The spatial distribution of galaxies can be measured either in two

dimensions as projected onto the plane of the sky or in three

dimensions using the redshift of each galaxy. As it can be

observationally expensive to obtain spectra for large samples of

(particularly faint) galaxies, redshift information is not always

available for a given sample. One can then measure the

two-dimensional projected angular correlation function

(

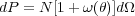

( ), defined as

the probability above Poisson of finding two galaxies with an angular

separation

), defined as

the probability above Poisson of finding two galaxies with an angular

separation  :

:

|

(5) |

where N is the mean number of galaxies per steradian and

d is the solid angle of a second galaxy at a separation

is the solid angle of a second galaxy at a separation

from a

randomly chosen galaxy.

from a

randomly chosen galaxy.

Measurements of

(

( ) are known to

be low by an additive factor known

as the "integral constraint", which results from using the data

sample itself (which often does not cover large areas of the sky) to

estimate the mean galaxy density. This correction becomes important

on angular scales comparable to the survey size; on much smaller

scales it is negligible. One can either restrict measurements of the

angular clustering to scales where the integral constraint is not

important or estimate the amplitude of the integral constraint

correction by doubly integrating an assumed power law form of

) are known to

be low by an additive factor known

as the "integral constraint", which results from using the data

sample itself (which often does not cover large areas of the sky) to

estimate the mean galaxy density. This correction becomes important

on angular scales comparable to the survey size; on much smaller

scales it is negligible. One can either restrict measurements of the

angular clustering to scales where the integral constraint is not

important or estimate the amplitude of the integral constraint

correction by doubly integrating an assumed power law form of

(

( ) over the

survey area,

) over the

survey area,  , using

, using

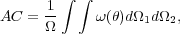

|

(6) |

where  is the area

subtended by the survey. In practice, this can be numerically estimated

over the survey geometry using the random catalog itself (see

Roche & Eales 1999 for details).

is the area

subtended by the survey. In practice, this can be numerically estimated

over the survey geometry using the random catalog itself (see

Roche & Eales 1999 for details).

The projected angular two-point correlation function,

(

( ),

can generally be fit with a power law,

),

can generally be fit with a power law,

|

(7) |

where A is the clustering amplitude at a given scale (often 1')

and  is the slope of the

correlation function.

is the slope of the

correlation function.

From measurements of

(

( ) one can infer the

three-dimensional spatial two-point correlation function,

) one can infer the

three-dimensional spatial two-point correlation function,

(r), if

the redshift distribution

of the sources is well known. The two-point correlation function,

(r), if

the redshift distribution

of the sources is well known. The two-point correlation function,

(r), is

usually fit as a power law,

(r), is

usually fit as a power law,

(r) =

(r / r0)-

(r) =

(r / r0)- ,

where r0 is the characteristic scale-length of the galaxy

clustering, defined as the scale at which

,

where r0 is the characteristic scale-length of the galaxy

clustering, defined as the scale at which

= 1. As the

two-dimensional galaxy clustering seen in the plane of the sky is a

projection of the three-dimensional clustering,

= 1. As the

two-dimensional galaxy clustering seen in the plane of the sky is a

projection of the three-dimensional clustering,

(

( ) is directly

related to its three-dimensional analog

) is directly

related to its three-dimensional analog

(r).

For a given

(r).

For a given

(r),

one can predict the amplitude and slope of

(r),

one can predict the amplitude and slope of

(

( ) using Limber's equation,

effectively integrating

) using Limber's equation,

effectively integrating

(r)

along the redshift direction (e.g.

Peebles 1980).

If one assumes

(r)

along the redshift direction (e.g.

Peebles 1980).

If one assumes

(r)

(and thus

(r)

(and thus

(

( )) to be a power

law over the redshift range of interest, such that

)) to be a power

law over the redshift range of interest, such that

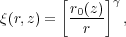

|

(8) |

then

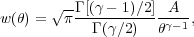

|

(9) |

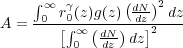

where Γ is the usual gamma function. The amplitude factor, A, is given by

|

(10) |

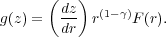

where dN / dz is the number of

galaxies per unit redshift interval and g(z) depends on

and the

cosmological model:

and the

cosmological model:

|

(11) |

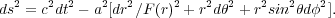

Here F(r) is the curvature factor in the Robertson-Walker metric,

|

(12) |

If the redshift distribution of sources,

dN / dz, is well known, then the amplitude of

(

( ) can be predicted for a

given power law model of

) can be predicted for a

given power law model of

(r),

such that measurements of

(r),

such that measurements of

(

( ) can

be used to place constraints on the evolution of

) can

be used to place constraints on the evolution of

(r).

(r).

Interpreting angular clustering results can be difficult, however, as

there is a degeneracy between the inherent clustering amplitude and

the redshift distribution of the sources in the sample. For example,

an observed weakly clustered signal projected on the plane of the sky

could be due either to the galaxy population being intrinsically

weakly clustered and projected over a relatively short distance along

the line of sight, or it could result from an inherently strongly

clustered distribution integrated over a long distance, which would

wash out the signal. The uncertainty on the redshift distribution is

therefore often the dominant error in analyses using angular

clustering measurements. The assumed galaxy redshift distribution

(dN / dz) has varied widely in different studies, such

that similar

observed angular clustering results have led to widely different

conclusions. A further complication is that each sample usually spans

a large range of redshifts and is magnitude-limited, such that the

mean intrinsic luminosity of the galaxies is changing with redshift

within a sample, which can hinder interpretation of the evolution of

clustering measured in  (

( ) studies.

) studies.

Many of the first measurements of large scale structure were studies

of angular clustering. One of the earliest determinations was the

pioneering work of

Peebles (1975)

using photographic plates from the

Lick survey (Fig. 1). They found

(

( ) to be well fit by a power

law with a slope of

) to be well fit by a power

law with a slope of  =

-0.8. Later studies using CCDs were able to

reach deeper magnitude limits and found that fainter galaxies had a

lower clustering amplitude. One such study was conducted by

Postman et

al. (1998),

who surveyed a contiguous 4° by 4° field

to a depth of IAB = 24 mag, reaching to z ~

1. Later surveys that covered multiple fields on the sky found similar

results. The lower clustering amplitude observed for galaxies with fainter

apparent magnitudes can in principle be due either to clustering

being a function of luminosity and/or a function of redshift. To

disentangle this dependence, each author assumes a dN/dz

distribution for galaxies as a function of apparent magnitude and then

fits the observed

=

-0.8. Later studies using CCDs were able to

reach deeper magnitude limits and found that fainter galaxies had a

lower clustering amplitude. One such study was conducted by

Postman et

al. (1998),

who surveyed a contiguous 4° by 4° field

to a depth of IAB = 24 mag, reaching to z ~

1. Later surveys that covered multiple fields on the sky found similar

results. The lower clustering amplitude observed for galaxies with fainter

apparent magnitudes can in principle be due either to clustering

being a function of luminosity and/or a function of redshift. To

disentangle this dependence, each author assumes a dN/dz

distribution for galaxies as a function of apparent magnitude and then

fits the observed

(

( ) with different models of

the redshift dependence of clustering. While many authors measure

similar values of the dependence of

) with different models of

the redshift dependence of clustering. While many authors measure

similar values of the dependence of

(

( ) on apparent magnitude, due

to differences

in the assumed dN / dz distributions different conclusions are

reached regarding the amount of luminosity and redshift dependence to

galaxy clustering. Additionally, quoted error bars on the inferred

values of r0 generally include only Poisson and/or

cosmic variance

error estimates, while the dominant error is often the lack of

knowledge of dN / dz for the particular sample in question.

) on apparent magnitude, due

to differences

in the assumed dN / dz distributions different conclusions are

reached regarding the amount of luminosity and redshift dependence to

galaxy clustering. Additionally, quoted error bars on the inferred

values of r0 generally include only Poisson and/or

cosmic variance

error estimates, while the dominant error is often the lack of

knowledge of dN / dz for the particular sample in question.

Because of the sensitivity of the inferred value of r0 on the redshift distribution of sources, it is preferable to measure the three dimensional correlation function. While it is much easier to interpret three dimensional clustering measurements, in cases where it is still not feasible to obtain redshifts for a large fraction of galaxies in the sample, angular clustering measurements are still employed. This is currently the case in particular with high redshift and/or very dusty, optically-obscured galaxy samples, such as sub-millimeter galaxies (e.g., Brodwin et al. 2008, Maddox et al. 2010). However, without knowledge of the redshift distribution of the sources, these measurements are hard to interpret.