A. Growth curves

To repeat myself redundantly, the first dirty problem relates to the

fact that the

magnitudes which come from profile fitting are purely relative

magnitudes: they tell you

how much brighter or fainter the program star is than the star(s) which

defined the model

profile for that frame, but they do not tell you the instrumental

magnitude of each star

in absolute terms. In order to find out how bright each program star

really is, you need

to know exactly how many detected photons are contained in the actual

profile(s) of some

star(s) in the frame. This number is then divided by the integration

time to get the star's

apparent flux in photons per second, which is converted into an

instrumental magnitude on

an absolute system by computing -2.5log(flux). The

relative magnitude differences derived

by the profile-fitting photometry then allow you to place all the

program stars in the frame

on the same external system. Finally, relying on the stability of the

detector, you can

transform these results to true magnitudes on somebody's standard system

by comparing

them to instrumental magnitudes obtained in the same way for standard

stars, just as you would have done with data from a photomultiplier.

The problem here is the fact that the shape and size of a stellar image

are affected

by seeing, telescope focus, and guiding errors - any or all of which may

change from

one exposure to the next. Even if you write a profile-fitting photometry

program which

describes a frame's PSF with some analytic function, it is not

necessarily safe to assume

that you can simply integrate that function from minus infinity to plus

infinity in x and

y (or from zero to infinity in r), and call the result the

total number of detected photons

within the profile. In profile-fitting photometry, you adjust your

analytic model to obtain

the best possible representation of the core of the profile, where most

of the photometric

and astrometric information resides. If you want to be at all practical,

you are not likely to

include more than six or eight image-shape parameters in your analytic

star model. Once

these parameters have been adjusted to match the bright part of the

profile, there is no

guarantee that they will match the low surface-brightness, low

signal-to-noise-ratio wings

of the star image. Thus, when you come along and multiply this model

profile by 2  r dr

and integrate from zero to infinity, it's easy to believe that you might

make an error of a

few percent in the total volume under the profile. An error of a few

percent, of course, is completely intolerable.

r dr

and integrate from zero to infinity, it's easy to believe that you might

make an error of a

few percent in the total volume under the profile. An error of a few

percent, of course, is completely intolerable.

The easiest way to derive a consistent measure of the total number of

photons contained

in a star image is simply to draw a boundary around it, count the number

of photons

contained within the boundary, and subtract off the number of photons

found in an identical

region which contains no star. Of course, this is just synthetic

aperture photometry with a

big aperture. The main problem with this method is that the

signal-to-noise ratio tends to

be quite poor. Consider measuring the brightness of a star through a

series of concentric

apertures of increasing size. As the aperture gets bigger, of course, it

contains more and

more of the star's light - the signal increases. Once the aperture gets

big enough that it

contains most of the star's light, the rate of increase in the signal

for a given increase in

aperture radius declines rapidly: as the fraction of the star's flux

contained in the aperture

asymptotically approaches unity, successively larger apertures can only

add tiny amounts

of additional starlight. On the other hand, the amount of random noise

contained in the

aperture (readout noise, Poisson photon noise in the sky, and

small-spatial-scale errors in the

flat-field correction, mostly) increases as the square root of the

number of pixels, which is to

say linearly with the aperture radius. Furthermore, there are also

systematic errors to worry

about: the systematic error due to an incorrect estimate of the local

sky brightness, and

the likelihood of including some unrelated astronomical object in the

aperture. These grow

linearly as the area of the aperture, that is, as the

square of the radius. So, you can see that

as you increase the aperture radius, the signal grows slowly even as the

noise grows rapidly.

The signal-to-noise ratio of the measurement has a maximum at some

comparatively small

radius - a radius which usually is not large enough to contain all the

seeing and guiding

variations. If you try to use a larger aperture in order to get a more

complete measurement

of the star's flux, so you can compare this CCD frame to others with

different seeing and

guiding histories, you will get a measurement which is also much poorer.

The solution to this problem is to do the same as - and the opposite of

- what we

did before: we map and/or model the average stellar profile in the

frame. The part about

doing the opposite is that this time we pay no particular attention to

the shape of the

stellar core; instead we trace with the greatest possible precision way

in which the starlight is distributed at large radii.

The standard technique for doing this is pretty straightforward. You

choose a number

of bright, isolated stars in your data frame (if necessary you isolate

them yourself, by

using the known point-spread function and the results of the

profile-fitting photometry to

subtract any neighbor stars from the frame), and perform aperture

photometry through a

series of concentric apertures of increasing radius. Then you form the

magnitude differences

(aperture 2 - aperture 1), (aperture 3 - aperture 2), and so on, and

determine the average

value for each of these differences from your particular sample of stars

in the frame. Then

the average correction from any arbitrary aperture k to aperture

n is

For each star, you can now choose that aperture k which maximizes that

star's own, private,

personal, signal-to-noise ratio, and correct that measurement to a very

large aperture n

with the least possible loss of precision. The resulting large-aperture

magnitude may now

be compared to the magnitude index that was given to that same star by

the profile-fitting

routine, and the mean of all those differences tells you how to correct

all the profile-fitting

results from that frame to an absolute instrumental system which can be

intercompared from one frame to another.

Now you will say to me, "This business of computing average differences

from one

aperture to the next, and then summing them up to get the correction to

the largest aperture

all looks very complicated. Why don't you just observe the actual values

of (aperture n

- aperture k) for a bunch of stars, and average them

together." The answer is that when

you do it my way, you can often use many more stars and get a more

precise final result.

In many CCD frames there may be only one or two stars where you can

actually measure

a worthwhile magnitude in aperture n. Most stars will be so faint that

the signal-to-noise

ratio in the largest aperture is very poor. For other stars, there may

be a neighbor star close

enough to contaminate the photometry in the larger apertures, or there

may be a bad pixel

or a cosmic-ray event, or the star may be too close to the edge of the

frame. However, many

of these stars will still be measurable in some subset of smaller

apertures. By determining

the mean (aperture 2 - aperture 1) difference from all stars that can be

reliably measured

in apertures 1 and 2, and determining from

those stars that can

be measured in aperture 3 as well as in 2 and 1, and ..., and

determining the net correction

from each aperture to the largest by summing these mean differences, you

get the most

accurate possible determination of the frame's "growth curve," as this

set of magnitude corrections is known in the trade.

Not all is joy in Mudville yet, however. Sometimes you will run into a

frame where

no star can be measured in the largest apertures. And even if you do

have one or two

stars for which you can get some kind of measurement in the largest

aperture, you often wonder how good a magnitude correction you can get

from such ratty data. Can anything

be done to make things better? Well, it seems to me that the next stage

of development

of the growth-curve technique is to consider the consecutive-aperture

magnitude differences

from all the frames taken during the course of a night or an observing

run, and try to come

up with a more general set of rules governing the distribution of light

in the outer parts

of star images. Under the working hypothesis that seeing, guiding, and

optical problems

will be most pronounced near the center of the stellar profile, you

would then argue that if

you could find a set of CCD frames whose growth curves were similar at

small radii, you

would expect that they should be even more similar at large radii. By

somehow averaging

the outer growth curves for a number of similar frames, you would come

up with still more

accurate and robust corrections to the magnitude system of the largest

aperture.

Just combining the data from frames whose growth curves seem identical

at small radii

may be the simplest thing that we can do, but we can also do something

more sophisticated,

which will allow us to use nonlinear least squares (Oh boy, oh boy!). I

have been working

on a package which fits a family of analytic model profiles to all the

observed consecutive-aperture

magnitude differences from an entire observing run, to derive the best possible

aperture corrections for every frame in one grand and glorious

solution. The particular

family of analytic model profiles was suggested by an empirical study of

stellar images

published by Ivan King in 1971. Dr. King found that a typical star image

appears to consist

of three parts: the innermost part of the profile - the core - is quite

well represented

by a Gaussian function of radius (I mentioned this before, remember?),

which apparently

is determined mostly by the seeing. The outermost part of the profile -

the aureole - is

strongly non-Gaussian. In fact it is much better represented by an

inverse power law, with

an exponent slightly greater than 2. The aureole is apparently produced

by scattering, both

within the atmosphere and from scratches and dust in the optical system

itself. Between

the core and the aureole is a transition region which is neither

Gaussian nor a power law,

and is described by an exponential as well as by anything. The actual

physical cause of

this transition region is not immediately obvious - perhaps it has to do

with telescope

aberrations, or maybe it is caused by seeing variations during the

exposure (remember that

the sum of many different Gaussians is not itself a Gaussian) - but

whatever it is, it looks more or less like an exponential.

Here is the basic formula I use to represent King's profile analytically

(it looks a lot worse than it really is):

where r is a radial distance measured (in pixels) from the center of the

concentric apertures,

which are in turn assumed to be concentric with the star image;

Ri is a seeing- (guiding-,

defocusing-) related radial scale parameter for the i-th data frame; and

G, M, and H

represent King's three profile regimes: the core, the aureole, and the

intermediate transition

region. They are Gaussian, Moffat, and exponential functions, respectively:

In the reduction of the data from a given night or observing run, my

program computes a

separate value of the seeing-radius parameter Ri for each CCD

frame, but the values of the

other fitting parameters A, B, C, and D are required to be

the same for all frames. Since

the parameter Ri affects only the Gaussian and exponential

components, which dominate

at small radii, this model permits each CCD frame to have its own seeing

disk in the core,

while forcing all frames to have the same power-law aureole at large

radii. Not only is this

constraint physically plausible, it also seems to be borne out pretty

well by the available

data (at least for a given telescope at a given time). There are a few

other things I'd like to

point out about this model. (1) The parameter A affects the asymptotic

power-law slope of

the aureole, so that the model can adapt itself to the available data at

large radii. If the King

profile is to be physically reasonable, we must have A > 1; otherwise,

the total amount of flux

contained within the profile, when integrated to infinity, will

diverge. (2) The parameter B

describes the fraction of the stellar flux which is contained in the

seeing-independent part of

the profile. (3) The parameter C allows the program to adjust the

relative importance of the

Gaussian and exponential contributions to the seeing-dependent part of

the profile, for the

best possible match of the model to the data at small-to-intermediate

radii. (4) Similarly, the

parameter D allows the program to adjust the scale lengths of the

Gaussian and exponential

components relative to one another (although their ratio is required to

be constant for the

entire data set), for a still better match of the model to the data at

intermediate radii.

This model is applied only in a differential sense. That is, given a set

of instrumental

magnitude measurements mi,j,k through a set of

apertures k =

1, ... , n with radii rk

(rk > rk-1) for stars j = 1,

... , Ni in

frame i, we work with the observed magnitude differences

These values of  are fitted by

a robust least-squares technique to equations of the form

are fitted by

a robust least-squares technique to equations of the form

As I implied before, this growth-curve methodology is, in a way,

profile-fitting

photometry stood on its head. Instead of producing an accurate model of

the bright core

of a star image for the best possible relative intensity scaling, we are

now trying to get an

accurate model of the faint wings of the profile for the best possible

absolute determination of

the stellar flux. For the growth-curve analysis the detailed structure

of the star image inside

the smallest aperture is immaterial, because the only way the profile

inside the innermost

aperture influences the result is through the integral

0r1 I(r) (2

0r1 I(r) (2

r) dr, which

is merely a

constant contributing to the numerator and denominator for all the

magnitude differences.

r) dr, which

is merely a

constant contributing to the numerator and denominator for all the

magnitude differences.

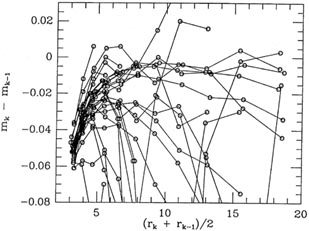

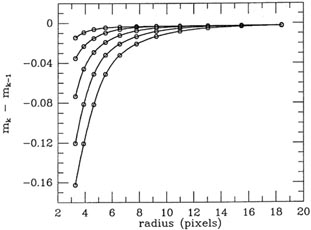

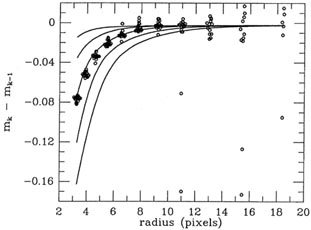

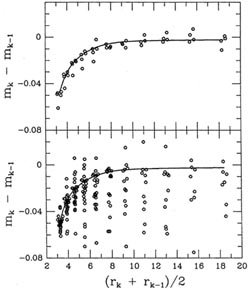

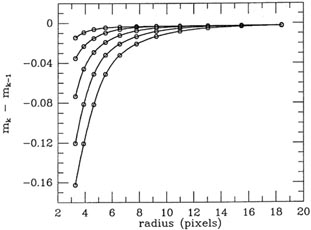

Figs. 5-1 to 5-4

show some examples of growth curves generated in this

way. Fig. 5-1

shows five members of the one-parameter family of growth curves which I

generated for an

observing run that I had in June 1988 at the prime focus of the Cerro

Tololo 4m telescope.

The uppermost curve is for the frame with the best seeing which I got

during the run, the

bottom curve is for the frame with the poorest seeing, and I have also

shown curves for three equally spaced intermediate seeing values.

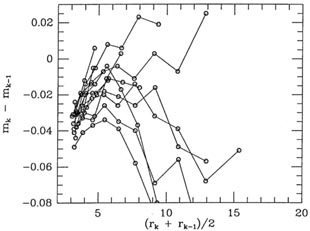

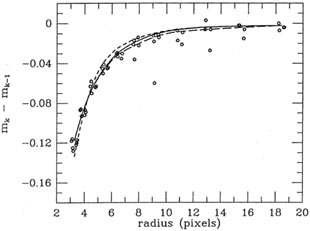

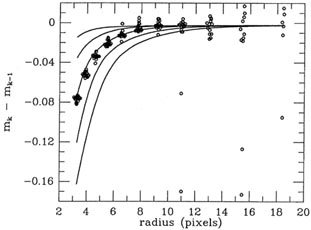

Fig. 5-2 shows how the raw magnitude

differences actually observed for the best-seeing frame compared to the

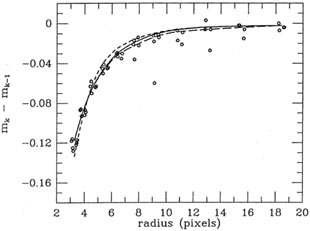

model, Fig. 5-3

shows the same for a frame of intermediate seeing, and finally

Fig. 5-4

shows the same for the frame with the poorest seeing.

|

| Figure 5-1.

|

|

| Figure 5-2.

|

|

| Figure 5-3.

|

|

| Figure 5-4.

|

Now let's consider some of the simplifying assumptions I have

made. First, in order to

improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the low-surface-brightness wings,

the two-dimensional

data have been compressed to a single, radial dimension by summation in

the azimuthal

direction - that's what the difference between two circular apertures

gives you. Second, I

have assumed that all the stellar profiles produced by a given

telescope/detector combination

can be represented by a single one-parameter family of curves differing

only in a seeing-imposed

radial scale-length parameter. Unfortunately, this assumption will not

be entirely

valid. There is no reason to assume that the effects of seeing are the

same as the effects

of guiding errors, telescope aberrations, defocusing, and aperture

decentering: each will

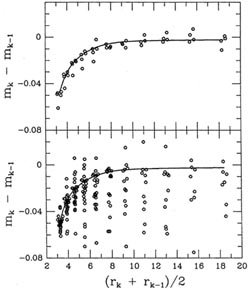

impose its own characteristic structures on the stellar

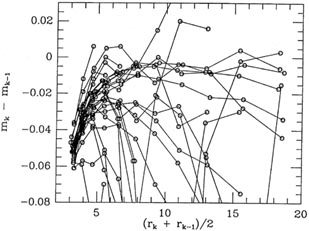

profile. Fig. 5-5 shows a frame from

the same observing run as the frames in

Fig. 5-2 to

Fig. 5-4; as you can see, it just plain

doesn't look like it belongs to quite the same family as the others. (I

must confess that this

is the most extreme example I have ever seen of a frame which departs

from its observing

run s one-parameter family of growth curves.) However, in spite of these

complications, I

think it may not be completely insane to hope that these profile

differences are reduced in

importance by the azimuthal summing, and furthermore I think we can hope

that they will

be most important in the smallest apertures; in the larger apertures, my

assumption of a

one-parameter family of growth curves may be asymptotically correct, at

least to within the precision of the observations.

|

| Figure 5-5.

|

My proposed solution to the problem is, in some ways, similar to the one

I adopted

in defining DAOPHOT's point-spread function: since the empirical growth

curve and the

analytic model growth curve both have problems, maybe we can do better

by combining

them. To be specific: in addition to deriving the best-fitting analytic

growth curve for each

frame, my routine also computes a standard, old-fashioned empirical

growth curve for each

frame, by taking robust averages of the aperture differences actually

observed in that frame.

Then it constructs the frame's adopted growth curve by compromising

between the empirical

growth curve and the analytic model growth curve. This compromise is

heavily weighted

toward the empirical curve at small aperture radii, since it is here

that the raw observations

are at their best: any given frame will contain many more stars which

can be effectively

measured through a small apertures than through large ones, and those

measurements

will contain the smallest random and systematic errors. Conversely, the

frame's adopted

growth curve is heavily biased toward the analytic curve at large

aperture radii, where the

frame may have only poorly determined raw magnitude differences or none

at all, but the

assumption that the run's growth curves can be described by a

one-parameter model should

be quite good. Fig. 5-6 shows the same data as

Fig. 5-5, only this time

the analytic model

growth curve (short dashes), the empirical growth curve (long dashes),

and the compromise

growth curve which is finally adopted for the frame (solid curve) are

all shown.

|

| Figure 5-6.

|

I don't need to tell you that in determining the empirical and the

analytic growth

curves, I use a form of the (a, b) weight-fudging scheme that I

described in my third lecture.

This time I use it with a slight twist. Unless you are extremely careful

in choosing the

particular stars you want to use to define your growth curves (and even

sometimes when

you are extremely careful), you're going to be including some just plain

awful magnitude

differences, because of small image defects or cosmic-ray events (it

doesn't take much to

screw up a measurement when you're hoping for precisions much better

than a percent).

Now the basic equation for the analytic model growth curve is rather

highly non-linear,

the various parameters interact pretty strongly with each other, and

starting guesses at

the parameter values are not necessarily obvious. If I use too strong a

clipping algorithm,

(small a, large b) I can get into trouble with non-unique

solutions. One likely scenario

is, depending on what I use as the starting guesses for the parameters,

the solution will

simply latch onto the observed growth curve for whatever star lies

closest, and ignore all the

others. On the other hand, if I use too weak a clipping function (large

a, perhaps combined

with small b), I may get garbage too, since some frames are just

so bad that not even the

median of the magnitude differences observed for a particular pair of

apertures may be close

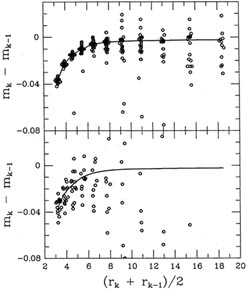

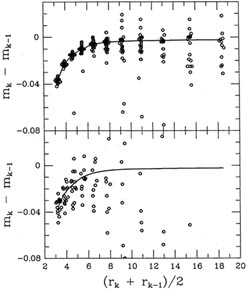

to the right answer (e.g., Figs. 5-7 and

5-8). Again I compromise. In the beginning, the

clipping function is used with a = 2 and

= 1. As I

discussed in the third lecture, this has

the effect of pulling the solution toward the median of the data points

(tinged toward the

mean of those data points with particularly small residuals). No datum

is so bad that it's

totally ignored. Even if the starting guesses are completely wrong,

still the solution will be

pulled into the center of the bulk of the data, rather than merely

latching onto whatever

lies closest to the starting guess. After the least-squares solution has

achieved a provisional

convergence with this clipping function, b is changed to 2

(a is left alone). This has the

effect of reducing the weights of the most discrepant points, while

slightly increasing the

weights of those points with small residuals (<

2

= 1. As I

discussed in the third lecture, this has

the effect of pulling the solution toward the median of the data points

(tinged toward the

mean of those data points with particularly small residuals). No datum

is so bad that it's

totally ignored. Even if the starting guesses are completely wrong,

still the solution will be

pulled into the center of the bulk of the data, rather than merely

latching onto whatever

lies closest to the starting guess. After the least-squares solution has

achieved a provisional

convergence with this clipping function, b is changed to 2

(a is left alone). This has the

effect of reducing the weights of the most discrepant points, while

slightly increasing the

weights of those points with small residuals (<

2 ); points with

moderate-to-large residuals

still carry some weight (a 4

); points with

moderate-to-large residuals

still carry some weight (a 4 residual still receives one-fifth weight, for instance. Look it

up: how often do you expect a

4

residual still receives one-fifth weight, for instance. Look it

up: how often do you expect a

4 residual with a Gaussian error

distribution? Do you still

believe that cookbook least squares is the only truly honest way to

reduce data?). This

allows the solution to shift itself a little closer to where the data

points are thickest - it

adjusts itself more toward the mode of the raw data. Finally,

after this least-squares

solution has achieved provisional convergence, b is changed to 3. This

suppresses the really

bad observations still further, and restores the weights of the data

with small residuals to

a value still closer to unity. With this mechanism, I get most of the

best of both worlds:

I'm not stuck with including the obviously bad data points in my

results, and yet I don't

get paradoxical or non-unique answers. Regardless of the starting

guesses the solution is

pulled reliably and repeatably into the midst of the concordant

observations. By this time

I have looked at literally thousands of such solutions, and in every

case the final solution

has looked pretty much like what I would have sketched through the data

by hand and

eye, given the same information as the computer had.

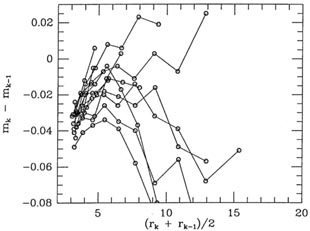

Figs. 5-9 and 5-10

show the growth curves that were fitted to the data shown in

Figs. 5-7 and 5-8; for

comparison, I also show

the growth curves for two frames of similar seeing which contain

good raw data.

residual with a Gaussian error

distribution? Do you still

believe that cookbook least squares is the only truly honest way to

reduce data?). This

allows the solution to shift itself a little closer to where the data

points are thickest - it

adjusts itself more toward the mode of the raw data. Finally,

after this least-squares

solution has achieved provisional convergence, b is changed to 3. This

suppresses the really

bad observations still further, and restores the weights of the data

with small residuals to

a value still closer to unity. With this mechanism, I get most of the

best of both worlds:

I'm not stuck with including the obviously bad data points in my

results, and yet I don't

get paradoxical or non-unique answers. Regardless of the starting

guesses the solution is

pulled reliably and repeatably into the midst of the concordant

observations. By this time

I have looked at literally thousands of such solutions, and in every

case the final solution

has looked pretty much like what I would have sketched through the data

by hand and

eye, given the same information as the computer had.

Figs. 5-9 and 5-10

show the growth curves that were fitted to the data shown in

Figs. 5-7 and 5-8; for

comparison, I also show

the growth curves for two frames of similar seeing which contain

good raw data.

|

| Figure 5-7.

|

|

| Figure 5-8.

|

It takes our VAX computer about half an hour to compute the adopted

growth curves

for a couple of hundred frames. How long do you think it would take me

with a pencil and

a stack of graph paper? Another triumph for (approximately) least

squares.

|

| Figure 5-9.

|

|

| Figure 5-10.

|

r dr

and integrate from zero to infinity, it's easy to believe that you might

make an error of a

few percent in the total volume under the profile. An error of a few

percent, of course, is completely intolerable.

r dr

and integrate from zero to infinity, it's easy to believe that you might

make an error of a

few percent in the total volume under the profile. An error of a few

percent, of course, is completely intolerable.

are fitted by

a robust least-squares technique to equations of the form

are fitted by

a robust least-squares technique to equations of the form

0r1 I(r) (2

0r1 I(r) (2

r) dr, which

is merely a

constant contributing to the numerator and denominator for all the

magnitude differences.

r) dr, which

is merely a

constant contributing to the numerator and denominator for all the

magnitude differences.

= 1. As I

discussed in the third lecture, this has

the effect of pulling the solution toward the median of the data points

(tinged toward the

mean of those data points with particularly small residuals). No datum

is so bad that it's

totally ignored. Even if the starting guesses are completely wrong,

still the solution will be

pulled into the center of the bulk of the data, rather than merely

latching onto whatever

lies closest to the starting guess. After the least-squares solution has

achieved a provisional

convergence with this clipping function, b is changed to 2

(a is left alone). This has the

effect of reducing the weights of the most discrepant points, while

slightly increasing the

weights of those points with small residuals (<

2

= 1. As I

discussed in the third lecture, this has

the effect of pulling the solution toward the median of the data points

(tinged toward the

mean of those data points with particularly small residuals). No datum

is so bad that it's

totally ignored. Even if the starting guesses are completely wrong,

still the solution will be

pulled into the center of the bulk of the data, rather than merely

latching onto whatever

lies closest to the starting guess. After the least-squares solution has

achieved a provisional

convergence with this clipping function, b is changed to 2

(a is left alone). This has the

effect of reducing the weights of the most discrepant points, while

slightly increasing the

weights of those points with small residuals (<

2 ); points with

moderate-to-large residuals

still carry some weight (a 4

); points with

moderate-to-large residuals

still carry some weight (a 4 residual still receives one-fifth weight, for instance. Look it

up: how often do you expect a

4

residual still receives one-fifth weight, for instance. Look it

up: how often do you expect a

4 residual with a Gaussian error

distribution? Do you still

believe that cookbook least squares is the only truly honest way to

reduce data?). This

allows the solution to shift itself a little closer to where the data

points are thickest - it

adjusts itself more toward the mode of the raw data. Finally,

after this least-squares

solution has achieved provisional convergence, b is changed to 3. This

suppresses the really

bad observations still further, and restores the weights of the data

with small residuals to

a value still closer to unity. With this mechanism, I get most of the

best of both worlds:

I'm not stuck with including the obviously bad data points in my

results, and yet I don't

get paradoxical or non-unique answers. Regardless of the starting

guesses the solution is

pulled reliably and repeatably into the midst of the concordant

observations. By this time

I have looked at literally thousands of such solutions, and in every

case the final solution

has looked pretty much like what I would have sketched through the data

by hand and

eye, given the same information as the computer had.

Figs. 5-9 and 5-10

show the growth curves that were fitted to the data shown in

Figs. 5-7 and 5-8; for

comparison, I also show

the growth curves for two frames of similar seeing which contain

good raw data.

residual with a Gaussian error

distribution? Do you still

believe that cookbook least squares is the only truly honest way to

reduce data?). This

allows the solution to shift itself a little closer to where the data

points are thickest - it

adjusts itself more toward the mode of the raw data. Finally,

after this least-squares

solution has achieved provisional convergence, b is changed to 3. This

suppresses the really

bad observations still further, and restores the weights of the data

with small residuals to

a value still closer to unity. With this mechanism, I get most of the

best of both worlds:

I'm not stuck with including the obviously bad data points in my

results, and yet I don't

get paradoxical or non-unique answers. Regardless of the starting

guesses the solution is

pulled reliably and repeatably into the midst of the concordant

observations. By this time

I have looked at literally thousands of such solutions, and in every

case the final solution

has looked pretty much like what I would have sketched through the data

by hand and

eye, given the same information as the computer had.

Figs. 5-9 and 5-10

show the growth curves that were fitted to the data shown in

Figs. 5-7 and 5-8; for

comparison, I also show

the growth curves for two frames of similar seeing which contain

good raw data.