This section is somewhat pedagogical in nature, containing a brief summary of the work of Bondi, Hoyle and Lyttleton. Readers familiar with the basic nature of Bondi-Hoyle-Lyttleton accretion may wish to skip this section.

2.1. The Analysis of Hoyle & Lyttleton

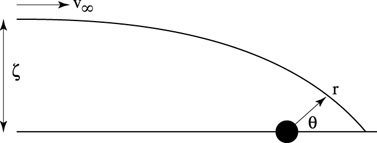

Hoyle and Lyttleton (1939) considered accretion by a star moving at a steady speed through an infinite gas cloud. The gravity of the star focuses the flow into a wake which it then accretes. The geometry is sketched in figure 1.

|

Figure 1. Sketch of the Bondi-Hoyle-Lyttleton accretion geometry |

Hoyle and Lyttleton derived the accretion rate in the following manner:

Consider a streamline with impact parameter

.

If this follows a ballistic orbit (it will if pressure effects are

negligible), then we can apply conventional orbit theory. We have

.

If this follows a ballistic orbit (it will if pressure effects are

negligible), then we can apply conventional orbit theory. We have

|

(1) (2) |

in the radial and polar directions respectively.

Note that the second equation expresses the conservation

of angular momentum.

Setting h =  v

v and making the usual

substitution u = r-1, we may rewrite the first

equation as

and making the usual

substitution u = r-1, we may rewrite the first

equation as

|

(3) |

The general solution is u = A

cos + B

sin

+ B

sin + C

for arbitrary constants A, B and C.

Substitution of this general solution immediately shows that

C = GM / h2.

The values of A and B are fixed by the boundary conditions

that u

+ C

for arbitrary constants A, B and C.

Substitution of this general solution immediately shows that

C = GM / h2.

The values of A and B are fixed by the boundary conditions

that u  0

(that is, r

0

(that is, r

) as

) as

, and that

, and that

|

These will be satisfied by

|

(4) |

Now consider when the flow encounters the

= 0 axis.

As a first approximation, the

= 0 axis.

As a first approximation, the

velocity will go to zero

at this point. The radial velocity will be

v

velocity will go to zero

at this point. The radial velocity will be

v and the radius of

the streamline will be given by

and the radius of

the streamline will be given by

|

(5) |

Assuming that material will be accreted if it is bound to the star we have

|

or

|

(6) |

which defines the critical impact parameter, known as the Hoyle-Lyttleton radius. Material with an impact parameter smaller than this value will be accreted. The mass flux is therefore

|

(7) |

which is known as the Hoyle-Lyttleton accretion rate.

The Hoyle-Lyttleton analysis contains no fluid effects, which makes it ripe for analytic solution. This was performed by Bisnovatyi-Kogan et al. (1979), who derived the following solution for the flow field:

|

(8) (9) (10) (11) |

The first three equations are fairly straightforward, and follow (albeit tediously) from the orbit solution given above. The equation for the density is rather less pleasant, and involves solving the steady state gas continuity equation under conditions of axial symmetry.

Equation 4 may be rewritten into the form

|

(12) |

where e is the eccentricity of the orbit, r0 is

the semi-latus rectum, and

0 is the

periastron angle. These quantities may be expressed as

0 is the

periastron angle. These quantities may be expressed as

|

(13) (14) (15) |

which may be useful as an alternative form to equation 10.

Note that these equations do not follow material down to the accretor.

Accretion is assumed to occur through an infinitely thin, infinite density

column on the  = 0 axis.

This is not physically consistent with the ballistic assumption, since

it would not be possible to radiate away the thermal energy released

as the material loses its

= 0 axis.

This is not physically consistent with the ballistic assumption, since

it would not be possible to radiate away the thermal energy released

as the material loses its

velocity.

Even with a finite size for the accretion column, a significant trapping

of thermal energy would still be expected.

For now we shall neglect this effect.

velocity.

Even with a finite size for the accretion column, a significant trapping

of thermal energy would still be expected.

For now we shall neglect this effect.

2.3. The Analysis of Bondi and Hoyle

Bondi and

Hoyle (1944)

extended the analysis to include

the accretion column (the wake following the point mass on the

= 0 axis).

We will now follow their reasoning, and show that this suggests

that the accretion rate could be as little as half the value

suggested in equation 7.

Figure 2 sketches the quantities we shall use.

= 0 axis).

We will now follow their reasoning, and show that this suggests

that the accretion rate could be as little as half the value

suggested in equation 7.

Figure 2 sketches the quantities we shall use.

|

Figure 2. Sketch of the geometry for the Bondi-Hoyle analysis |

From the orbit equations, we know that material encounters

the  = 0 axis at

= 0 axis at

|

This means that the mass flux arriving in the distance r to r + dr is given by

|

(16) |

which defines  .

Note that it is independent of r.

The transverse momentum flux in the same interval is given by

.

Note that it is independent of r.

The transverse momentum flux in the same interval is given by

|

which is the mass flux, multiplied by the transverse velocity, divided over the approximate area of the wake. Applying the orbit equations once more, and noting that a momentum flux is the same as a pressure, we find

|

(17) |

as an estimate of the pressure in the wake. The longitudinal pressure force is therefore

|

Material will take a time of about r /

v to fall onto the

accretor from the point it encounters the axis.

This means that we can use the accretion rate to estimate the mass

per unit length of the wake, m, as

to fall onto the

accretor from the point it encounters the axis.

This means that we can use the accretion rate to estimate the mass

per unit length of the wake, m, as

|

(18) |

This makes the gravitational force per unit length

|

For accreting material, we must have r ~ G M

v -2.

If we also assume that the wake is thin (s

<< r) and roughly conical (ds / s

-2.

If we also assume that the wake is thin (s

<< r) and roughly conical (ds / s

dr /

r), then

taking the ratio of the pressure and gravitational forces, we find

that pressure force is much less than the gravitational force.

We can therefore neglect the gas pressure in the wake.

dr /

r), then

taking the ratio of the pressure and gravitational forces, we find

that pressure force is much less than the gravitational force.

We can therefore neglect the gas pressure in the wake.

The mass per unit length of the wake, m, was introduced above. If we assume the mean velocity in the wake is v, we can write two conservation laws, for mass and momentum:

|

(19) (20) |

Recall that  v

v is the momentum supply

into the wake, since r =

v

is the momentum supply

into the wake, since r =

v on axis for all streamlines.

We can declutter these equations by introducing dimensionless

variables for m, r and v:

on axis for all streamlines.

We can declutter these equations by introducing dimensionless

variables for m, r and v:

|

(21) (22) (23) |

Note that  =

2 corresponds to material arriving from the streamline

characterised by

=

2 corresponds to material arriving from the streamline

characterised by

HL.

Substituting these definitions into equations 19 and 20, we obtain

HL.

Substituting these definitions into equations 19 and 20, we obtain

|

(24) (25) |

We shall now analyse the behaviour of these equations.

We can integrate equation 24 to yield

|

(26) |

for some constant  .

Since µ is a scaled mass (and hence always positive), we see

that the scaled velocity

(

.

Since µ is a scaled mass (and hence always positive), we see

that the scaled velocity

( ) changes sign when

) changes sign when

=

=

.

That is,

.

That is,  is the

stagnation point.

Material for

is the

stagnation point.

Material for  <

<  will accrete, so knowing

will accrete, so knowing

will

tell us the accretion rate (since the accretion rate will be

will

tell us the accretion rate (since the accretion rate will be

r0

where r0 is the value of r

corresponding to

r0

where r0 is the value of r

corresponding to  ).

By writing

µ

).

By writing

µ 2 =

µ

2 =

µ ·

·

, we can use

equation 26 to rewrite equation 25 as

, we can use

equation 26 to rewrite equation 25 as

|

(27) |

This has not obviously improved matters, but we can now study the general behaviour of the function, without trying to solve it. First we need some boundary conditions. These are as follows:

1 as

1 as

v

v at large radii

at large radii

= 0 at

= 0 at

=

=

/

d

/

d > 0 Everywhere

> 0 Everywhere

The velocity must be a monotonic function. This is physically reasonable, if we are to avoid unusual flow patterns

The first two conditions can be satisfied for any value of

.

Fortunately, the third implies as restriction.

The next set of manipulations may seem a little obscure at first, but

they do lead in the desired direction.

.

Fortunately, the third implies as restriction.

The next set of manipulations may seem a little obscure at first, but

they do lead in the desired direction.

Substitute  =

=

-1

-1

.

Equation 27 then reads

.

Equation 27 then reads

|

(28) |

Now, suppose the derivative is zero. This leads to the condition

|

or, one application of the quadratic roots formula later:

|

(29) |

Since  ultimately represents a

physical quantity (the velocity), it's obviously desirable that it

remain real. We therefore need to look at when the discriminant can

become zero. This is another quadratic equation, leading to

ultimately represents a

physical quantity (the velocity), it's obviously desirable that it

remain real. We therefore need to look at when the discriminant can

become zero. This is another quadratic equation, leading to

|

which means that something must happen when

= 1.

To determine this `something,' it is best to plot equation 29.

= 1.

To determine this `something,' it is best to plot equation 29.

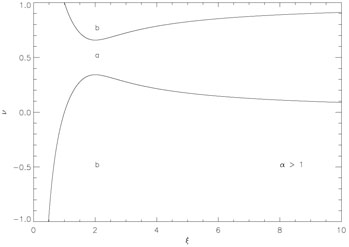

Figures 3 and 4

demarcate the regions where d / d

/ d changes

sign, as dictated by equation 29. These are not possible

solutions for

changes

sign, as dictated by equation 29. These are not possible

solutions for  .

However, any suitable solution for

.

However, any suitable solution for

must remain within

the region marked `a' if it is to remain monotonic and increasing.

This is only possible when

must remain within

the region marked `a' if it is to remain monotonic and increasing.

This is only possible when

> 1.

Unwinding our rescaled variables, we see that an

> 1.

Unwinding our rescaled variables, we see that an

value

of unity puts the stagnation point halfway between the accretor

and the original value of Hoyle and Lyttleton.

This in turn implies a minimum accretion rate of 0.5 MHL.

value

of unity puts the stagnation point halfway between the accretor

and the original value of Hoyle and Lyttleton.

This in turn implies a minimum accretion rate of 0.5 MHL.

|

Figure 3. Curves where

d |

|

Figure 4. Curves where

d |

Again, I would like to remind the reader that the flow has been

assumed to remain isothermal with negligible gas pressure

throughout this discussion. This assumption is likely to be violated in

the wake, where densities will be high and radiative heat loss inefficient.

At the very least, thermal effects should be important close

to the stagnation point in the wake.

Horedt

(2000)

details an analysis similar to that

given above, but with a pressure term included.

The value of  (which

Horedt calls

x0) was found to lie between 0.6 and 3.5 for flows which

were supersonic at infinity and subject to Newtonian physics

(the polytropic and adiabatic indices were also free parameters

in this analysis).

(which

Horedt calls

x0) was found to lie between 0.6 and 3.5 for flows which

were supersonic at infinity and subject to Newtonian physics

(the polytropic and adiabatic indices were also free parameters

in this analysis).

Will the flow be stable?

Bondi and Hoyle asserted that

if  > 2 (note that

> 2 (note that

= 2 gives the solution of

Hoyle and Lyttleton), then the wake would become unstable to

perturbations which preserve axial symmetry. However, later analysis by

Cowie

(1977)

suggested that the wake should be unstable, regardless of the value

of

= 2 gives the solution of

Hoyle and Lyttleton), then the wake would become unstable to

perturbations which preserve axial symmetry. However, later analysis by

Cowie

(1977)

suggested that the wake should be unstable, regardless of the value

of  .

Subsequent numerical simulations and analytic work have shown

that Bondi-Hoyle-Lyttleton flow is far from stable, and

we will discuss the subject in section 4.2.

.

Subsequent numerical simulations and analytic work have shown

that Bondi-Hoyle-Lyttleton flow is far from stable, and

we will discuss the subject in section 4.2.

2.4. Connection to Bondi Accretion

Bondi (1952) studied spherically symmetric accretion onto a point mass. The analysis shows (see e.g. Frank et al. (2002)) that a Bondi radius may be defined as

|

(30) |

Flow outside this radius is subsonic, and the density is almost uniform. Within it, the gas becomes supersonic and moves towards a freefall solution. The similarities between equations 6 and 30 led Bondi to propose an interpolation formula:

|

(31) |

This is often known as the Bondi-Hoyle accretion rate. On the basis of their numerical calculations, Shima et al. (1985) suggest that equation 31 should acquire an extra factor of two, to become

|

(32) |

which then matches the original Hoyle-Lyttleton rate as the sound

speed becomes insignificant. The corresponding

BH

is formed by analogy with equation 7.

BH

is formed by analogy with equation 7.

Nomenclature in this field can be a little confused.

When papers refer to `Bondi-Hoyle accretion rates,' they may mean

equation 7, 31 or 32. In this review, I shall refer to pressure-free

flow as `Hoyle-Lyttleton' accretion and use MHL and

HL.

When there is gas pressure, I will talk about `Bondi-Hoyle accretion' and

use MBH and

HL.

When there is gas pressure, I will talk about `Bondi-Hoyle accretion' and

use MBH and

BH,

in the sense defined by equation 32. I shall use `Bondi-Hoyle-Lyttleton'

accretion to refer to the problem in general terms.

BH,

in the sense defined by equation 32. I shall use `Bondi-Hoyle-Lyttleton'

accretion to refer to the problem in general terms.