Hundreds of years ago, we inhabited a dwarf Universe consisting of planets and limited by a sphere of fixed stars (Fig. 1). One hundred years ago, the concept of the Universe consisting entirely of stars dominated. That Universe appeared as a huge oblate star cluster, the Milky Way, with the Sun located close to its center. At the beginning of the third millennium, the volume of the Universe available to astronomical observations includes hundreds of billions of `recessing' galaxies (Fig. 18 3), surrounded by dark matter halos and embedded in an anti-gravitating cosmic vacuum [144]. Our Universe has already passed its peak activity and we are living in its history of `decline' when the epoch of active star formation has already ended and galaxies have recessed from each other and only relatively rarely interact with each other.

|

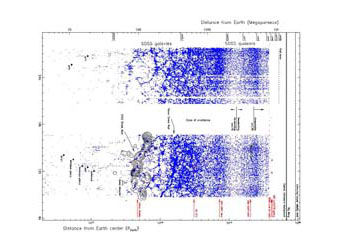

Figure 18. The map of the Universe

[143].

An equatorial slice

(-2° < |

The sky surveys and selected deep field studies, some of which have been discussed in this review, play a very important role in creating a large-scale picture of the world. Modern sky surveys provide information on the characteristics and spatial distribution of millions of galaxies. Deep fields allow galaxies under formation and their evolution over billions of years to be studied. According to some researchers, should the current progress in observations be continued, the question of the formation and evolution of galaxies will be answered in one or two decades. At that time, we might "look back to this one and recall with nostalgia how exciting it was to help write that story" [145].

The wealth of observational data obtained by the projects described in this review has already been counted in dozens of terabytes. These data, as a rule, are freely accessible and can be used through the world-wide web by both professional researchers and amateurs. All major ground-based telescopes and space observatories also have data archives where results of observations are stored (the BTA observations archive can be found at http://www.sao.ru).

The huge available amount of information on the Universe has altered the face of modern astronomy. The current rate of observational data storage on astronomy has reached ~ 1 TB/day [146]. Many important tasks, from statistical studies of the Milky Way and studies of the large-scale distribution of galaxies to the discovery of new types of objects, can now be solved without additional observations by telescopes. These new possibilities, which often escape the attention of even professional astronomers, pose `technological' problems, such as rapid and convenient access to world-wide dispersed and often inhomogeneous data, their visualization and analysis, etc. This has stimulated the appearance of the Virtual Observatory concept (http://www.ivoa.net) primarily aimed at increasing the efficiency of astronomical studies under conditions of a colossal amount of information [146]. Modern and future multi-wavelength sky surveys create a kind of `virtual Universe' in our computers, and the Virtual Observatory may turn out to be the principal tool for its investigation.

This work is supported by the RFBR grant 03-02-17152.

3 It is instructive to note a certain visual similarity between Fig. 18 and Fig. 1. Back.