B.10.1. An Analytic Model for Einstein Rings

Most of the lensed extended sources we see are dominated by an Einstein

ring - this occurs when the size of the source is comparable to the size

of the astroid caustic associated with producing four-image lenses.

When the Einstein ring is fairly thin, there

is a simple analytic model for the formation of Einstein rings

(Kochanek, Keeton & McLeod

[2001]).

The important point to understand is that the ring is a pattern rather

than a simple

combination of multiple images. Mathematically, what we identify as the

ring is the peak of the surface brightness as a function of angle around

the lens galaxy. We can identify the peak by finding the maximum

intensity  (

( )

along radial spokes in the image plane,

)

along radial spokes in the image plane,

(

( ) =

) =

0

+

0

+  (cos

(cos ,

sin

,

sin ). At

a given azimuth

). At

a given azimuth  we find the extremum of the surface brightness of the image

fD(

we find the extremum of the surface brightness of the image

fD( ) along each spoke, and these lie at the solutions of

) along each spoke, and these lie at the solutions of

|

(B.134) |

The next step is to translate the criterion for the ring location onto

the source plane. In real images, the observed image

fD( ) is related to the actual surface density

fI(

) is related to the actual surface density

fI( ) by a convolution with the beam (PSF),

fD(

) by a convolution with the beam (PSF),

fD( ) = B*

fI(

) = B*

fI( ), but for the moment we will

assume we are dealing with a true surface brightness map. Under this

assumption fD(

), but for the moment we will

assume we are dealing with a true surface brightness map. Under this

assumption fD( ) =

fI(

) =

fI( ) =

fS(

) =

fS( ) because of surface

brightness conservation. When we change variables, the criterion for the

peak brightness becomes

) because of surface

brightness conservation. When we change variables, the criterion for the

peak brightness becomes

|

(B.135) |

where the inverse magnification tensor M-1 =

d /

d

/

d is

introduced by the variable transformation. Geometrically we must find

the point where the tangent vector of the curve,

M-1 .

d

is

introduced by the variable transformation. Geometrically we must find

the point where the tangent vector of the curve,

M-1 .

d /

d

/

d is perpendicular to the local gradient of the surface brightness

is perpendicular to the local gradient of the surface brightness

fS(

fS( ). These steps are illustrated in

Fig. B.70.

). These steps are illustrated in

Fig. B.70.

This result is true in general but not very useful. We next assume that the

source has ellipsoidal surface brightness contours,

fS(m2), with m2 =

. S .

. S .

where

where

=

=  -

-  0 is the distance from the center of the source,

0 is the distance from the center of the source,

0,

and the matrix S is defined by the axis ratio

qs = 1 -

0,

and the matrix S is defined by the axis ratio

qs = 1 -

s

s

1 and position angle

1 and position angle

s of the

source. We must assume that the surface brightness declines

monotonically, dfs(m2) /

dm2 < 0, but require no

additional assumptions about the actual profile. With these assumptions

the Einstein ring curve is simply the solution of

s of the

source. We must assume that the surface brightness declines

monotonically, dfs(m2) /

dm2 < 0, but require no

additional assumptions about the actual profile. With these assumptions

the Einstein ring curve is simply the solution of

|

(B.136) |

The ring curve traces out a four (two) lobed cloverleaf pattern when

projected on the source plane if there are four (two) images of the

center of the source

(see Fig. B.70). These lobes touch the

tangential caustic at their maximum ellipsoidal distance from the source

center, and these cyclic variations

in the ellipsoidal radius produce the brightness variations seen around the

ring. The surface brightness along the ring is defined by

fI( (

( ),

),

)

for a spoke at azimuth

)

for a spoke at azimuth

and distance

and distance

(

( ) found by solving

Eqn. B.135. The extrema in the surface brightness around the ring are

located at the points where

) found by solving

Eqn. B.135. The extrema in the surface brightness around the ring are

located at the points where

fI(

fI( (

( ),

),

) = 0, which

occurs only at extrema

of the surface brightness of the source (the center of the source,

) = 0, which

occurs only at extrema

of the surface brightness of the source (the center of the source,

= 0 in the ellipsoidal model), or when the

ring crosses a critical line of the lens and the magnification tensor is

singular (| M|-1 = µ-1 = 0) for the

minima. These are general results that

do not depend on the assumption of ellipsoidal symmetry.

= 0 in the ellipsoidal model), or when the

ring crosses a critical line of the lens and the magnification tensor is

singular (| M|-1 = µ-1 = 0) for the

minima. These are general results that

do not depend on the assumption of ellipsoidal symmetry.

For an SIE lens in an external shear field we can derive some simple

properties of Einstein rings to lowest order in the various axis ratios.

Let the SIE have critical radius b, axis ratio

ql = 1 -

1 and put

its major axis along

1 and put

its major axis along

1. Let the

external shear have amplitude

1. Let the

external shear have amplitude

and

orientation

and

orientation

. We let

the source be an ellipsoid with axis ratio qs = 1 -

. We let

the source be an ellipsoid with axis ratio qs = 1 -

s

and a major axis angle

s

and a major axis angle

s located at

position (

s located at

position ( cos

cos 0,

0,

sin

sin 0)

from the lens center. The tangential critical line of the lens lies at

radius

0)

from the lens center. The tangential critical line of the lens lies at

radius

|

(B.137) |

while the Einstein ring lies at

|

(B.138) |

At this order, the Einstein ring is centered on the source position

rather than the lens position. The orientation of the ring is generally

perpendicular to that of the critical curve, although it need not be

exactly so when the SIE and the shear are misaligned due to the

differing coefficients of the shear and ellipticity terms in the two

expressions. These results lead to a false impression that the results

do not depend on the shape of the source. In making the expansion we

assumed that all the terms were of the same order

( / b ~

/ b ~

~

~

1 ~

1 ~

s),

but we are really doing an expansion in the ellipticity of the potential

of the lens

e

s),

but we are really doing an expansion in the ellipticity of the potential

of the lens

e ~

el / 3 rather than the ellipticity of the density

distribution

of the lens, so second order terms in the shape of the source are as

important as first order terms in the ellipticity of the potential. For

example in a circular lens with no shear

(

~

el / 3 rather than the ellipticity of the density

distribution

of the lens, so second order terms in the shape of the source are as

important as first order terms in the ellipticity of the potential. For

example in a circular lens with no shear

( 1 = 0,

1 = 0,

= 0) the

ring is located at

= 0) the

ring is located at

|

(B.139) |

which has only odd terms in its multipole expansion and converges slowly for flattened sources. In general, the ring shape is a weak function of the source shape only if the potential is nearly round and the source is almost centered on the lens. The structure of the lens potential dominates the even multipoles of the ring shape, while the structure of the source dominates the odd multipoles.

In fact, the shape of the ring can be used to simply "read off" the

amplitudes of the higher order multipoles of the lens potential. This is

nicely illustrated by an isothermal potential with arbitrary angular

structure,  =

rbF(

=

rbF( ) with

<F(

) with

<F( )>

= 1 (see Zhao & Pronk

[2001],

Witt et al.

[2000],

Kochanek et al.

[2001],

Evans & Witt

[2001])

in the absence of any shear. The tangential critical line of the lens is

)>

= 1 (see Zhao & Pronk

[2001],

Witt et al.

[2000],

Kochanek et al.

[2001],

Evans & Witt

[2001])

in the absence of any shear. The tangential critical line of the lens is

|

(B.140) |

If

and

and

are

radial and tangential unit vectors relative to the lens center and

are

radial and tangential unit vectors relative to the lens center and

0 is the distance of the source from

the lens center, then the Einstein ring curve is

0 is the distance of the source from

the lens center, then the Einstein ring curve is

|

(B.141) |

with the limit showing the result for a circular source.

Thus, by analyzing

the multipole structure of the ring curve one can deduce the multipole

structure of the potential. While this has not been done

non-parametrically, the ability of standard ellipsoidal models to

reproduce ring curves strongly suggests that higher order multipoles

cannot be significantly different from the ellipsoidal

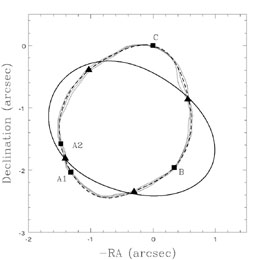

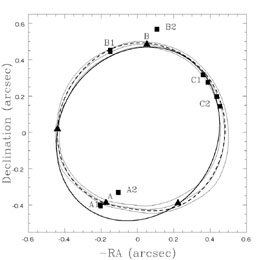

scalings. Fig. B.71 shows two examples of fits

to the ring curves

in PG1115+080 and B1938+666 using SIE plus external shear lens models. The

major systematic problem with fitting the real data are that bright

quasar images

must frequently be subtracted from the image before the ring curve can be

extracted, and this can lead to artifacts like the wiggle in the curve

between the bright A1 / A2 images of

PG1115+080. Other than that, the

accuracy with which the ellipsoidal (plus shear) models reproduce the curves

is consistent with the uncertainties. In both cases the host galaxy is

relatively flat (qs = 0.58 ± 0.02 for PG1115+080 and 0.62 ± 0.14 for

B1938+666). The flatness of the host explains the

"boxiness" of the

PG1115+080 ring, while the B1938+666 host galaxy shape is poorly constrained

because the center of the host is very close to the center of the lens

galaxy so the shape of the ring is insensitive to the shape of the source.

Unless the source is significantly offset from the center of the lens,

as we might see for the host galaxy of an asymmetric two-image lens, it

does not constrain the radial density profile of the lens very well -

after considerable algebraic effort you can show that the dependence on the

radial structure scales as

|

|4. It can, however, help

considerably in this circumstance because it eliminates the angular degrees

of freedom in the potential that make it impossible for two-image lenses

to constrain the radial density profile at all.

|4. It can, however, help

considerably in this circumstance because it eliminates the angular degrees

of freedom in the potential that make it impossible for two-image lenses

to constrain the radial density profile at all.

|

|

Figure B.71. The Einstein ring curves in PG1115+080 (top) and B1938+666 (bottom). The black squares mark the lensed quasar or compact radio sources. The light black lines show the ring curve and its uncertainties. The black triangles show the intensity minima along the ring curve (but not their uncertainties). The best fit model ring curve is shown by the dashed curve, and the heavy solid curve shows the critical line of the best fit model. The model was not constrained to fit the critical line crossings. |