhibited by non-analytical functions (such as those in the two right hand columns of Table 1).