We have seen that inflation is a powerful and predictive theory of the physics of the very early universe. Unexplained properties of a standard FRW cosmology, namely the flatness and homogeneity of the universe, are natural outcomes of an inflationary expansion. Furthermore, inflation provides a mechanism for generating the tiny primordial density fluctuations that seed the later formation of structure in the universe. Inflation makes definite predictions, which can be tested by precision observation of fluctuations in the CMB, a program that is already well underway.

In this section, we will move beyond looking at inflation as a subject

of experimental test

and discuss some intriguing new ideas that indicate that inflation might

be useful as a tool

to illuminate physics at extremely high energies, possibly up to the

point where effects

from quantum gravity become relevant. This idea is based on a simple

observation about scales in the universe. As we discussed in

Sec. 2, quantum field theory extended to

infinitely high energy scales gives nonsensical (i.e., divergent)

results. We therefore

expect the theory to break down at high energy, or equivalently at very

short lengths. We

can estimate the length scale at which quantum mechanical effects from

gravity become

important by simple dimensional analysis. We define the Planck length

Pl

by an appropriate combination of fundamental constants as

Pl

by an appropriate combination of fundamental constants as

|

(133) |

For processes probing length scales shorter than

Pl, such as

quantum modes with wavelengths

Pl, such as

quantum modes with wavelengths

<

<

Pl, we expect

some sort of new physics to be important.

There are a number of ideas for what that new physics might be, for

example string theory

or noncommutative geometry or discrete spacetime, but physics at the

Planck scale is currently

not well understood. It is unlikely that particle accelerators will

provide insight into

such high energy scales, since quantum modes with wavelengths less than

Pl, we expect

some sort of new physics to be important.

There are a number of ideas for what that new physics might be, for

example string theory

or noncommutative geometry or discrete spacetime, but physics at the

Planck scale is currently

not well understood. It is unlikely that particle accelerators will

provide insight into

such high energy scales, since quantum modes with wavelengths less than

Pl will

be characterized by energies of order

1019 GeV or so, and current particle

accelerators operate at energies around 103 GeV.

(12)

However, we note an interesting

fact, namely that the ratio between the current horizon size of the

universe and the Planck length is about

Pl will

be characterized by energies of order

1019 GeV or so, and current particle

accelerators operate at energies around 103 GeV.

(12)

However, we note an interesting

fact, namely that the ratio between the current horizon size of the

universe and the Planck length is about

|

(134) |

or, on a log scale,

|

(135) |

This is a big number, but we recall our earlier discussion of the

flatness and horizon problems

and note that inflation, in order to adequately explain the flatness and

homogeneity of the

universe, requires the scale factor to increase by at least a

factor of e55. Typical

models of inflation predict much more expansion, e1000

or more. We remember that the

wavelength of quantum modes created during the inflationary expansion,

such as those responsible

for density and gravitational-wave fluctuations, have wavelengths which

redshift proportional to the scale factor, so that so that the

wavelength  i

of a mode at early times can be given in terms of its wavelength

i

of a mode at early times can be given in terms of its wavelength

0 today by

0 today by

|

(136) |

This means that if inflation lasts for more than about N ~ 140 e-folds, fluctuations of order the size of the universe today were smaller than the Planck length during inflation! This suggests the possibility that Plank-scale physics might have been important for the generation of quantum modes in inflation. The effects of such physics might be imprinted in the pattern of cosmological fluctuations we see in the CMB and large-scale structure today. In what follows, we will look at the generation of quantum fluctuations in inflation in detail, and estimate how large the effect of quantum gravity might be on the primordial power spectrum.

In Sec. 2.4 we saw that the state space for

a quantum field theory was a set of states

(n(k1), ..., n(ki))

representing the number of particles with momenta

k1,...,ki. The creation and annihilation

operators  †k and

†k and

k act on

these states by adding or subtracting a particle from the state:

k act on

these states by adding or subtracting a particle from the state:

|

(137) |

The ground state, or vacuum state of the space is just the zero particle state,

|

(138) |

Note in particular that the vacuum state |0> is not equivalent to zero. The vacuum is not nothing:

|

(139) |

To construct a quantum field, we look at the familiar classical wave equation for a scalar field,

|

(140) |

To solve this equation, we decompose into Fourier modes uk,

|

(141) |

where the mode functions uk(t) satisfy the ordinary differential equations

|

(142) |

This is a classical wave equation with a classical solution, and the Fourier coefficients ak are just complex numbers. The solution for the mode function is

|

(143) |

where  k

satisfies the dispersion relation

k

satisfies the dispersion relation

|

(144) |

To turn this into a quantum field, we identify the Fourier coefficients with creation and annihilation operators

|

(145) |

and enforce the commutation relations

|

(146) |

This is the standard quantization of a scalar field in Minkowski space, which should be familiar. But what probably isn't familiar is that this solution has an interesting symmetry. Suppose we define a new mode function uk which is a rotation of the solution (143):

|

(147) |

This is also a perfectly valid solution to the original wave

equation (140), since it is just a superposition of the Fourier

modes. But we can then re-write the quantum

field in terms of our original Fourier modes and new operators

k and

k and

†k and the original Fourier

modes eik . x as:

†k and the original Fourier

modes eik . x as:

|

(148) |

where the new operators

k are

given in terms of the old operators

k are

given in terms of the old operators

k by

k by

|

(149) |

This is completely equivalent to our original solution (141) as long as the new operators satisfy the same commutation relation as the original operators,

|

(150) |

This can be shown to place a condition on the coefficients A and B,

|

(151) |

Otherwise, we are free to choose A and B as we please.

This is just a standard property of linear differential equations: any

linear combination of

solutions is itself a solution. But what does it mean physically? In one

case, we have an annihilation operator

k which

gives zero when acting on a particular state which

we call the vacuum state:

k which

gives zero when acting on a particular state which

we call the vacuum state:

|

(152) |

Similarly, our rotated operator

k gives

zero when acting on some state

k gives

zero when acting on some state

|

(153) |

The point is that the two "vacuum" states are not the same

|

(154) |

From this point of view, we can define any state we wish to be the

"vacuum" and build a

completely consistent quantum field theory based on this

assumption. From another equally

valid point of view this state will contain particles. How do we tell

which is the

physical vacuum state? To define the real vacuum, we have to

consider the spacetime

the field is living in. For example, in regular special relativistic

quantum field theory,

the "true" vacuum is the zero-particle state as seen by an inertial

observer. Another

more formal way to state this is that we require the vacuum to be

Lorentz symmetric. This fixes our choice of vacuum

|0> and defines unambiguously our set of creation and annihilation

operators  and

and

†. A

consequence of this is that

an accelerated observer in the Minkowski vacuum will think that

the space is full of particles, a phenomenon known as the Unruh effect

[43].

The zero-particle state for an accelerated observer is different than

for an inertial observer.

†. A

consequence of this is that

an accelerated observer in the Minkowski vacuum will think that

the space is full of particles, a phenomenon known as the Unruh effect

[43].

The zero-particle state for an accelerated observer is different than

for an inertial observer.

So far we have been working within the context of field theory in special relativity. What about in an expanding universe? The generalization to a curved spacetime is straightforward, if a bit mysterious. We will replace the metric for special relativity with a Robertson-Walker metric,

|

(155) |

Note that we have written the Robertson-Walker metric in terms of

conformal time

d = dt/a.

This is convenient for doing field theory, because the new spacetime is

just a Minkowski

space with a time-dependent conformal factor out front. In fact we

define the physical vacuum

in a similar way to how we did it for special relativity: the vacuum is

the zero-particle

state as seen by a geodesic observer, that is, one in free-fall

in the expanding

space. This is referred to as the Bunch-Davies vacuum.

= dt/a.

This is convenient for doing field theory, because the new spacetime is

just a Minkowski

space with a time-dependent conformal factor out front. In fact we

define the physical vacuum

in a similar way to how we did it for special relativity: the vacuum is

the zero-particle

state as seen by a geodesic observer, that is, one in free-fall

in the expanding

space. This is referred to as the Bunch-Davies vacuum.

Now we write down the wave equation for a free field, the equivalent of Eq. (140) in a Robertson-Walker space. This is the usual equation with a new term that comes from the expansion of the universe:

|

(156) |

Note that the time derivatives are with respect to the conformal time

, not the coordinate

time t. As in the Minkowski case, we Fourier expand the field,

but with an extra factor

of a(

, not the coordinate

time t. As in the Minkowski case, we Fourier expand the field,

but with an extra factor

of a( ) in the integral:

) in the integral:

|

(157) |

Here k is a comoving wavenumber (or, equivalently, momentum),

which stays constant as the mode redshifts with the expansion

a, so that

a, so that

|

(158) |

Writing things this way, in terms of conformal time and comoving

wavenumber, makes the equation of motion for the mode

uk( )

very similar to the mode equation (142) in Minkowski space:

)

very similar to the mode equation (142) in Minkowski space:

|

(159) |

where a prime denotes a derivative with respect to conformal time. All

of the effect of the

expansion is in the a"/a term. (Be careful not to

confuse the scale factor

a( ) with

the creation/annihilation operators

) with

the creation/annihilation operators

k and

k and

†k!)

†k!)

This equation is easy to solve. First consider the short wavelength limit, that is large wavenumber k. For k2 >> a"/a, the mode equation is just what we had for Minkowski space

|

(160) |

except that we are now working with comoving momentum and conformal time, so the space is only quasi-Minkowski. The general solution for the mode is

|

(161) |

Here is where the definition of the vacuum comes in. Selecting the

Bunch-Davies vacuum is

equivalent to setting A = 1 and B = 0, so that the

annihilation operator is multiplied by

e-ik and

not some linear combination of positive and negative frequencies. This

is the exact analog of Eq. (147). So the mode function corresponding to

the zero-particle state for an observer in free fall is

and

not some linear combination of positive and negative frequencies. This

is the exact analog of Eq. (147). So the mode function corresponding to

the zero-particle state for an observer in free fall is

|

(162) |

What about the long wavelength limit, k2 << a"/a? The mode equation becomes trivial:

|

(163) |

with solution

|

(164) |

The mode is said to be frozen at long wavelengths, since the

oscillatory behavior is

damped. This is precisely the origin of the density and gravity-wave

fluctuations in inflation.

Modes at short wavelengths are rapidly redshifted by the inflationary

expansion so that the

wavelength of the mode is larger than the horizon size, Eq. (164). We

can plot the mode as a function of its physical wavelength

= k/a

divided by the horizon size dH = H-1

(Fig. 19), and find that at

long wavelengths, the mode freezes out to a nonzero value.

= k/a

divided by the horizon size dH = H-1

(Fig. 19), and find that at

long wavelengths, the mode freezes out to a nonzero value.

|

Figure 19. The mode function

uk / a as a function of

dH /

|

The power spectrum of fluctuations is just given by the two-point correlation function of the field,

|

(165) |

This means that we have produced classical perturbations at long wavelength from quantum fluctuations at short wavelength.

What does any of this have to do with quantum gravity? Remember that we

have seen that for

an inflationary period that lasts longer than 140 e-folds or so, the

fluctuations we see

with wavelengths comparable to the horizon size today started out with

wavelengths shorter than the Planck length

Pl ~

10-35 cm during inflation. For a mode with

a wavelength that short, do we really know how to select the "vacuum"

state, which we

have assumed is given by Eq. (162)? Not necessarily. We do know that once

the mode redshifts to a wavelength greater than

Pl ~

10-35 cm during inflation. For a mode with

a wavelength that short, do we really know how to select the "vacuum"

state, which we

have assumed is given by Eq. (162)? Not necessarily. We do know that once

the mode redshifts to a wavelength greater than

Pl, it must be of

the form (161), but we know longer know for certain how to select the values

of the constants A(k) and B(k). What we have

done is mapped the effect of quantum gravity onto

a boundary condition for the mode function

uk. In principle, A(k) and

B(k) could

be anything! If we allow A and B to remain arbitrary, it

is simple to calculate the

change in the two-point correlation function at long wavelength,

Pl, it must be of

the form (161), but we know longer know for certain how to select the values

of the constants A(k) and B(k). What we have

done is mapped the effect of quantum gravity onto

a boundary condition for the mode function

uk. In principle, A(k) and

B(k) could

be anything! If we allow A and B to remain arbitrary, it

is simple to calculate the

change in the two-point correlation function at long wavelength,

|

(166) |

where the subscript B-D indicates the value for the case of the "standard" Bunch-Davies vacuum, which corresponds to the choice A = 1, B = 0. So the power spectrum of gravity-wave and density fluctuations is sensitive to how we choose the vacuum state at distances shorter than the Planck scale, and is in principle sensitive to quantum gravity.

While in principle A(k) and B(k) are arbitrary, a great deal of recent work has been done implementing this idea within the context of reasonable toy models of the physics of short distances. There is some disagreement in the literature with regard to how big the parameter B can reasonably be. As one might expect on dimensional grounds, the size of the rotation is determined by the dimensionless ratio of the Planck length to the horizon size, so it is expected to be small

|

(167) |

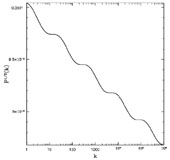

Here we have introduced a power p on the ratio, which varies depending on which model of short-distance physics you choose. Several groups have shown an effect linear in the ratio, p = 1. Fig. 20 shows the modulation of the power spectrum calculated in the context of one simple model [44].

|

Figure 20. Modulation of the power spectrum of primordial fluctuations for a rotation B ~ H/mPl. |

Others have argued that this is too optimistic, and that a more realistic estimate is p = 2 [45] or even smaller [46]. The difference is important: if p = 1, the modulation of the power spectrum can be as large as a percent or so, a potentially observable value [47]. Take p = 2 and the modulation drops to a hundredth of a percent, far too small to see. Nonetheless, it is almost certainly worth looking for!

12 This might not be so in "braneworld" scenarios where the energy scale of quantum gravity can be much lower [42]. Back.