| © CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS 2000 |

22.2. Spherical isotropic models

For systems such as globular clusters it is natural to look for a

description in terms of a distribution function dependent only on the

energy E = v2/2 +

(r). For these

small stellar systems, it is plausible that they have moved

significantly in the direction of a relaxed quasi-Maxwellian, with a

truncation

radius provided by the tidal environment where the globular cluster moves.

This is the basic physical motivation for solutions of the type

described in the

following section. It should be stressed that the main success of

these truncated models is that they can indeed provide a physically based

description of the global structure of an important class of stellar

systems. For comparison, we will later describe the classical isothermal

sphere

(which has infinite mass) and other tools (models obtained via adiabatic

deformations) that find their best applications to the local

structure of the cores of stellar systems.

(r). For these

small stellar systems, it is plausible that they have moved

significantly in the direction of a relaxed quasi-Maxwellian, with a

truncation

radius provided by the tidal environment where the globular cluster moves.

This is the basic physical motivation for solutions of the type

described in the

following section. It should be stressed that the main success of

these truncated models is that they can indeed provide a physically based

description of the global structure of an important class of stellar

systems. For comparison, we will later describe the classical isothermal

sphere

(which has infinite mass) and other tools (models obtained via adiabatic

deformations) that find their best applications to the local

structure of the cores of stellar systems.

22.2.1. Global truncated (King) models

Consider a spherical distribution of stars f = f

(E) limited to a sphere of

radius rt. The collection of stellar orbits described

by f is thus subject to the condition that f vanishes for

E >

(rt).

Suppose that the distribution function has the following form

(rt).

Suppose that the distribution function has the following form

|

(22.5) |

for E <

(rt)

(and f = 0 otherwise). Here A, a, and

rt

are free constants, defining two scales and one dimensionless

parameter. We may introduce the dimensionless "escape" energy

(rt)

(and f = 0 otherwise). Here A, a, and

rt

are free constants, defining two scales and one dimensionless

parameter. We may introduce the dimensionless "escape" energy

defined as

defined as

|

(22.6) |

Thus the condition E <

(rt)

can be written as av2/2 <

(rt)

can be written as av2/2 <

. The density profile (for

r < rt, i.e.

. The density profile (for

r < rt, i.e.

> 0) associated with the

distribution function is given by

> 0) associated with the

distribution function is given by

|

(22.7) |

By a simple change of integration variables the density can be written as

|

(22.8) |

with

|

(22.9) |

where  is

the incomplete Gamma function

(26). Note that the

density, in this isotropic model, depends on the radial coordinate

only implicitly through the potential

is

the incomplete Gamma function

(26). Note that the

density, in this isotropic model, depends on the radial coordinate

only implicitly through the potential

(r). For large

values of

(r). For large

values of  we have

we have

~

(3

~

(3 1/2/4)

exp(

1/2/4)

exp( ), i.e. it behaves like the

density of non-truncated isothermal models (see following section).

), i.e. it behaves like the

density of non-truncated isothermal models (see following section).

By a suitable rescaling of the radial coordinate

r

= r /

= r /

the self-consistency

relation implied by the Poisson equation can thus be written as

the self-consistency

relation implied by the Poisson equation can thus be written as

|

(22.10) |

which is to be integrated subject to the boundary conditions

(0) =

(0) =

> 0 and

> 0 and

'(0) = 0. Thus the

scalelength

'(0) = 0. Thus the

scalelength  can be

defined in terms of the central density

can be

defined in terms of the central density

0

and of the dimensionless depth of the central potential well

0

and of the dimensionless depth of the central potential well

by means of the relation

by means of the relation

|

(22.11) |

Close to the center the potential well can be approximated by a parabola with

|

(22.12) |

Integrating Eq. (10) out determines

the radius rt as the location where

vanishes. Thus a one-to-one

correspondence is found between

vanishes. Thus a one-to-one

correspondence is found between

and

rt /

and

rt /

. A commonly used

scalelength for this problem is

. A commonly used

scalelength for this problem is

|

(22.13) |

The one-parameter family of

models, usually called King models

(27) (see

Figs. 22.1 - 22.3),

is thus identified either by the value of

or, more

often, by the value of the concentration index

or, more

often, by the value of the concentration index

|

(22.14) |

As a model for elliptical galaxies

(28), the required

concentration parameter is in the range

2 < C < 2.35, although the R1/4 profile

is not reproduced in detail. Highly concentrated King models (formally

C

) go in the direction of

the isothermal sphere to be described below. It

should be stressed that, in spite of a being a constant, the velocity

dispersion associated with the distribution function of Eq. (5) is

not a

constant. The velocity dispersion monotonically decreases with radius

and vanishes at the truncation radius (see

Fig. 22.4).

) go in the direction of

the isothermal sphere to be described below. It

should be stressed that, in spite of a being a constant, the velocity

dispersion associated with the distribution function of Eq. (5) is

not a

constant. The velocity dispersion monotonically decreases with radius

and vanishes at the truncation radius (see

Fig. 22.4).

The radius r0 is sometimes confused with the "core

radius" rc of the

projected density distribution, usually defined as the location where the

projected density has dropped to one half of its central value. With the

definition of Eq. (13) the identification is correct for the

isothermal sphere (see below), and it is reasonable for concentrated King

models (29),

while at lower values of

the ratio

r0/rc changes

significantly with

the ratio

r0/rc changes

significantly with  .

.

Applications of these models to globular clusters have been very successful.

The globular clusters of our Galaxy

(30) are generally

well fitted by King models with concentration parameter in the range

0.5 < C < 2 (see Fig. 22.5);

some are even more concentrated, but they are generally considered to be in

a "post-core-collapse" phase, since the onset of the gravitational

catastrophe (31)

is known to take place at

7.4.

One can take full advantage of the equilibrium sequence by arguing

that the identifying parameters (total mass, central velocity

dispersion, and

concentration) can change as a result of evolutionary processes (such as

evaporation and disk-shocking), while the underlying model retains its King

appearance (32). By this

representation it is possible to follow the evolution of a whole

population of globular clusters in

a galaxy with a rather handy algorithm

(33), thus clarifying many

of the interesting correlations in the relevant parameter space observed

for the clusters of our Galaxy.

7.4.

One can take full advantage of the equilibrium sequence by arguing

that the identifying parameters (total mass, central velocity

dispersion, and

concentration) can change as a result of evolutionary processes (such as

evaporation and disk-shocking), while the underlying model retains its King

appearance (32). By this

representation it is possible to follow the evolution of a whole

population of globular clusters in

a galaxy with a rather handy algorithm

(33), thus clarifying many

of the interesting correlations in the relevant parameter space observed

for the clusters of our Galaxy.

We now consider the spherical analogue of the isothermal slab solution described in section 14.1 (in the context of the vertical equilibrium of a disk). That calculation was especially instructive, as a very simple case of a stellar dynamical study with distribution function priority. We may recall that the isothermal slab implied a constant gravity field at large distances from the plane [see Eq. (14.9)], so that, as a model of a galaxy disk, its interest was mostly for a self-consistent description of the vicinity of the equatorial plane.

Similarly, besides its general interest as indicative of the divergences intrinsic to the hypothesis of a fully relaxed stellar system, the spherical solution to be described below provides a useful representation of the local behavior of many stellar systems in their central regions. It can clarify some of the properties of the more physical King models (which have been successfully applied to the interpretation of the global luminosity profiles of globular clusters). In addition, it also turns out to describe much of the structure inside the half mass radius of the partially relaxed, finite mass models that will be found to incorporate the R1/4 profile (to be described in section 22.3).

If we take the distribution function

|

(22.15) |

with no restrictions on the star velocities, we get an isothermal equation of state given by

|

(22.16) |

with

|

(22.17) |

Here we have introduced the dimensionless potential

= -a

= -a

(r). Note that

the two constants A and a are

dimensional parameters that may be used in order to match some physical

scales of the system under investigation (e.g., the radius and the central

velocity dispersion in the core of a galaxy). In contrast with the King

models, there are no free dimensionless parameters available here. These

relations are in analogy to those of section 14.1.1 and should be

compared with

the corresponding equations of the previous section. The fully

self-consistent problem requires the solution of the Poisson equation

(r). Note that

the two constants A and a are

dimensional parameters that may be used in order to match some physical

scales of the system under investigation (e.g., the radius and the central

velocity dispersion in the core of a galaxy). In contrast with the King

models, there are no free dimensionless parameters available here. These

relations are in analogy to those of section 14.1.1 and should be

compared with

the corresponding equations of the previous section. The fully

self-consistent problem requires the solution of the Poisson equation

|

(22.18) |

The scalelength  is

defined via the relation [see Eq. (11)]

is

defined via the relation [see Eq. (11)]

|

(22.19) |

If we look for a solution with finite central density the natural

boundary conditions are  (0) =

(0) =

and

and

'(0) = 0. Since

no free dimensionless parameters are available, here we can choose the value

of

'(0) = 0. Since

no free dimensionless parameters are available, here we can choose the value

of  in such a way that

in such a way that

=

r0 (see Eq. (13). As is well

known in studies of polytropic stars, the isothermal solution beyond the

scale r0 becomes asymptotically close to

=

r0 (see Eq. (13). As is well

known in studies of polytropic stars, the isothermal solution beyond the

scale r0 becomes asymptotically close to

~

r-2, thus leading to

an integrated mass increasing linearly with radius and making it

inapplicable to describe the global profiles of stellar systems.

~

r-2, thus leading to

an integrated mass increasing linearly with radius and making it

inapplicable to describe the global profiles of stellar systems.

In the central regions [basically at radii r = O(r0)], the density profile that is obtained numerically, when projected along the line-of-sight is found to match the general behavior of galaxy cores. The projected density (here R denotes the projected radius) is very close to the so-called modified Hubble profile

|

(22.20) |

which can be traced to a volume density profile (34) of the form

|

(22.21) |

Obviously, the latter expressions find frequent applications because of their analytical simplicity.

One special solution with a singularity at the center is obtained when the

condition of finite central density is dropped. This singular

isothermal sphere corresponds to

= -2

ln(

= -2

ln( /

21/2), which

solves Eq. (18) exactly. Here the model loses the chacterization in

terms of the central density and becomes "self-similar". The

constants A and a are related to the constants b

and V0 of the

logarithmic spherical mass model of section 21.1.3 via the relations

a = 2/V02 and b = 21/2

/

21/2), which

solves Eq. (18) exactly. Here the model loses the chacterization in

terms of the central density and becomes "self-similar". The

constants A and a are related to the constants b

and V0 of the

logarithmic spherical mass model of section 21.1.3 via the relations

a = 2/V02 and b = 21/2

, with

, with

given by

Eq. (19).

The singular isothermal sphere presents close analogies with the isothermal

self-similar disk described in section 14.3.2, in relation to the

logarithmic

potential that is found and to the type of divergences occurring at

small and large radii. For the associated orbit structure we may thus

refer to section 21.1.3.

given by

Eq. (19).

The singular isothermal sphere presents close analogies with the isothermal

self-similar disk described in section 14.3.2, in relation to the

logarithmic

potential that is found and to the type of divergences occurring at

small and large radii. For the associated orbit structure we may thus

refer to section 21.1.3.

Historically, the study of the isothermal sphere finds its roots in the

theory of stellar structure, in relation to the Lane-Emden equation for

polytropic star models

(35). We recall that the

isotropic distribution function

f = A(- E)s for E < 0 (and

f = 0 otherwise), with

= 0 defining the

surface of the associated stellar system, generates a density distribution

= 0 defining the

surface of the associated stellar system, generates a density distribution

(r) =

B[-

(r) =

B[-  (r)]s+3/2. Here A, B are

constants. The Poisson equation thus becomes the same as the equation for a

polytropic sphere

(36) with index

n = s + 3/2. For the latter equation analytical

solutions are known for

n = 0, 1, 5. The case with n = 5 (with infinite radius)

is often considered for its simple analytical structure

(37). In particular the

associated Plummer density-potential pair is given by

(r)]s+3/2. Here A, B are

constants. The Poisson equation thus becomes the same as the equation for a

polytropic sphere

(36) with index

n = s + 3/2. For the latter equation analytical

solutions are known for

n = 0, 1, 5. The case with n = 5 (with infinite radius)

is often considered for its simple analytical structure

(37). In particular the

associated Plummer density-potential pair is given by

|

(22.22) |

|

(22.23) |

The integrated mass is given by

|

(22.24) |

so that the half-mass radius occurs at

rM  1.3b. The mean-square velocity is exactly

<v2> =

-

1.3b. The mean-square velocity is exactly

<v2> =

- (r) / 2 and the

projected density is given by

(r) / 2 and the

projected density is given by

|

(22.25) |

22.2.3. Galaxy cores and anisotropic models obtained via adiabatic growth

We have noted at the beginning of the previous subsection that different

emphasis can be given to the global or to a local

application of stellar dynamical models. On the small scale (r

<< rM) many models, such as King

models or the ones that will be introduced in

section 22.3, are characterized by a

quasi-isothermal core, in the sense that they behave approximately as the

(regular) isothermal sphere of

section 22.2.2. On the other hand nuclei of

galaxies have long been suspected to host massive point-like density

concentrations (possibly black holes). It is thus of great interest to

see whether

adequate self-consistent models can be constructed where the field is

due to the

sum of the contributions of the stellar system and of a central point-mass.

Clearly a comparison of the properties of these models with high resolution

photometric and spectroscopic observations should eventually tell which

galaxies host a central massive "black hole" and which do not. Major

projects have

been undertaken in the last few years focusing on these

issues (38).

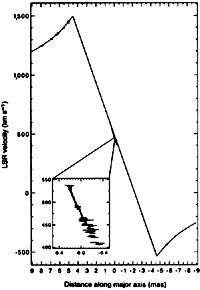

Either by means of stellar dynamical studies alone (in particular, for disk

galaxies, such as M 31, NGC 3115, NGC 4594, our Galaxy, and for

ellipticals (39), such

as M 32 and

NGC 3377) or with the help of kinematical data from

gas orbiting close to the

central nucleus (see the spectacular cases of the giant elliptical

M 87

and of the spiral galaxy NGC 4258 = M 106; see

Fig. 22.6) convincing evidence has been

accumulating for central black holes with masses in the range

2 × 106 - 3 × 109

M .

.

|

Figure 22.6. A radio observation suggesting the presence of a massive black hole at the center of the galaxy M 106 (Fig. 3 from Miyoshi, M., Moran, J., Herrnstein, J., Greenhill, L., et al. 1995, Nature (London), 373, 127). The plot gives the line-of-sight velocity as a function of radial distance (in milliarcseconds) from the center, along the major axis of the observed molecular disk, with data superimposed on a model curve described in the cited paper. At the distance of the object (estimated to be 6.4 Mpc), 8 mas define a length of 0.25 pc. |

Kinematical data are probably crucial to decide whether a central point-mass exists. Still it has been noted that, in the innermost regions (where the R1/4-like profile is usually smeared out by seeing from the ground (40)), in some cases the luminosity profile, when studied at sufficiently high spatial resolution, does flatten out into a core structure, while in others the profile increases basically as a power-law (41), as far in as it is possible to observe. With the aid of the Hubble Space Telescope, for a sample of dozens of ellipticals (and bulges) this behavior has been traced down to a scale of 1pc from the center. Curiously, some of the parameters that characterize the galactic nuclear regions are found to correlate strongly with more global parameters.

In this short subsection we will not go further into this fascinating

subject, but we will restrict our attention to some modeling issues that are

found to be interesting because of their simple physical motivation. In

contrast to the case without a central point mass, for which a core

structure is naturally

expected, in the presence of a 1/r singularity in the potential the

stellar system should display a central cusp in its density

distribution. In a study of this type, one important parameter is

clearly the ratio

M /

Mc of

the mass of the "black hole" to the mass of the core of the large-scale

stellar density distribution.

/

Mc of

the mass of the "black hole" to the mass of the core of the large-scale

stellar density distribution.

Originally, much of the attention was drawn to the case of

a black hole inside a collisional environment, such as that at the

center of a

globular cluster. Steady-state solutions of the Fokker-Planck equation were

sought and constructed, thus applicable to timescales longer than the

relevant two-body relaxation time

(42).

In the regime of small masses of the central black hole, under the

assumption that binary stars are unimportant, the cusp that is found is

approximately given by

~

r-7/4. In the following years, motivated by some of

the observational

studies mentioned above, the attention changed to the case of the more

collisionless galaxy cores. A recent revival of interest in collisional

steady-state solutions

(43) is

motivated by the fact that one may imagine even the center of a galaxy

to produce a collisional cusp via merging of small star clumps.

~

r-7/4. In the following years, motivated by some of

the observational

studies mentioned above, the attention changed to the case of the more

collisionless galaxy cores. A recent revival of interest in collisional

steady-state solutions

(43) is

motivated by the fact that one may imagine even the center of a galaxy

to produce a collisional cusp via merging of small star clumps.

The collisionless case suggests the likely presence of significant anisotropies very close to the central point mass. There radial orbits would feel selectively the influence of the central singularity. A first simple study can be performed by focusing on the region outside such a black hole dominated environment and can be obtained in terms of the so-called "loaded polytropes" (44). The basic idea is to see in such an outer region how the Lane-Emden equation is modified, thus reducing the discussion to that of a modified (isotropic) hydrostatic equilibrium with an assumed equation of state. One interesting finding of this much simplified description has been to show that a cusp structure forms, with properties that depend little on the polytropic index.

A more elegant construction of self-consistent stellar dynamical models can be made under the assumption that the central black hole grows slowly (on a time much longer than the relevant dynamical timescale) inside a pre-existing collisionless stellar system (thus on a time shorter than the relaxation time). In a spherical adiabatic growth (45) the orbits associated with the distribution function are modified but conserve their angular momentum and their radial action. The process thus shows in a very intuitive way how anisotropy can be generated out of an initially isotropic system by the growth of the central mass.

Without entering in all the details, we would like to record here the structure of the equations that describe spherical adiabatic evolution. Suppose we separate the potential in two parts, so that the energy integral is given by

|

(22.26) |

Here

ext0

is an external potential, while

ext0

is an external potential, while

0 is the

self-consistent potential generated by the density associated with the

distribution function f0(E, J)

describing the stellar system. We

recall that the radial action Jr is defined as

0 is the

self-consistent potential generated by the density associated with the

distribution function f0(E, J)

describing the stellar system. We

recall that the radial action Jr is defined as

|

(22.27) |

the function vr and the integral between the two turning points depend on the sum of the external and of the self-consistent potentials.

Now we can imagine that the external potential

be varied slowly, by changing one parameter

from its initial value

from its initial value

0, so that

it becomes

0, so that

it becomes

ext(r).

This change will induce a change in the self-consistent potential from

ext(r).

This change will induce a change in the self-consistent potential from

0(r)

to

0(r)

to  (r). In this

slow

process the radial action and the angular momentum are conserved, while the

energy is not. So we may imagine to start from an orbit characterized by

(E(0), J) in the potential

(r). In this

slow

process the radial action and the angular momentum are conserved, while the

energy is not. So we may imagine to start from an orbit characterized by

(E(0), J) in the potential

0(r) +

0(r) +

ext0(r) and arrive at an

orbit characterized by (E, J) in the potential

ext0(r) and arrive at an

orbit characterized by (E, J) in the potential

(r) +

(r) +

ext(r)

with the condition:

ext(r)

with the condition:

|

(22.28) |

This relation should be interpreted as a mapping between the "initial" value of the energy E(0) and the "final" value of the energy E required for the radial action to remain constant. In other words this gives implicitly a relation E(0) = E(0)(E, J). If we start from a distribution of stellar orbits f0, the final distribution function will thus be given by

|

(22.29) |

with E(0) determined from Eq. (28). Self-consistency requires

|

(22.30) |

These non-linear equations can be solved numerically (e.g., by iteration

procedures) to derive the effects of adiabatic evolution. In particular

one may consider the situation where

ext0

= 0 and f0 = f0(E) describes a

non-singular isothermal sphere [see Eq. (15)], and ask what will

be the final distribution function f (E, J) for

ext0

= 0 and f0 = f0(E) describes a

non-singular isothermal sphere [see Eq. (15)], and ask what will

be the final distribution function f (E, J) for

ext = - G

M

ext = - G

M /

r. The influence radius of the black hole is thus given by

r

/

r. The influence radius of the black hole is thus given by

r =

aG

M

=

aG

M ,

while the mass of the core can be defined from

r0 = aGMc. The density cusp is found

to be characterized by

,

while the mass of the core can be defined from

r0 = aGMc. The density cusp is found

to be characterized by

~

r-3/2 and associated with a kinematical cusp

<v2> ~ G

M

~

r-3/2 and associated with a kinematical cusp

<v2> ~ G

M /

r. For a small black hole the density cusp emerges

from the core

region, while for large black holes the transition to the outer

~ r-2 isothermal behavior occurs via an intermediate

~ r-5/2 profile, with

no distinct core left (see Fig. 22.7). The

cusp is quasi-isotropic, with a small tangential bias at intermediate

radii. These conclusions are changed if one starts

from initial functions significantly different from that of the non-singular

isothermal sphere. The extension to the case where some rotation and

flattening are present is not trivial.

/

r. For a small black hole the density cusp emerges

from the core

region, while for large black holes the transition to the outer

~ r-2 isothermal behavior occurs via an intermediate

~ r-5/2 profile, with

no distinct core left (see Fig. 22.7). The

cusp is quasi-isotropic, with a small tangential bias at intermediate

radii. These conclusions are changed if one starts

from initial functions significantly different from that of the non-singular

isothermal sphere. The extension to the case where some rotation and

flattening are present is not trivial.

Part of the structure of the solutions obtained by adiabatic growth can be

clarified analytically. For this purpose one may refer to regions of phase

space where the actions in the key mapping relation (28) can be

approximated analytically (see Chapter 21 for the Keplerian, the

logarithmic, and

the harmonic potentials). Another limit where one can proceed

semi-analytically is the linear regime, where the departures

f1 = f - f0 and

1 =

1 =

-

-

0 from the

initial configuration are small because

the change in the external potential

0 from the

initial configuration are small because

the change in the external potential

ext is small. The

linearized equations for adiabatic changes are

(46)

ext is small. The

linearized equations for adiabatic changes are

(46)

|

(22.31) |

|

(22.32) |

where E is given by Eq. (26) and the angle brackets denote a bounce orbit average over the unperturbed orbits

|

(22.33) |

Here  r is the

bounce time between the radial turning points

[see Eq. (13.15)]. These equations are a somewhat subtle zero-frequency

limit of the linear stability equations (see Chapter 23); they are also

well known within the plasma community

(47).

r is the

bounce time between the radial turning points

[see Eq. (13.15)]. These equations are a somewhat subtle zero-frequency

limit of the linear stability equations (see Chapter 23); they are also

well known within the plasma community

(47).

It is not clear how these tools can give a realistic representation of galactic nuclei (see also section 25.1.3 in Part five). They have been shown here mostly because they define an interesting and physically guided device to construct self-consistent equilibrium distribution functions with a central point mass and because they represent an instructive case. A scenario of this type and similar techniques may turn out to be useful to describe other situations of interest in stellar dynamics.

26 See Abramowitz, M., Stegun, I.A. (1970), op.cit., definition 6.5.2 Back.

27 King, I. R.

(1965), Astron. J., 70, 376;

(1966), Astron. J., 71, 64;

Michie, R.W.

(1963), Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 125, 127

and Michie, R.W., Bodenheimer, P.H.

(1963), Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 126, 269

considered the more general anisotropic distribution function, where

E  E + cJ2

Back.

E + cJ2

Back.

28 Kormendy, J. (1978), Astrophys. J., 218, 333; King, I.R. (1978), Astrophys. J., 222, 1 Back.

29 Peterson, C.J., King, I.R. (1975), Astron. J., 80, 427 Back.

30 Djorgovski, S.G., Meylan, G. (1994), Astron. J., 108, 1292 Back.

31 Antonov, V.A. (1962), Vest. Lenigrad Univ., 7, 135, translated in Proceedings IAU Symp. 113, ed. J. Goodman, P. Hut, Reidel, Dordrecht, p. 525; Lynden-Bell, D., Wood, R. (1968), Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 138, 495 Back.

32 King, I.R. (1966), Astron. J., 71, 64; Prata, S.W. (1971), Astron. J., 76, 1017 and 1029; Chernoff, D.F., Kochanek, C.S., Shapiro, S.L. (1986), Astrophys. J., 309, 183; Chernoff, D.F., Shapiro, S.L. (1987), Astrophys. J., 322, 113 Back.

33 Vesperini, E. (1997), Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 287, 915 Back.

34 See Rood, H.J., Page, T.L., Kintner, E.C., King, I.R. (1972), Astrophys. J., 175, 627 Back.

35 Eddington, A.S. (1926), Internal constitution of stars, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; Chandrasekhar, S. (1939), An introduction to the theory of stellar structure, University of Chicago, Chicago (reprinted by Dover, New York); Saslaw, W.C. (1985), Gravitational physics of stellar and galactic systems, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; see also Betti, E. (1880), Nuovo Cimento, 7, 26 Back.

36 see also Vandervoort, P.O. (1980), Astrophys. J., 240, 478 Back.

37 Plummer, H.C. (1915), Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 76, 107 Back.

38 See, for example, Kormendy, J., Richstone, D. (1995), Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys., 33, 581; Crane, P., Stiavelli, M., King, I.R., Deharveng, J.M., et al. (1993), Astron. J., 106, 1371; Faber, S.M., Tremaine, S., Ajhar, E.A., Byun, Y-I. et al., (1997), Astron. J., 114, 1771, and the many papers cited therein. In particular, for M 32 see van der Marel, R.P., de Zeeuw, P.T., Rix, H-W., Quinlan, G.D. (1997), Nature, 385, 610; for M87 see Harms, R.J., Ford, H.C., Tsvetanov, Z.I., Hartig, G.F. et al. (1994), Astrophys. J. Letters, 435, L35; for M 106 see Miyoshi, M., Moran, J., Herrnstein, J., Greenhill, L., et al. (1995), Nature, 373, 127 Back.

39 Other objects not mentioned here are also likely to possess a massive central black hole; e.g., for NGC 1399 see Stiavelli, M., Møller, P., Zeilinger, W.W., (1993), Astron. Astrophys., 277, 421 Back.

40 The failure of the R1/4 profile in the innermost regions was already noted by Lauer, T. (1985), Astrophys. J., 292, 104 and by others Back.

41 The classical case is that of M 87; see Young, P.J., Westphal, J.A., Kristian, J., Wilson, C.P., Landauer, F.P. (1978), Astrophys. J., 221, 721 Back.

42 Peebles, P.J.E. (1972), Astrophys. J., 178, 371; Bahcall, J.N., Wolf, R.A. (1976), Astrophys. J., 209, 214 Back.

43 Evans, N.W., Collett, J.L.

(1997), Astrophys. J. Letters, 480, L103

show that a steady-state cusp with

~

r-4/3 is a

self-consistent solution of the collisional Boltzmann equation

Back.

~

r-4/3 is a

self-consistent solution of the collisional Boltzmann equation

Back.

44 Huntley, J.M., Saslaw, W.C. (1975), Astrophys. J., 199, 328 Back.

45 Peebles, P.J.E. (1972), Gen. Rel. Grav., 3, 63; Young, P.H. (1980), Astrophys. J., 242, 1232; Goodman, J., Binney, J.J. (1984), Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 207, 511; Lee, M.H., Goodman, J. (1989), Astrophys. J., 343, 594; Cipollina, M., Bertin, G. (1994), Astron. Astrophys., 288, 43; Quinlan, G.D., Hernquist, L., Sigurdsson, S. (1995), Astrophys. J., 440, 554. The effects of a slowly growing (and also of a fast growing) black hole inside an initially triaxial model have been studied recently using N-body simulations by Merritt, D., Quinlan, G.D. (1998), Astrophys. J., 498, 625 Back.

46 Cipollina, M. (1992), Tesi di laurea, Pisa University; Cipollina, M., Bertin, G. (1994), Astron. Astrophys., 288, 43 Back.

47 See Antonsen, T.M., Lee, Y.C. (1982), Phys. Fluids, 25, 132 Back.