Toomre and Toomre's suggestion that collisional disruption together with gas dissipation could feed all kinds of nuclear activity (see section 1.4), has inspired many searches for a connection between galaxy interactions and active galactic nuclei (AGN). As we will see these have turned up generally positive results, however, the correlations are not simple and direct, and many uncertainties and ambiguities remain. As in the case of the relation between SF and interactions, it seems that a number of processes are involved, each with its own parameter dependences and characteristic timescales. Given this fact, and the fact that there is a great deal of research underway, the results of which may change this situation enormously in coming years, we will not explore this subject very deeply here.

The sets of active nucleus galaxies and interacting galaxies are not identical, but probably have considerable overlap. Both sets have been targeted in attempts to map out the degree of overlap, and discover the mechanisms responsible. First we will consider searches for an excess of AGNs in interacting galaxies, and secondly attempts to determine whether there is an excess of interactions among galaxies with AGN. Each has its own difficulties (see the reviews of Heckman 1990, Stockton 1990, Laurikainen and Salo 1995, and Peterson 1997).

There are two fundamental difficulties in trying to survey AGNs in interacting galaxies. The first is that even in isolated galaxies, and more so in collisionally disturbed galaxies, the active nucleus can be buried beneath thick layers of gas and dust. This problem can be overcome at long wavelengths (radio to far-infrared), but in doing so we usually encounter the second problem. This is that high-resolution is needed to uniquely identify the AGN. The AGN and its associated accretion disk are very small, i.e., sub-parsec scales. However, they are often also very luminous, so the resolution problem could be bypassed given unique spectral signatures. Unfortunately, the most commonly used spectral characteristic are broad emission lines in the near-infrared to ultraviolet, which can be buried. Many of the more easily observed broadband or continuum diagnostics are not unique, but rather shared with the spectra of starburst regions (see below). Most of the early surveys were hobbled by these difficulties.

For example, radio (e.g., Hummel 1981, Condon et al. 1982), far-infrared (e.g., Soifer et al. 1984a), and near-infrared (e.g., Joseph et al. 1984, Lonsdale et al. 1984, and Cutri and McAlary 1985) surveys have found excess emission in the nuclei of interacting systems relative to normal systems (also see the numerous articles in Sulentic, Keel, and Telesco 1990). However, generally the resolution in these studies was not sufficient to determine the source of the emission. In some cases radio and radio-to-infrared spectral indices can be used to distinguish starbursts from "monsters" (Condon and Broderick 1988), but the nature of the monster isn't always clear.

Keel et al. (1985) and Kennicutt et al. (1987) found optical line emission enhanced in their interacting sample, with evidence that Seyfert activity in particular was somewhat enhanced. They also found some evidence that Seyfert nuclei were more frequent in very close pairs. This may be a consequence of close pairs being farther along in the merger process, and the fact that Seyferts are over-represented in merger remnants (e.g., Keel 1996).

Now let us turn to the question of how often AGN galaxies are involved in collisions? The primary difficulty with approaching the problem from this direction is that (luminous) AGN are not as common as they used to be when the universe was younger. This means that most AGNs are at great distances from us, and difficult to study. It was for this reason that the question of whether quasars generally are located in the centers of galaxies took a long time to answer. However, Hutchings (1995) notes that some 200 quasars had been resolved by 1995. These studies also provided insights into the relation between quasars and interactions. In the last few years high resolution HST studies of kinematics in the nuclei of nearby active galaxies have provided overwhelming evidence for the presence of supermassive black holes. There now seems to be little doubt that the AGN phenomenon is primarily as result of accretion onto these black holes (e.g., Maggorian, J. et al. 1998 and references therein).

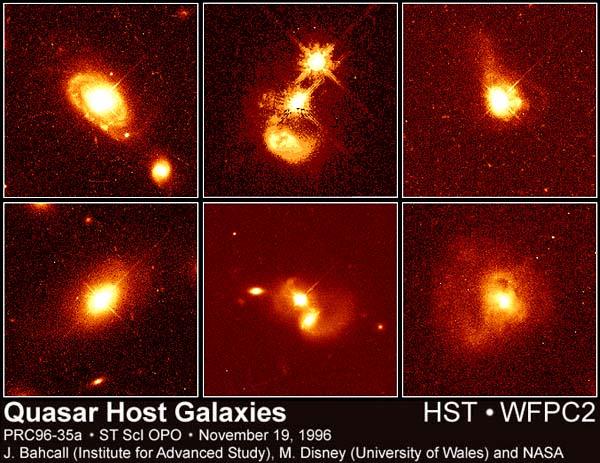

The early study of nearby Seyfert galaxies, which contain low luminosity AGNs, by Simkin, Su, and Schwartz (1980) found asymmetries or morphological disturbances in many of the host galaxies. They suggested that these asymmetries probably resulted either from internal causes, like bars, or from tidal interactions. Subsequent studies have confirmed that tidal distortions are common (e.g., MacKenty 1990 and the review of Heckman 1990). However, recent HST observations of quasar hosts have provided the strongest evidence to date of an association between interactions and AGN. The six objects with the HST planetary camera by Hutchings and Morris (1995, also Hutchings et al. 1994) all appeared to be in the "middle to late stages of merging with a smaller (M33 or LMC-size) companion." (The advantages and disadvantages of HST for such studies were also detailed in Hutchings 1995.) The three quasars in the sample of Boyce et al. (1996, also see Disney et al. 1995) also "appear embedded in spectacular interactions between two or more luminous galaxies." This latter sample consists of IRAS-bright (ULIRG) objects. The largest study published to date is that of Bahcall et al. (1997 and references therein), which contains 20 nearby, luminous quasars. Three of these objects appear to be in merging systems with extreme tidal distortions, and 13 have close companions (see Fig. 26). Since one of the merging systems does not have a close companion, at least 14 out of 20 systems may be involved in tidal interactions. Thus, it seems that quasar hosts involved in recent collisions are not only common, but perhaps ubiquitous.

|

Figure 26. Hubble Space Telescope image montage of QSO host galaxies, illustrating the frequency of disturbed or interacting hosts (from Bahcall et al. 1997, courtesy AURA/STSci.). |

This latter result on quasar companions is only the most recent example of a sequence of studies on AGN companion frequencies and environments that extends back more than two decades. Early studies generally found a higher than average incidence of companions around galaxies with AGN, though the results of various studies were not always in complete agreement. See the summaries of Heckman (1990) and Peterson (1997). Some recent studies have worked with very large samples of Seyferts. With a sample of 104 Seyferts Laurikainen and Salo (1995) concluded that while Seyferts have more companions than average, these are concentrated in a small number of systems, and so, Seyferts are not involved in interactions any more than other galaxies. Rafanelli, Violato, and Baruffolo (1995) found an interaction excess of a factor of a few in their complete, magnitude-limited sample, which contained 200 objects.

In these studies there are many difficulties associated with sample selection, companion identification and statistical analysis, whose consideration is beyond the scope of this paper. Presently, the only conclusion that does seem secure is that the possible triggering of Seyfert activity by interactions is not a direct, prompt, inevitable, and easily observable process!

One factor that makes understanding the AGN-interactions connection difficult is the likelihood that the connection is only one leg of a triangular relationship, in which starbursts are the third player. The previous chapter considered another leg of this triangle, the one connecting starbursts and interactions. The nature of the remaining leg, the connection between starbursts and AGN, is very unclear (despite a huge literature of studies of individual systems). At one extreme there is the possibility that the only connection is accidental or indirect, that both phenomena are triggered by similar conditions. Not far from this view is the proposal of Sanders et al. (1988) that the "tremendous reservoir of molecular gas" funneled into the centers of ULIRG merger remnants induces the formation of both massive starbursts and AGN ("buried quasars"). Both forms of activity drive out the gas and dust, the starburst dies down and the quasar is revealed. One clear prediction of this model is that quasars have a significantly longer lifetime than super-starbursts. A variation of this model, in which a supermassive black hole at the heart of the AGN is fueled by the "super" mass loss resulting from the super-starburst, was studied by Norman and Scoville (1988). In this model starburst and AGN can be successive, so that the AGN lifetime need not be as long.

At the other extreme we have the idea promoted by Terlevich and collaborators that the black hole engine is not necessary, but rather (radio quiet) AGN might consist only of buried or unresolved starbursts and supernova remnants (e.g., Terlevich 1994). AGN variability is accounted for by frequent supernova explosions and interactions of supernova remnants with the dense, turbulent environment.

Heckman (1990) has pointed out the difficulty in determining which of these two extreme theories is correct. He begins his review article by pointing out that the energy output of AGN and super-starbursts are comparable, and mischieviously concludes with the observation that

... it is amusing (though possibly irrelevant) that the spectra of BAL quasars bear a superficial resemblence to the spectra of massive stars undergoing mass-loss! (Heckman 1990).

Nonetheless, in a later review, Heckman (1994) argues strongly against the Terlevich model, in part on the basis that the supernova energy requirements are not consistent with other properties of starbursts. Terlevich (1994) disagrees with Heckman's figures. As in the previous chapter the nature of the IMF is crucial. New VLBI (very long baseline interferometry) results may resolve the problem. For example, in a study of 18 ULIRGs Smith, Lonsdale and Lonsdale (1998) found that the compact radio cores in 7 out of the 11 that they modeled could be accounted for by starbursts and radio supernovae. The remaining 4 objects could not be fit with starburst models, and "almost certainly house" accreting black hole AGNs. Genzel et al.'s (1998) ISO (Infrared Space Observatory) mid-infrared spectroscopic study of a comparable sample reached similar conclusions about the relative roles of starbursts and AGN.

In conclusion, understanding the nature of the three-way relationship between interactions, starbursts and AGN has proven extremely difficult. Indeed, the Terlevich-Heckman dialogue shows the difficulty in determining whether we're looking at the results of accretion onto a supermassive black hole, or a pure starburst. However, VLBI observations are beginning to answer these questions. Self-consistent interaction simulations have taught us that the merger process usually involves multiple collisions of two or more galaxies, and that SF is probably induced by a variety of dynamical processes, whose characteristic timescales span orders of magnitude. Thus, we cannot expect that connection and the connections to interactions to be very obvious in most current statistical studies.

On the other hand, Gunn's (1979) suggestion that the key aspect of this problem is how to get the gas fuel down to the very small scales of the accretion disk. If we accept this then it follows that theoretical and numerical studies of specific fueling processes are worthwhile, as are attempts to identify observational examples. There has, in fact, been a great deal of work along these lines, some of which we will consider in the next section.

In their 1992 review Barnes and Hernquist pessimistically conclude - "theoretical studies on the relevance of mergers to quasar activity mainly comprise wishful thinking."(!) They cite two particular difficulties: 1) Gunn's feeding scale problem, 2) the possibility that the quasar hosts had little to do with the processes being modeled in merger simulations. In the years since their review the intense research in this area has provided more grounds for optimism. The second problem is substantially alleviated by the HST observations described above, which provide direct evidence that some, and the implication that most, of the quasar hosts are collisional systems. The feeding scale problem remains tricky, however.

Simulations of large-scale processes like mergers and collisionally induced bar formation have improved with ever more particles and better resolution. This gives us more confidence in their basic results, and allows more detailed studies of funneling mechanisms (see Hernquist and Barnes, 1994, and other reviews in Shlosman 1994). The feeding scale problem begins to seem rather academic when these models show that 2/3 of the gas is funneled down to a scale of a few hundred parsecs in a major merger. While it is true that there are a couple of magnitudes left to get down to accretion disk sizes, this is still a very large mass of gas in a quite small volume! On the other hand, even if we accept this case as proven, we are still left with a number of hard questions. E.g., does it take a major merger to fuel a quasar? What about the other types of AGN, do they also require a major merger to initiate and sustain their activity?

While there are no definite answers to these questions at present, other candidate fueling mechanisms are being investigated. Among the oldest idea is that dissipation and the non-axisymmetric forces in the disks of barred galaxies can lead to gas funneling without the additional help of collisions or mergers. (Many barred galaxies are not presently interacting.) Unfortunately for this idea, observational studies to search for a correlation between the presence of a large-scale bar and an AGN have yielded conflicting results (see the references in Peterson 1997). Most studies probably have not been sensitive enough to discover weak, small-scale bars. For example, the very recent near-infrared Seyfert imaging survey of Mulchaey and Regan (1997) found bars in 55% of the galaxies classified as non-barred in the optical. However, they found the same percentage of bars in both the Seyfert and the control sample. In addition, 30% of their Seyfert sample showed no evidence for bars.

The question of fueling by bars was also investigated by Ho, Filippenko and Sargent (1997) using data from their optical spectroscopic survey of (> 300) galaxies. They found no significant evidence of increased central SF or incidence of nuclear activity in the late-type (Sc-Sm) galaxies with bars versus those without. However, they did find a measureable increase in the SF of the early-type, barred galaxies of their sample. They conjecture that the reason for this is that inner Lindblad resonances are more common in the early-types, which have larger bulges. While the SF may be enhanced by gas accumulation in a ring at the radius of the resonance, it is prevented from fueling nuclear activity in the center.

Moreover, barred galaxies may suffer from a more severe feeding scale problem than do merger remnants. That is, most bars may not be able to funnel enough gas down deep enough to feed the accretion disk without the help of an additional process. Several candidate for this process have been considered recently. For example, Noguchi (1994) and Shlosman and Heller (1994) emphasize the role of what might be called "bootstrapping" via the self-gravity in the inflowing gas. Heller and Shlosman (1994a, b) have also presented models showing much enhanced gas inflow driven by enhanced viscosity and angular momentum transport resulting from a starburst triggered by the initial bar-induced inflow. Finally, there is also the bars within bars mechanism discussed in section 5.6. Mulchaey and Regan (1997) looked explicitly for evidence of this process. They did not find many candidate multiple bar systems, and most of the ones they did were in the non-Seyfert control sample. However, it is also believed that as the central black hole grows it can generate substantial dynamical heating, inhibiting or destroying (multiple) bars (e.g., Friedli 1994, Shlosman and Heller 1994a).

At this point the reader will recall that we began considering dynamical mechanisms in hopes of finding a little more enlightment than was offered by the observational surveys. Instead, we seem to have found a great deal of dynamical complexity. Worse yet, we have not yet exhausted the list of dynamical processes; there are at least several important variations on the themes above. One is the process of mass transfer in non-merging collisions described in section 4.1. When the transferred gas has low angular momentum along the host galaxy spin axis it will mix with ambient gas and accumulate in the central regions as in mergers. Most of these interactions are less extreme than mergers, except for small companions involved in direct collisions. Therefore, we would expect less direct feeding of the AGN, but indirect feeding via bar instabilities, induced starbursts, etc., seems more likely.

Yet another possibility is that the active nucleus might contain more than one supermassive black hole. If most galaxies harbor a supermassive black hole, than massive binary or multiple black holes seem likely in the nucleus of a merger remnant (Begelman, Blanford and Rees 1980). Makino (1997) has recently presented self-consistent N-body simulations of this process. A supermassive binary black hole orbit decays as a result of scattering stars (two-body "thermal" relaxation), resonant scattering, dynamical friction (collective scattering), and gravitational radiation if the orbit is small or highly eccentric. While the mean value of the average decay timescale is still being debated, it is generally thought to be longer than galaxy collision timescales. The (long-term) existence of such a binary would considerably ease the feeding scale problem. The accretion disks around the orbiting black holes will interact with gas in a much larger volume in the central disk than a single black hole, and will generate a non-axisymmetric gravitational disturbance much like a small-scale bar, funneling gas inward.

By now it is clear that there are a variety of possible solutions to Gunn's feeding scale problem. The triangle of processes described above, with vertices labeled AGN, starburst and interactions, should be enlarged to a pentagon with the addition of vertices for bars and binary black holes, at least. On a more optimistic note, the high resolution observations of the near neighborhood of AGNs and their accretion disks or torii that are becoming available provide a much better understanding of the phenomena. This may be a prerequisite to a better understanding of the connections to large-scale phenomena.

A final item on our wish list is more detailed and complete surveys. Keel's (1996) recent imaging and spectroscopic study of Seyfert galaxies with companions, noted above, provides an good example of what we can hope to find. Even negative results, like Keel's finding that the presence of an AGN doesn't seem to correlate with the type of collisional interaction, are helpful. In fact, this result is a surprise, since possible fueling mechanisms like mass transfer and induced bar formation do depend strongly on the nature of the interaction. Are the time delays associated with fueling long enough to make it impossible to associate the effect with the initial cause, are these particular fueling processes simply not that important, or are many processes equally important? Keel's result that there does seem to a (complicated) dependence on the magnitude of the kinematic disturbance points the way to future studies.