The detection of cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies

(Bennett et al. 1996;

de Bernardis et al. 2000;

Hanany et al. 2000)

confirmed the notion that the present large-scale structure in the

universe originated from small-amplitude density fluctuations at early

times.

Due to the natural instability of gravity, regions that were denser than

average collapsed and formed bound objects, first on small spatial

scales and later on larger and larger scales. The present-day

abundance of bound objects, such as galaxies and X-ray clusters, can be

explained based on an appropriate extrapolation of the detected

anisotropies to smaller scales.

Existing observations with the Hubble Space Telescope (e.g.,

Steidel et al. 1996;

Madau et al. 1996;

Chen et al. 1999;

Clements et al. 1999)

and ground-based telescopes

(Lowenthal et al. 1997;

Dey et al. 1998;

Hu et al. 1998,

1999;

Spinrad et al. 1998;

Steidel et al. 1999),

have constrained the evolution of galaxies and their

stellar content at z

6. However, in the

bottom-up hierarchy of

the popular Cold Dark Matter (CDM) cosmologies, galaxies were

assembled out of building blocks of smaller mass. The elementary

building blocks, i.e., the first gaseous objects to form, acquired a

total mass of order the Jeans mass (~ 104

M

6. However, in the

bottom-up hierarchy of

the popular Cold Dark Matter (CDM) cosmologies, galaxies were

assembled out of building blocks of smaller mass. The elementary

building blocks, i.e., the first gaseous objects to form, acquired a

total mass of order the Jeans mass (~ 104

M ), below which

gas pressure opposed gravity and prevented collapse

(Couchman & Rees 1986;

Haiman & Loeb 1997;

Ostriker & Gnedin

1996).

In variants of

the standard CDM model, these basic building blocks first formed at

z ~ 15-30.

), below which

gas pressure opposed gravity and prevented collapse

(Couchman & Rees 1986;

Haiman & Loeb 1997;

Ostriker & Gnedin

1996).

In variants of

the standard CDM model, these basic building blocks first formed at

z ~ 15-30.

An important qualitative outcome of the microwave anisotropy data is the confirmation that the universe started out simple. It was by and large homogeneous and isotropic with small fluctuations that can be described by linear perturbation analysis. The current universe is clumpy and complicated. Hence, the arrow of time in cosmic history also describes the progression from simplicity to complexity (see Figure 1). While the conditions in the early universe can be summarized on a single sheet of paper, the mere description of the physical and biological structures found in the present-day universe cannot be captured by thousands of books in our libraries. The formation of the first bound objects marks the central milestone in the transition from simplicity to complexity. Pedagogically, it would seem only natural to attempt to understand this epoch before we try to explain the present-day universe. Historically, however, most of the astronomical literature focused on the local universe and has only been shifting recently to the early universe. This violation of the pedagogical rule was forced upon us by the limited state of our technology; observation of earlier cosmic times requires detection of distant sources, which is feasible only with large telescopes and highly-sensitive instrumentation.

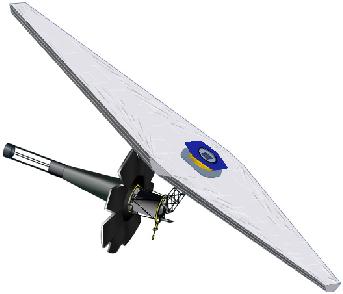

For these reasons, advances in technology are likely to make the high

redshift universe an important frontier of cosmology over the coming

decade. This effort will involve large (30 meter) ground-based

telescopes and will culminate in the launch of the successor to the

Hubble Space Telescope, called Next Generation Space

Telescope (NGST). Figure 2 shows an

artist's illustration

of this telescope which is currently planned for launch in 2009.

NGST will image the first sources of light that formed in the

universe. With its exceptional sub-nJy (1 nJy =

10-32erg cm-2

s-1 Hz-1) sensitivity in the 1-3.5

µm infrared

regime, NGST is ideally suited for probing optical-UV emission from

sources at redshifts  10, just when popular Cold Dark Matter

models for structure formation predict the first baryonic objects to

have collapsed.

10, just when popular Cold Dark Matter

models for structure formation predict the first baryonic objects to

have collapsed.

|

Figure 2. Artist's illustration of one of the current designs (GSFC) of the Next Generation Space Telescope. More details about the telescope can be found at http://ngst.gsfc.nasa.gov/. |

The study of the the formation of the first generation of sources at early cosmic times (high redshifts) holds the key to constraining the power-spectrum of density fluctuations on small scales. Previous research in cosmology has been dominated by studies of Large Scale Structure (LSS); future studies are likely to focus on Small Scale Structure (SSS).

The first sources are a direct consequence of the growth of linear density fluctuations. As such, they emerge from a well-defined set of initial conditions and the physics of their formation can be followed precisely by computer simulation. The cosmic initial conditions for the formation of the first generation of stars are much simpler than those responsible for star formation in the Galactic interstellar medium at present. The cosmic conditions are fully specified by the primordial power spectrum of Gaussian density fluctuations, the mean density of dark matter, the initial temperature and density of the cosmic gas, and the primordial composition according to Big-Bang nucleosynthesis. The chemistry is much simpler in the absence of metals and the gas dynamics is much simpler in the absence of both dynamically-significant magnetic fields and feedback from luminous objects.

The initial mass function of the first stars and black holes is therefore determined by a simple set of initial conditions (although subsequent generations of stars are affected by feedback from photoionization heating and metal enrichment). While the early evolution of the seed density fluctuations can be fully described analytically, the collapse and fragmentation of nonlinear structure must be simulated numerically. The first baryonic objects connect the simple initial state of the universe to its complex current state, and their study with hydrodynamic simulations (e.g., Abel et al. 1998a, Abel, Bryan, & Norman 2000; Bromm, Coppi, & Larson 1999) and with future telescopes such as NGST offers the key to advancing our knowledge on the formation physics of stars and massive black holes.

The first light from stars and quasars ended the ``dark

ages''

(2) of the universe and initiated a

``renaissance of

enlightenment'' in the otherwise fading glow of the microwave

background (see Figure 1). It is easy to see why

the mere

conversion of trace amounts of gas into stars or black holes at this

early epoch could have had a dramatic effect on the ionization state

and temperature of the rest of the gas in the universe. Nuclear fusion

releases ~ 7 × 106 eV per hydrogen atom, and thin-disk

accretion onto a Schwarzschild black hole releases ten times more

energy; however, the ionization of hydrogen requires only 13.6 eV. It

is therefore sufficient to convert a small fraction, ~ 10-5 of

the total baryonic mass into stars or black holes in order to ionize

the rest of the universe. (The actual required fraction is higher by

at least an order of magnitude

[Bromm, Kudritzky, &

Loeb 2000]

because only some of the emitted photons are above the ionization

threshold of 13.6 eV and because each hydrogen atom recombines more

than once at redshifts z

7). Recent

calculations of structure

formation in popular CDM cosmologies imply that the universe was

ionized at z ~ 7-12

(Haiman & Loeb 1998,

1999b,

c;

Gnedin & Ostriker

1997;

Chiu & Ostriker 2000;

Gnedin 2000a).

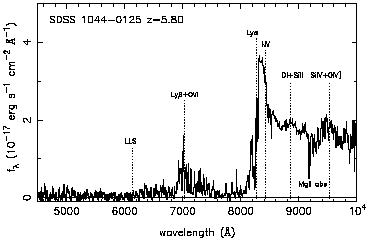

Current observations are at the threshold of probing this epoch of

reionization, given the fact that galaxies and quasars at redshifts

~ 6 are being discovered

(Fan et al. 2000;

Stern et al. 2000).

One of these sources is a bright quasar at z = 5.8 whose

spectrum is shown in Figure 3. The plot

indicates that there is transmitted flux short-ward of the

Ly

7). Recent

calculations of structure

formation in popular CDM cosmologies imply that the universe was

ionized at z ~ 7-12

(Haiman & Loeb 1998,

1999b,

c;

Gnedin & Ostriker

1997;

Chiu & Ostriker 2000;

Gnedin 2000a).

Current observations are at the threshold of probing this epoch of

reionization, given the fact that galaxies and quasars at redshifts

~ 6 are being discovered

(Fan et al. 2000;

Stern et al. 2000).

One of these sources is a bright quasar at z = 5.8 whose

spectrum is shown in Figure 3. The plot

indicates that there is transmitted flux short-ward of the

Ly wavelength at the

quasar redshift. The optical depth at these wavelengths of the

uniform cosmic gas in the intergalactic medium is however

(Gunn & Peterson

1965),

wavelength at the

quasar redshift. The optical depth at these wavelengths of the

uniform cosmic gas in the intergalactic medium is however

(Gunn & Peterson

1965),

| (1) |

where H  100h km s-1 Mpc-1

100h km s-1 Mpc-1

m1/2

(1 + zs)3/2 is the Hubble

parameter at the source redshift zs,

f

m1/2

(1 + zs)3/2 is the Hubble

parameter at the source redshift zs,

f = 0.4162 and

= 0.4162 and

= 1216Å are the

oscillator strength and the

wavelength of the Ly

= 1216Å are the

oscillator strength and the

wavelength of the Ly transition; nH I(zs) is the neutral

hydrogen density at the source redshift (assuming primordial

abundances);

transition; nH I(zs) is the neutral

hydrogen density at the source redshift (assuming primordial

abundances);  m

and

m

and  b are the

present-day density

parameters of all matter and of baryons, respectively; and

xH I

is the average fraction of neutral hydrogen. In the second equality we

have implicitly considered high redshifts (see

equations (9) and (10) in Section 2.1).

Modeling of the transmitted flux

(Fan et al. 2000)

implies

b are the

present-day density

parameters of all matter and of baryons, respectively; and

xH I

is the average fraction of neutral hydrogen. In the second equality we

have implicitly considered high redshifts (see

equations (9) and (10) in Section 2.1).

Modeling of the transmitted flux

(Fan et al. 2000)

implies  s < 0.5 or

xH I

s < 0.5 or

xH I  10-6, i.e., the low-density gas

throughout the universe is fully ionized at z = 5.8! One of the

important challenges for future observations will be to identify when

and how the intergalactic medium was ionized. Theoretical

calculations (see Section 6.3.1) imply

that such observations are just around the corner.

10-6, i.e., the low-density gas

throughout the universe is fully ionized at z = 5.8! One of the

important challenges for future observations will be to identify when

and how the intergalactic medium was ionized. Theoretical

calculations (see Section 6.3.1) imply

that such observations are just around the corner.

|

Figure 3. Optical spectrum of the highest-redshift known quasar at z = 5.8, discovered by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (Fan et al. 2000). |

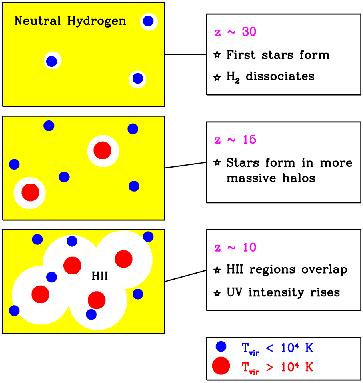

Figure 4 shows schematically the various stages in a

theoretical scenario for the history of hydrogen reionization in the

intergalactic medium. The first gaseous clouds collapse at redshifts

~ 20-30 and fragment into stars due to molecular hydrogen

(H2) cooling. However, H2 is fragile and can be easily

dissociated by a small flux of UV radiation. Hence the bulk of the

radiation that ionized the universe is emitted from galaxies with a

virial temperature  104 K, where atomic cooling is effective and

allows the gas to fragment (see the end of

Section 3.3 for an alternative scenario).

104 K, where atomic cooling is effective and

allows the gas to fragment (see the end of

Section 3.3 for an alternative scenario).

|

Figure 4. Stages in the reionization of hydrogen in the intergalactic medium. |

Since recent observations confine the standard set of cosmological

parameters to a relatively narrow range, we assume a

CDM

cosmology with a particular standard set of parameters in the

quantitative results in this review. For the contributions to the

energy density, we assume ratios relative to the critical density of

CDM

cosmology with a particular standard set of parameters in the

quantitative results in this review. For the contributions to the

energy density, we assume ratios relative to the critical density of

m = 0.3,

m = 0.3,

= 0.7, and

= 0.7, and

b = 0.045, for

matter, vacuum

(cosmological constant), and baryons, respectively. We also assume a

Hubble constant

H0 = 70 km s-1Mpc-1, and a

primordial scale invariant (n = 1) power spectrum with

b = 0.045, for

matter, vacuum

(cosmological constant), and baryons, respectively. We also assume a

Hubble constant

H0 = 70 km s-1Mpc-1, and a

primordial scale invariant (n = 1) power spectrum with

8 = 0.9,

where

8 = 0.9,

where  8 is the

root-mean-square amplitude of mass

fluctuations in spheres of radius 8 h-1 Mpc. These parameter

values are based primarily on the following observational results: CMB

temperature anisotropy measurements on large scales

(Bennett et al. 1996)

and on the scale of ~ 1°

(Lange et al. 2000;

Balbi et al. 2000);

the abundance of galaxy clusters locally

(Viana & Liddle 1999;

Pen 1998;

Eke, Cole, & Frenk

1996)

and as a function of redshift

(Bahcall & Fan 1998;

Eke, Cole, Frenk, &

Henry 1998);

the baryon density inferred from big bang nucleosynthesis (see the review

by Tytler et al. 2000);

distance measurements used to derive the

Hubble constant

(Mould et al. 2000;

Jha et al. 1999;

Tonry et al. 1997);

and indications of cosmic acceleration from distances based on

type Ia supernovae

(Perlmutter et al. 1999;

Riess et al. 1998).

8 is the

root-mean-square amplitude of mass

fluctuations in spheres of radius 8 h-1 Mpc. These parameter

values are based primarily on the following observational results: CMB

temperature anisotropy measurements on large scales

(Bennett et al. 1996)

and on the scale of ~ 1°

(Lange et al. 2000;

Balbi et al. 2000);

the abundance of galaxy clusters locally

(Viana & Liddle 1999;

Pen 1998;

Eke, Cole, & Frenk

1996)

and as a function of redshift

(Bahcall & Fan 1998;

Eke, Cole, Frenk, &

Henry 1998);

the baryon density inferred from big bang nucleosynthesis (see the review

by Tytler et al. 2000);

distance measurements used to derive the

Hubble constant

(Mould et al. 2000;

Jha et al. 1999;

Tonry et al. 1997);

and indications of cosmic acceleration from distances based on

type Ia supernovae

(Perlmutter et al. 1999;

Riess et al. 1998).

This review summarizes recent theoretical advances in understanding the physics of the first generation of cosmic structures. Although the literature on this subject extends all the way back to the sixties (Saslaw & Zipoy 1967, Peebles & Dicke 1968, Hirasawa 1969, Matsuda et al. 1969, Hutchins 1976, Silk 1983, Palla et al. 1983, Lepp & Shull 1984, Couchman 1985, Couchman & Rees 1986, Lahav 1986), this review focuses on the progress made over the past decade in the modern context of CDM cosmologies.

2 The use of this term in the cosmological context was coined by Sir Martin Rees. Back.