Observational study of normal galaxies at z

3 is still a

rather recent phenomenon. The last invited review on the subject to this

journal, only 5 years past

(Pritchet 1994),

began with the sad pronouncement that the predicted widespread

population of primeval galaxies had thus far escaped detection. At the

time, our knowledge of individual sources at z > 3 was

restricted to a dozen or so radio galaxies and a larger census of

quasars. Now the pioneering work of Steidel and collaborators has

uncovered several hundreds of Lyman-break systems at z

3 is still a

rather recent phenomenon. The last invited review on the subject to this

journal, only 5 years past

(Pritchet 1994),

began with the sad pronouncement that the predicted widespread

population of primeval galaxies had thus far escaped detection. At the

time, our knowledge of individual sources at z > 3 was

restricted to a dozen or so radio galaxies and a larger census of

quasars. Now the pioneering work of Steidel and collaborators has

uncovered several hundreds of Lyman-break systems at z

3 and

spectroscopically confirmed galaxies have recently crossed the z

= 5 barrier. Studies of the earliest epochs of the universe are no

longer restricted to AGN and quasar enthusiasts: since 1997 December

(Franx et al. 1997)

the most distant sources known to astronomers have consistently been

apparently normal, star-forming galaxies. Although this review

emphasizes the search techniques for identifying distant galaxies, we

now briefly consider what has been and can be learned about the early

universe from these studies.

3 and

spectroscopically confirmed galaxies have recently crossed the z

= 5 barrier. Studies of the earliest epochs of the universe are no

longer restricted to AGN and quasar enthusiasts: since 1997 December

(Franx et al. 1997)

the most distant sources known to astronomers have consistently been

apparently normal, star-forming galaxies. Although this review

emphasizes the search techniques for identifying distant galaxies, we

now briefly consider what has been and can be learned about the early

universe from these studies.

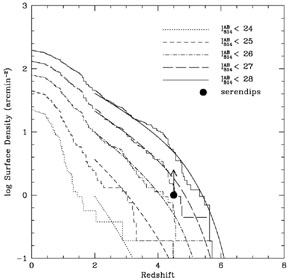

7.1. Surface Densities of High-Redshift Galaxies

Our various types of distant galaxies may be illustrative of peculiar, rare denizens of the cosmic past (the few powerful steep-spectrum radio sources at z > 4), or they may be more modest star-forming citizens, representative of an era when normal galaxies were modest fractions of L* and M*, typical luminosities and masses of the current cosmic epoch near z = 0.

In Table 5 we summarized the measured (estimated) surface densities of the various classes of distant sources discussed. Of particular note are the optical/near-infrared selected sources which present our best hope at being identified with precursors of present-day typical galaxies.

Fig. 10 illustrates the cumulative galaxy

surface density as a function of redshift and

I814AB magnitude - i.e., the surface

density of galaxies of redshift greater than a given redshift for

different magnitude thresholds. For example, to a limiting magnitude of

I814AB = 26,

5 galaxies

arcmin-2 are expected at z > 3. The histograms

derive from Stony Brook photometric redshift measurements in the

(Northern) HDF. The curves are fits to the measurements, assuming that

the evolving galaxy luminosity function is parameterized by the

Schechter (1976)

luminosity function,

5 galaxies

arcmin-2 are expected at z > 3. The histograms

derive from Stony Brook photometric redshift measurements in the

(Northern) HDF. The curves are fits to the measurements, assuming that

the evolving galaxy luminosity function is parameterized by the

Schechter (1976)

luminosity function,

|

(1) |

where  (L)

is the number density of galaxies per unit comoving volume and the

characteristic galaxy luminosity at rest-frame 1500 Å,

L*,1500, evolves with redshift as

(L)

is the number density of galaxies per unit comoving volume and the

characteristic galaxy luminosity at rest-frame 1500 Å,

L*,1500, evolves with redshift as

|

(2) |

Lanzetta (2000)

finds that the photometric redshifts are best fitted with a

characteristic absolute magnitude at 1500 Å

M*,1500z=3 = -19.5 ± 0.5, a

moderately steep luminosity function

= -1.43 ± 0.05,

and an evolving characteristic luminosity where

= -1.43 ± 0.05,

and an evolving characteristic luminosity where

= -0.7

± 0.4. Also plotted in Figure 10 is our

estimated lower limit to the surface density of serendipitous sources at

z > 4.5 from long-slit searches (> 1 arcmin-2).

= -0.7

± 0.4. Also plotted in Figure 10 is our

estimated lower limit to the surface density of serendipitous sources at

z > 4.5 from long-slit searches (> 1 arcmin-2).

|

Figure 10. Cumulative surface density of

galaxies as a function of redshift and limiting

I814AB magnitude. Histograms are Stony

Brook photometric redshift measurements of the cumulative surface

density of galaxies in the (Northern) HDF. Curves are fits to the

histograms assuming a parametrization of the evolving galaxy luminosity

function (see text). The point at z = 4.5 indicates our estimate

of the lower limit to the observed surface density of high-redshift

serendipitous

Ly |

Substantial caveats regarding this plot should be kept in mind before

extragalactic astronomers halt spectroscopic redshift surveys. First,

the modest angular size of the HDF implies that substantial cosmic

variance may skew the results, particularly at the brightest absolute

magnitudes for each redshift interval.

Gwyn (2000)

notes significant differences in the distribution of photometric

redshifts between the HDF-North and the HDF-South. Similarly, since the

HDF samples a very small volume of the local universe, the low-redshift

surface densities are poorly determined. Second, the redshifts are based

on photometric determinations rather than spectroscopic

determinations. As shown in

Section 4.2, photometric measurements are

fairly robust at the magnitude and redshift ranges tested thus

far. However, photometric redshifts are poorly tested in the difficult

spectroscopic redshift ranges of 1

z

z

2.5 and z

2.5 and z

4, as well as at

the extremely faint flux limits plotted in

Figure 10. Finally, these surface densities are

based on optically selected objects. If a large population of

dust-enshrouded galaxies exists, they may be missed in the optical

surveys.

4, as well as at

the extremely faint flux limits plotted in

Figure 10. Finally, these surface densities are

based on optically selected objects. If a large population of

dust-enshrouded galaxies exists, they may be missed in the optical

surveys.