Since hydrogen is the most abundant element in stars and galaxies we might expect that its distribution across a galaxy provides information relevant for the theories of galactic evolution. A very simple theory of the chemical evolution of galaxies (Searle and Sargent, 1972) predicts that the abundance of a heavy element in a given volume element depends on the ratio of total mass to gas mass in the following way:

|

(1) |

the yield is the ratio of the rate at which heavy elements are

produced by nucleosynthesis and ejected into the interstellar gas

to the net rate at which hydrogen is removed from the interstellar

gas by star formation. More elaborate theories, like those of

Talbot and Arnett (1975),

Lynden-Bell (1975)

and those outlined by

Audouze and Tinsley (1976),

predict similar relationships between

these quantities. If radial mixing is not too important inside a

galaxy we can replace the ratio total mass to gas mass by the

ratio of local mass surface densities:

M(R) and

M(R) and

G(R)

for mass

and gas mass respectively. Not much is known about the average

yield (the average is a time average from t = 0 until the present

epoch). In principle we can obtain information on the abundances

from the line strength ratios in HII regions at different radii; the ratio

G(R)

for mass

and gas mass respectively. Not much is known about the average

yield (the average is a time average from t = 0 until the present

epoch). In principle we can obtain information on the abundances

from the line strength ratios in HII regions at different radii; the ratio

M(R)

/

M(R)

/  G(R)

can, to some extent, be estimated from 21-cm

line observations. In this section we present some information on

G(R)

can, to some extent, be estimated from 21-cm

line observations. In this section we present some information on

M(R)

/

M(R)

/  HI(R),

where

HI(R),

where

HI(R) is

the mass surface density of neutral hydrogen, and we compare these

results with available data on line strength ratios.

HI(R) is

the mass surface density of neutral hydrogen, and we compare these

results with available data on line strength ratios.

For 14 galaxies in our sample the radial distribution of an,

has been determined from the 21 cm maps by averaging in annuli

over the azimuthal direction. The width of these annuli is usually

taken to be the size of the synthesized beam. We have corrected to

face-on values by a multiplication with the cosine of the

inclination. Note that these results are not corrected for optical depth

effects. As in the case of rotation curves, also the determination of

HI(R)

is hampered by the presence of deviations from

axial symmetry in spiral galaxies; for each type of deviation we have

followed the same procedures as in the case of rotation curves (see

chapter 6). Even more serious is the

beamsmoothing in the central parts, and this results in practice in an

overestimate of

HI(R)

is hampered by the presence of deviations from

axial symmetry in spiral galaxies; for each type of deviation we have

followed the same procedures as in the case of rotation curves (see

chapter 6). Even more serious is the

beamsmoothing in the central parts, and this results in practice in an

overestimate of

HI in the

centre (cf. chapter 3). The results for

HI in the

centre (cf. chapter 3). The results for

M(R)

/

M(R)

/  HI(R)

are, obviously, even more uncertain.

HI(R)

are, obviously, even more uncertain.

In Fig. 7 we present the curves of

M(R)

/

M(R)

/  HI(R)

for various

galaxies. The curves can be divided in two parts: a gradually declining

inner part and a roughly flat outer part. For the galaxies with

large scale asymmetries this outer part is actually not reached. In

addition to the deviations from axial symmetry another problem arises

here: for nearly face-on galaxies the inclination correction for the

velocities is large and hence

HI(R)

for various

galaxies. The curves can be divided in two parts: a gradually declining

inner part and a roughly flat outer part. For the galaxies with

large scale asymmetries this outer part is actually not reached. In

addition to the deviations from axial symmetry another problem arises

here: for nearly face-on galaxies the inclination correction for the

velocities is large and hence

M is

uncertain. This problem is illustrated for the case of M51 in

Fig. 7b. The lower curve

of M51 is based on an inclination of 35° (the one

adopted by

Segalovitz, 1976),

the upper curve is based on an inclination of 20° (cf.

Tully, 1974).

M is

uncertain. This problem is illustrated for the case of M51 in

Fig. 7b. The lower curve

of M51 is based on an inclination of 35° (the one

adopted by

Segalovitz, 1976),

the upper curve is based on an inclination of 20° (cf.

Tully, 1974).

|

Figure 7. Radial variation of the total

mass to HI gas mass surface density ratio in various galaxies.

|

The contributions of gaseous components other than HI to

G(R)

are unknown. For our Galaxy an estimate for the contribution of

G(R)

are unknown. For our Galaxy an estimate for the contribution of

H to

H to

G can be

derived from the CO observations (see

Gordon and Burton, 1976).

The lack of knowledge about the conversion

factor from CO-abundance to H2 abundance, however, makes such an

estimate uncertain.

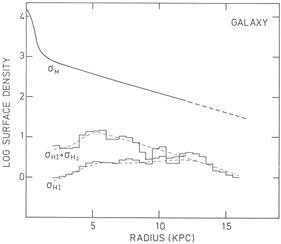

In Fig. 8 we present the variation in

G can be

derived from the CO observations (see

Gordon and Burton, 1976).

The lack of knowledge about the conversion

factor from CO-abundance to H2 abundance, however, makes such an

estimate uncertain.

In Fig. 8 we present the variation in

M(R),

M(R),

HI(R)

and

HI(R)

and  H2(R) in our

Galaxy. Since HI and H2 are the main contributors to the gas

mass we tentatively conclude that

H2(R) in our

Galaxy. Since HI and H2 are the main contributors to the gas

mass we tentatively conclude that

M /

M /

G is roughly

constant beyond R = 5 kpc.

Note that the contribution of H2 dominates in the inner

parts. In our

Galaxy there is a fair agreement between the radial distributions of

molecules and of HII regions, but the HI extends much farther out

(cf. Burton, 1976).

In external galaxies the radial distribution of

HII-regions is also more concentrated to the inner parts than is

the HI distribution It might be conjectured that, similar to our

Galaxy, the ratio of

G is roughly

constant beyond R = 5 kpc.

Note that the contribution of H2 dominates in the inner

parts. In our

Galaxy there is a fair agreement between the radial distributions of

molecules and of HII regions, but the HI extends much farther out

(cf. Burton, 1976).

In external galaxies the radial distribution of

HII-regions is also more concentrated to the inner parts than is

the HI distribution It might be conjectured that, similar to our

Galaxy, the ratio of

M(R)

/

M(R)

/  G(R)

remains more or less constant

beyond about one-third of the optical radius, but we must again

emphasize that the uncertainty in the contribution of

G(R)

remains more or less constant

beyond about one-third of the optical radius, but we must again

emphasize that the uncertainty in the contribution of

H2

to

H2

to

G is quite large.

G is quite large.

|

Figure 8. Radial variation of mass and gas

mass surface densities in our Galaxy. The histograms are adapted from

Gordon and Burton (1976).

The dashed lines have been used to calculate the

|

b) Variation of

M /

M /

G with type

and size

G with type

and size

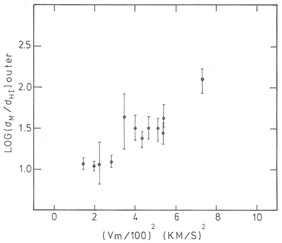

We assume for the moment that the ratio

M(R)

/

M(R)

/  G(R)

is indeed constant in the outer parts of galaxies and that

G(R)

is indeed constant in the outer parts of galaxies and that

G(R) is

dominated there by

G(R) is

dominated there by

HI(R).

The value of this ratio seems to correlate with Vm,

as can be seen in Fig. 9. Two difficulties arise

in the interpretation of this figure: 1) the inclination, and therefore

HI(R).

The value of this ratio seems to correlate with Vm,

as can be seen in Fig. 9. Two difficulties arise

in the interpretation of this figure: 1) the inclination, and therefore

M, might be

in error for the nearly face-on galaxies; 2) part of the mass may

not be distributed in a disk. If these difficulties are not too

important, we conclude that galaxies with large Vm

have a high

M, might be

in error for the nearly face-on galaxies; 2) part of the mass may

not be distributed in a disk. If these difficulties are not too

important, we conclude that galaxies with large Vm

have a high  M /

M /

G

in the outer parts, while galaxies with smaller Vm

have a low

G

in the outer parts, while galaxies with smaller Vm

have a low  M /

M /

G.

G.

|

Figure 9. Mass to gas mass ratio,

|

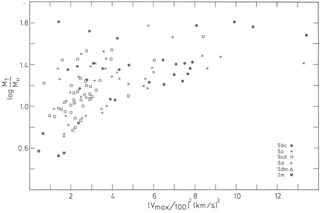

Because our sample is small, we do not know whether the correlation in

Fig. 9 is a chance coincidence. We can, however,

test this correlation by noting that, if

M /

M /

HI is

constant, the integrated values

MT / MH should also give us to some

extent the value of this constant. In Fig. 10

we present the values of

MT / MH as function of

Vo, the halfwidth of the 21 cm integral profile, for the sample of

galaxies discussed by

Shostak (1978).

MT / MH in this case is derived

from integral properties, and is therefore not entirely comparable

with the

HI is

constant, the integrated values

MT / MH should also give us to some

extent the value of this constant. In Fig. 10

we present the values of

MT / MH as function of

Vo, the halfwidth of the 21 cm integral profile, for the sample of

galaxies discussed by

Shostak (1978).

MT / MH in this case is derived

from integral properties, and is therefore not entirely comparable

with the

M

/

M

/  HI

discussed above. Nevertheless, it is clear that

there are no galaxies with high Vo and, low

MT / MH. This result also

indicates that in galaxies with high Vm the gas to

mass ratio is lower than in galaxies with low Vm.

HI

discussed above. Nevertheless, it is clear that

there are no galaxies with high Vo and, low

MT / MH. This result also

indicates that in galaxies with high Vm the gas to

mass ratio is lower than in galaxies with low Vm.

|

Figure 10. Total mass to hydrogen mass ratio vs Vo (half the width of the HI profile divided by sin i) from single dish data by Shostak (1978). |

In the inner parts of galaxies the reliability of the data on

M

/

M

/  HI is even

poorer than in the outer parts

because of the beam-smoothing effects, but there is a trend that

HI is even

poorer than in the outer parts

because of the beam-smoothing effects, but there is a trend that

M /

M /

HI in the central

region is much larger in earlier type spirals than in later types.

In galaxies with bulges no HI emission has been detected, the upper

limit to the surface density of HI is about

1.0M

HI in the central

region is much larger in earlier type spirals than in later types.

In galaxies with bulges no HI emission has been detected, the upper

limit to the surface density of HI is about

1.0M pc-2. Several explanations may be given to account for this:

pc-2. Several explanations may be given to account for this:

1) The absence of HI in galaxies with bulges is reminiscent to the lack of HI in elliptical galaxies. Perhaps a hot galactic wind is present which keeps the bulge clean of the gas shed from evolving stars (see Faber and Gallagher, 1976).

2) Star formation might play an important role too, but it is not clear

which mechanism is responsible for star formation. The fashionable idea

that the star formation is triggered by (stationary Lin-Shu) density waves

(cf. Oort, 1974;

Jensen, Strom and Strom,

1976)

might not be adequate to explain the constant value of

M

/

M

/  G

in our Galaxy if the star formation

rate is proportional to the difference in angular velocity of the

gas and that of the wave i.e. proportional to

(

G

in our Galaxy if the star formation

rate is proportional to the difference in angular velocity of the

gas and that of the wave i.e. proportional to

( -

-

p). This

mechanism seems also inadequate to explain the absence of gas in the

central parts of the multi-armed spiral NGC 2841 (cf.

chapter 4.6).

p). This

mechanism seems also inadequate to explain the absence of gas in the

central parts of the multi-armed spiral NGC 2841 (cf.

chapter 4.6).

3) For later type galaxies, which have a higher content of

population I material, the contribution of molecules may be so high

that  M /

M /

G remains

constant even though

G remains

constant even though

M /

M /

HI is

increasing towards

the centre. Quantitative estimates of the contribution of molecules

to

HI is

increasing towards

the centre. Quantitative estimates of the contribution of molecules

to  G in these

galaxies are necessary to test this possibility.

G in these

galaxies are necessary to test this possibility.

c) Comparison with abundance determinations

For a few galaxies data are available on the strength of the

emission lines of several HII regions (see review by

Webster, 1977).

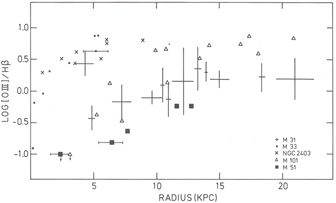

In Fig. 11 we have presented the data on log

[OIII] /

H versus radius

for five galaxies in our sample, taken from

Smith (1975) and

Rubin, Kumar and Ford

(1972)

(we have averaged the data of Rubin et al. by

taking means of 4 points at adjacent radii). This line strength ratio

increases with radius. Various theoretical studies indicate that

this, and similar systematic radial variations in other line strength

ratios, can be explained by a decrease of the heavy element abundance

with radius

(Searle, 1971;

Shields and Tinsley, 1976;

Sarazin, 1976).

Recently

Churchwell et al. (1977)

reported a systematic variation of

the temperature of galactic HII regions across the Galaxy which they

interpret as due to an abundance gradient; this result may not be

significant in view of the complications in the analysis of radio

recombination line data (cf.

Lockman and Brown, 1978).

Although the

amplitude of the abundance gradients depends almost entirely on the

assumed HII region models, most authors seem to agree that such

gradients exist.

versus radius

for five galaxies in our sample, taken from

Smith (1975) and

Rubin, Kumar and Ford

(1972)

(we have averaged the data of Rubin et al. by

taking means of 4 points at adjacent radii). This line strength ratio

increases with radius. Various theoretical studies indicate that

this, and similar systematic radial variations in other line strength

ratios, can be explained by a decrease of the heavy element abundance

with radius

(Searle, 1971;

Shields and Tinsley, 1976;

Sarazin, 1976).

Recently

Churchwell et al. (1977)

reported a systematic variation of

the temperature of galactic HII regions across the Galaxy which they

interpret as due to an abundance gradient; this result may not be

significant in view of the complications in the analysis of radio

recombination line data (cf.

Lockman and Brown, 1978).

Although the

amplitude of the abundance gradients depends almost entirely on the

assumed HII region models, most authors seem to agree that such

gradients exist.

|

Figure 11. Radial variation of the [OIII] /

H |

If such gradients are indeed present, and if the constancy of

M /

M /

G is also

accepted, we must conclude from equation (1) that the

mean yield is decreasing with radius. Thus, the amount of heavy

elements shed from stars into the interstellar medium compared to

the star formation rate must be lower in the outer parts of

galaxies. This suggests that the mass function of stars is a function of

radius; in the outer parts there are fewer massive stars (which

produce more metals in a shorter time than do dwarfs). Note that

this result is consistent with an increase in the mass-to-luminosity

ratio with distance to the centre.

G is also

accepted, we must conclude from equation (1) that the

mean yield is decreasing with radius. Thus, the amount of heavy

elements shed from stars into the interstellar medium compared to

the star formation rate must be lower in the outer parts of

galaxies. This suggests that the mass function of stars is a function of

radius; in the outer parts there are fewer massive stars (which

produce more metals in a shorter time than do dwarfs). Note that

this result is consistent with an increase in the mass-to-luminosity

ratio with distance to the centre.

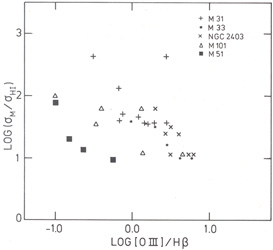

We can also compare the abundance variations among different

galaxies with the mass to gas mass ratio. In

Fig. 12 we have plotted

log [OIII] / H versus log

versus log

M /

M /

HI for

various locations in a number of

galaxies. This plot is more difficult to interpret than

Fig. 11.

Various assumptions are necessary to convert log [OIII] /

H

HI for

various locations in a number of

galaxies. This plot is more difficult to interpret than

Fig. 11.

Various assumptions are necessary to convert log [OIII] /

H into an

abundance ratio and

into an

abundance ratio and

M /

M /

HI is in the

inner parts not equal to

HI is in the

inner parts not equal to

M /

M /

G.

Further, we are probably dealing with an atypical sample of galaxies:

in both M51 and M101 large scale asymmetries occur which make the

determination of

G.

Further, we are probably dealing with an atypical sample of galaxies:

in both M51 and M101 large scale asymmetries occur which make the

determination of

M(r)

difficult. If we restrict ourselves

to NGC 2403, M33 and M31 we find that, apart from anomalous inner HII

regions in M31, a loose correlation exists. The inner parts of

M33 and NGC 2403 have about the same linestrength ratio and

HI-gas mass to total mass ratio as the outer parts of M31. The mass-to-luminosity

ratios in these regions are, however, very different: in the inner

parts of M33 and NGC 2403

M(r)

difficult. If we restrict ourselves

to NGC 2403, M33 and M31 we find that, apart from anomalous inner HII

regions in M31, a loose correlation exists. The inner parts of

M33 and NGC 2403 have about the same linestrength ratio and

HI-gas mass to total mass ratio as the outer parts of M31. The mass-to-luminosity

ratios in these regions are, however, very different: in the inner

parts of M33 and NGC 2403

M

/

M

/  LB

LB

3, and in the outer

parts (10-20 kpc) of M31 it is about 18. In the outer parts of M31 the abundance

of oxygen is about 6 times higher than in the outer parts of M33 (we

have used the conversion plot for log [OIII] /

H

3, and in the outer

parts (10-20 kpc) of M31 it is about 18. In the outer parts of M31 the abundance

of oxygen is about 6 times higher than in the outer parts of M33 (we

have used the conversion plot for log [OIII] /

H

[O/H] given by

Sarazin (1976)).

Since the ratios of log

[O/H] given by

Sarazin (1976)).

Since the ratios of log

M /

M /

HI in these

regions differ by only 1.5 we conclude that the yield in the outer parts of

M31 must have been higher than in the outer parts of

its companion M33. From the comparison of data on our Galaxy, NGC 6822, and the

Magellanic Clouds, however, (see

Lynden-Bell, 1975,

Fig. 1) we find

that the, yield must be higher in the dwarf galaxies than in the

solar neighbourhood. Apparently there is no simple relation between

the yield and a parameter like Vm, which scales with

the mass of a

galaxy. There is also hardly any correlation between the line

strength ratio and morphological type, as can be seen from

Fig. 10. Also the results for NGC 6503 and NGC 2403, both Scd III galaxies, obtained by

Jensen et al. (1976)

show a large difference in line

strength ratio. Hence not much can be concluded from these data

with regard to the yield in different galaxies.

HI in these

regions differ by only 1.5 we conclude that the yield in the outer parts of

M31 must have been higher than in the outer parts of

its companion M33. From the comparison of data on our Galaxy, NGC 6822, and the

Magellanic Clouds, however, (see

Lynden-Bell, 1975,

Fig. 1) we find

that the, yield must be higher in the dwarf galaxies than in the

solar neighbourhood. Apparently there is no simple relation between

the yield and a parameter like Vm, which scales with

the mass of a

galaxy. There is also hardly any correlation between the line

strength ratio and morphological type, as can be seen from

Fig. 10. Also the results for NGC 6503 and NGC 2403, both Scd III galaxies, obtained by

Jensen et al. (1976)

show a large difference in line

strength ratio. Hence not much can be concluded from these data

with regard to the yield in different galaxies.

|

Figure 12. Comparison of LOIIIJ/HS ratios and

|

We have presented the above discussion to illustrate the complexity of

the problems we encounter if a simple relation between

the abundances of heavy elements and the total mass to gas mass ratio,

like equation (1), is to be tested. It is very difficult to

draw any conclusions from this discussion other than the obvious

one that the uncertainties are large. We find, however, some interesting

correlations suggesting a variation of the mass function

with radius. No clear relationship exists between the line strength

ratio log [OIII] /

H and type or

size of a galaxy.

and type or

size of a galaxy.