Copyright © 2002 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

| Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2002. 40:

171-216 Copyright © 2002 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved |

When the temperature of the Universe was ~ 3000K at a redshift

z*  103, electrons and

protons combined to form neutral hydrogen, an event usually known

as recombination

([Peebles, 1968,

Zel'dovich et al, 1969];

see [Seager et al, 2000] for

recent refinements).

Before this epoch, free electrons acted as glue between the photons

and the baryons through Thomson and Coulomb scattering,

so the cosmological plasma

was a tightly coupled photon-baryon fluid

[Peebles & Yu, 1970].

The spectrum depicted in Plate 1 can be

explained almost completely

by analyzing the behavior of this pre-recombination fluid.

103, electrons and

protons combined to form neutral hydrogen, an event usually known

as recombination

([Peebles, 1968,

Zel'dovich et al, 1969];

see [Seager et al, 2000] for

recent refinements).

Before this epoch, free electrons acted as glue between the photons

and the baryons through Thomson and Coulomb scattering,

so the cosmological plasma

was a tightly coupled photon-baryon fluid

[Peebles & Yu, 1970].

The spectrum depicted in Plate 1 can be

explained almost completely

by analyzing the behavior of this pre-recombination fluid.

In Section 3.1, we start from the two basic equations of fluid mechanics and derive the salient characteristics of the anisotropy spectrum: the existence of peaks and troughs; the spacing between adjacent peaks; and the location of the first peak. These properties depend in decreasing order of importance on the initial conditions, the energy contents of the Universe before recombination and those after recombination. Ironically, the observational milestones have been reached in almost the opposite order. Throughout the 1990's constraints on the location of the first peak steadily improved culminating with precise determinations from the TOCO [Miller et al, 1999], Boomerang, [de Bernardis et al, 2000] and Maxima-1 [Hanany et al, 2000] experiments (see Plate 1 top). In the working cosmological model it shows up right where it should be if the present energy density of the Universe is equal to the critical density, i.e. if the Universe is flat. The skeptic should note that the working cosmological model assumes a particular form for the initial conditions and energy contents of the Universe before recombination which we shall see have only recently been tested directly (with an as yet much lower level of statistical confidence) with the higher peaks.

In Section 3.2 we introduce the initial conditions that apparently are the source of all clumpiness in the Universe. In the context of ab initio models, the term "initial conditions" refers to the physical mechanism that generates the primordial small perturbations. In the working cosmological model, this mechanism is inflation and it sets the initial phase of the oscillations to be the same across all Fourier modes. Remarkably, from this one fact alone comes the prediction that there will be peaks and troughs in the amplitude of the oscillations as a function of wavenumber. Additionally the inflationary prediction of an approximately scale-invariant amplitude of the initial perturbations implies roughly scale-invariant oscillations in the power spectrum. And inflation generically predicts a flat Universe. These are all falsifiable predictions of the simplest inflationary models and they have withstood the test against observations to date.

The energy contents of the Universe before recombination all leave their distinct signatures on the oscillations as discussed in Section 3.3-Section 3.5. In particular, the cold dark matter and baryon signatures have now been seen in the data [Halverson et al, 2001, Netterfield et al, 2001, Lee et al, 2001]. The coupling between electrons and photons is not perfect, especially as one approaches the epoch of recombination. As discussed in Section 3.6, this imperfect coupling leads to damping in the anisotropy spectrum: very small scale inhomogeneities are smoothed out. The damping phenomenon has now been observed by the CBI experiment [Padin et al, 2001]. Importantly, fluid imperfections also generate linear polarization as covered in Section 3.7. Because the imperfection is minimal and appears only at small scales, the polarization generated is small and has not been detected to date.

After recombination the photons basically travel freely to us today, so the problem of translating the acoustic inhomogeneities in the photon distribution at recombination to the anisotropy spectrum today is simply one of projection. This projection depends almost completely on one number, the angular diameter distance between us and the surface of last scattering. That number depends on the energy contents of the Universe after recombination through the expansion rate. The hand waving projection argument of Section 3.1 is formalized in Section 3.8, in the process introducing the popular code used to compute anisotropies, CMBFAST. Finally, we discuss the sensitivity of the acoustic peaks to cosmological parameters in Section 3.9.

For pedagogical purposes, let us begin with an idealization of a perfect photon-baryon fluid and neglect the dynamical effects of gravity and the baryons. Perturbations in this perfect fluid can be described by a simple continuity and an Euler equation that encapsulate the basic properties of acoustic oscillations.

The discussion of acoustic oscillations will take place exclusively in Fourier space. For example, we decompose the monopole of the temperature field into

|

(6) |

and omit the subscript 00 on the Fourier amplitude.

Since perturbations

are very small, the evolution equations are linear, and different Fourier

modes evolve independently. Therefore, instead of partial differential

equations for a field

(x), we have

ordinary differential equations for

(x), we have

ordinary differential equations for

(k). In fact,

due to rotational symmetry, all

(k). In fact,

due to rotational symmetry, all

(k) for a

given k obey the same equations. Here and in the following sections,

we omit the wavenumber argument k where no

confusion with physical space quantities will arise.

(k) for a

given k obey the same equations. Here and in the following sections,

we omit the wavenumber argument k where no

confusion with physical space quantities will arise.

Temperature perturbations in Fourier space obey

|

(7) |

This equation for the photon temperature

, which does indeed

look like the familiar continuity equation

in Fourier space (derivatives

, which does indeed

look like the familiar continuity equation

in Fourier space (derivatives

become wavenumbers

k), has

a number of subtleties hidden in it, due to the cosmological setting.

First, the "time" derivative here is actually with respect to

conformal time

become wavenumbers

k), has

a number of subtleties hidden in it, due to the cosmological setting.

First, the "time" derivative here is actually with respect to

conformal time

dt

/ a(t).

Since we are working in units in which the speed of light c = 1,

dt

/ a(t).

Since we are working in units in which the speed of light c = 1,

is also the

maximum comoving distance a particle could have traveled

since t = 0. It is often called

the comoving horizon or more specifically the comoving

particle horizon. The physical horizon is a times the

comoving horizon.

is also the

maximum comoving distance a particle could have traveled

since t = 0. It is often called

the comoving horizon or more specifically the comoving

particle horizon. The physical horizon is a times the

comoving horizon.

Second, the photon fluid velocity here

v has been written as a scalar instead of a vector.

In the early universe, only the velocity component parallel to the

wavevector k is

expected to be important, since they alone have a source in gravity.

Specifically,

v

has been written as a scalar instead of a vector.

In the early universe, only the velocity component parallel to the

wavevector k is

expected to be important, since they alone have a source in gravity.

Specifically,

v = - iv

= - iv

.

In terms of the moments introduced in Section 2,

v

.

In terms of the moments introduced in Section 2,

v represents a dipole moment directed along k.

The factor of 1/3 comes about since continuity conserves photon number

not temperature and the number density

n

represents a dipole moment directed along k.

The factor of 1/3 comes about since continuity conserves photon number

not temperature and the number density

n

T3.

Finally, we emphasize that, for the time being, we are neglecting the

effects of gravity.

T3.

Finally, we emphasize that, for the time being, we are neglecting the

effects of gravity.

The Euler equation for a fluid is an expression of momentum conservation.

The momentum density of the photons is

(

+

p

+

p )

v

)

v , where the photon pressure

p

, where the photon pressure

p =

=

/ 3.

In the absence of gravity and viscous fluid imperfections, pressure

gradients

/ 3.

In the absence of gravity and viscous fluid imperfections, pressure

gradients  p

p =

=

/ 3

supply the only force. Since

/ 3

supply the only force. Since

T4,

this becomes

4k

T4,

this becomes

4k

/ 3 in Fourier space. The Euler equation then becomes

/ 3 in Fourier space. The Euler equation then becomes

|

(8) |

Differentiating the continuity equation and inserting the Euler equation yields the most basic form of the oscillator equation

|

(9) |

where cs  (

( /

/

)1/2 = 1 / 31/2 is the sound speed

in the (dynamically baryon-free) fluid.

What this equation says is that pressure gradients act as a

restoring force to any initial perturbation in the system which thereafter

oscillate at the speed of sound. Physically these temperature

oscillations represent the heating and cooling of a fluid that

is compressed and rarefied by a standing sound or acoustic wave.

This behavior continues until recombination. Assuming negligible

initial velocity perturbations, we have a temperature distribution at

recombination of

)1/2 = 1 / 31/2 is the sound speed

in the (dynamically baryon-free) fluid.

What this equation says is that pressure gradients act as a

restoring force to any initial perturbation in the system which thereafter

oscillate at the speed of sound. Physically these temperature

oscillations represent the heating and cooling of a fluid that

is compressed and rarefied by a standing sound or acoustic wave.

This behavior continues until recombination. Assuming negligible

initial velocity perturbations, we have a temperature distribution at

recombination of

|

(10) |

where

s =  cs

d

cs

d

/

31/2 is the distance sound can

travel by

/

31/2 is the distance sound can

travel by  ,

usually called the sound horizon. Asterisks denote

evaluation at recombination z*.

,

usually called the sound horizon. Asterisks denote

evaluation at recombination z*.

In the limit of scales large compared with the sound horizon ks

<< 1,

the perturbation is frozen into its initial conditions. This is the gist of

the statement that the large-scale anisotropies measured by COBE directly

measure the initial conditions. On small scales, the amplitude of the

Fourier modes will exhibit temporal oscillations, as shown in

Figure 1

[with  = 0,

= 0,

i =

3

i =

3 (0) for this

idealization].

Modes that are caught at maxima or minima of their oscillation at

recombination correspond to peaks in the

power, i.e. the variance of

(0) for this

idealization].

Modes that are caught at maxima or minima of their oscillation at

recombination correspond to peaks in the

power, i.e. the variance of

(k,

(k,

*). Because

sound takes half as long to travel half as far, modes corresponding

to peaks follow a harmonic relationship

kn = n

*). Because

sound takes half as long to travel half as far, modes corresponding

to peaks follow a harmonic relationship

kn = n

/

s*, where n is an integer (see

Figure 1a).

/

s*, where n is an integer (see

Figure 1a).

How does this spectrum of inhomogeneities at recombination

appear to us today? Roughly speaking, a spatial inhomogeneity

in the CMB temperature of wavelength

appears as an angular

anisotropy of scale

appears as an angular

anisotropy of scale

/ D where

D(z) is the

comoving angular diameter distance from the observer to redshift

z. We will address this issue more formally in

Section 3.8. In a flat universe,

D* =

/ D where

D(z) is the

comoving angular diameter distance from the observer to redshift

z. We will address this issue more formally in

Section 3.8. In a flat universe,

D* =

0 -

0 -

*

*

0, where

0, where

0

0

(z = 0).

In harmonic space, the relationship implies a coherent series of

acoustic peaks in the anisotropy spectrum, located at

(z = 0).

In harmonic space, the relationship implies a coherent series of

acoustic peaks in the anisotropy spectrum, located at

|

(11) |

To get a feel for where these features should appear, note that in a

flat matter dominated universe

(1 +

z)-1/2 so that

(1 +

z)-1/2 so that  * /

* /

0

0

1/30

1/30

2°. Equivalently

2°. Equivalently

1

1

200. Notice that

since we are measuring ratios of distances

the absolute distance scale drops out; we shall see in

Section 3.5

that the Hubble constant sneaks back into the problem because the Universe

is not fully matter-dominated at recombination.

200. Notice that

since we are measuring ratios of distances

the absolute distance scale drops out; we shall see in

Section 3.5

that the Hubble constant sneaks back into the problem because the Universe

is not fully matter-dominated at recombination.

In a spatially curved universe, the angular diameter distance

no longer equals the coordinate distance making the peak locations

sensitive to the spatial curvature of the Universe

[Doroshkevich et al, 1978,

Kamionkowski et al, 1994].

Consider first a closed universe with radius of curvature

R = H0-1

| tot -

1|-1/2. Suppressing one spatial coordinate yields

a 2-sphere geometry with the observer situated at the

pole (see Figure 2). Light travels on

lines of longitude.

A physical scale

tot -

1|-1/2. Suppressing one spatial coordinate yields

a 2-sphere geometry with the observer situated at the

pole (see Figure 2). Light travels on

lines of longitude.

A physical scale  at

fixed latitude given by

the polar angle

at

fixed latitude given by

the polar angle  subtends an angle

subtends an angle  =

=

/ R

sin

/ R

sin  .

For

.

For  << 1,

a Euclidean analysis would infer a distance

D = R sin

<< 1,

a Euclidean analysis would infer a distance

D = R sin  ,

even though the coordinate distance along the arc is

d =

,

even though the coordinate distance along the arc is

d =  R; thus

R; thus

|

(12) |

For open universes, simply replace sin with sinh.

The result is that objects in an open (closed) universe are closer

(further) than they appear, as if seen through a lens.

In fact one way of viewing this effect is as the gravitational

lensing due to the background density (c.f.

Section 4.2.4).

A given comoving scale at a fixed distance subtends

a larger (smaller) angle in a closed (open) universe than a flat universe.

This strong scaling with spatial curvature indicates that

the observed first peak at

1

1

200 constrains

the geometry to be nearly spatially flat. We will implicitly

assume spatial flatness in the following sections unless otherwise

stated.

200 constrains

the geometry to be nearly spatially flat. We will implicitly

assume spatial flatness in the following sections unless otherwise

stated.

Finally in a flat dark energy dominated universe, the conformal age of

the Universe decreases approximately as

0

0

0(1

+ ln

0(1

+ ln m0.085). For reasonable

m0.085). For reasonable

m, this

causes only a small shift

of

m, this

causes only a small shift

of  1 to lower

multipoles (see Plate 4) relative

to the effect of curvature. Combined with the effect of

the radiation near recombination, the peak locations provides a means to

measure the physical age t0 of a flat universe

[Hu et al, 2001].

1 to lower

multipoles (see Plate 4) relative

to the effect of curvature. Combined with the effect of

the radiation near recombination, the peak locations provides a means to

measure the physical age t0 of a flat universe

[Hu et al, 2001].

As suggested above, observations of the location of the first peak strongly

point to a flat universe. This is encouraging news for adherents of

inflation, a theory which initially predicted

tot = 1

at a time when few astronomers would sign on to such a high value (see

[Liddle & Lyth, 1993]

for a review).

However, the argument

for inflation goes beyond the confirmation of flatness. In particular,

the discussion of the last subsection begs the question: whence

tot = 1

at a time when few astronomers would sign on to such a high value (see

[Liddle & Lyth, 1993]

for a review).

However, the argument

for inflation goes beyond the confirmation of flatness. In particular,

the discussion of the last subsection begs the question: whence

(0),

the initial conditions of the temperature fluctuations? The answer requires

the inclusion of gravity and considerations of causality which point

to inflation as the origin of structure in the Universe.

(0),

the initial conditions of the temperature fluctuations? The answer requires

the inclusion of gravity and considerations of causality which point

to inflation as the origin of structure in the Universe.

The calculations of the typical angular scale of the acoustic oscillations in the last section are familiar in another context: the horizon problem. Because the sound speed is near the speed of light, the degree scale also marks the extent of a causally connected region or particle horizon at recombination. For the picture in the last section to hold, the perturbations must have been laid down while the scales in question were still far outside the particle horizon 2. The recent observational verification of this basic peak structure presents a problem potentially more serious than the original horizon problem of approximate isotropy: the mechanism which smooths fluctuations in the Universe must also regenerate them with superhorizon sized correlations at the 10-5 level. Inflation is an idea that solves both problems simultaneously.

The inflationary paradigm postulates that an early phase of near exponential expansion of the Universe was driven by a form of energy with negative pressure. In most models, this energy is usually provided by the potential energy of a scalar field. The inflationary era brings the observable universe to a nearly smooth and spatially flat state. Nonetheless, quantum fluctuations in the scalar field are unavoidable and also carried to large physical scales by the expansion. Because an exponential expansion is self-similar in time, the fluctuations are scale-invariant, i.e. in each logarithmic interval in scale the contribution to the variance of the fluctuations is equal. Since the scalar field carries the energy density of the Universe during inflation, its fluctuations induce variations in the spatial curvature [Guth & Pi, 1985, Hawking, 1982, Bardeen et al, 1983]. Instead of perfect flatness, inflation predicts that each scale will resemble a very slightly open or closed universe. This fluctuation in the geometry of the Universe is essentially frozen in while the perturbation is outside the horizon [Bardeen, 1980].

Formally, curvature fluctuations are perturbations to the space-space

piece of the metric. In a Newtonian coordinate system, or gauge, where

the metric is diagonal, the spatial curvature fluctuation is called

gij =

2a2

gij =

2a2

ij (see e.g.

[Ma & Bertschinger, 1995]).

The more familiar Newtonian potential is the time-time fluctuation

ij (see e.g.

[Ma & Bertschinger, 1995]).

The more familiar Newtonian potential is the time-time fluctuation

gtt =

2

gtt =

2 and is

approximately

and is

approximately

-

-

. Approximate scale

invariance then says that

. Approximate scale

invariance then says that

2

2

k3

P

k3

P (k) /

2

(k) /

2 2

2

kn-1

where P

kn-1

where P (k) is the

power spectrum of

(k) is the

power spectrum of  and

the tilt n

and

the tilt n  1.

1.

Now let us relate the inflationary prediction of scale-invariant

curvature fluctuations to the initial temperature fluctuations.

Newtonian intuition based on the Poisson equation

k2  =

4

=

4 Ga2

Ga2

tells us that on

large scales (small k) density and hence temperature

fluctuations should be negligible compared with Newtonian potential.

General relativity says otherwise because the Newtonian potential is also

a time-time fluctuation in the metric. It corresponds to a temporal shift of

tells us that on

large scales (small k) density and hence temperature

fluctuations should be negligible compared with Newtonian potential.

General relativity says otherwise because the Newtonian potential is also

a time-time fluctuation in the metric. It corresponds to a temporal shift of

t / t =

t / t =

. The CMB temperature

varies as the inverse of the

scale factor, which in turn depends on time as

a

. The CMB temperature

varies as the inverse of the

scale factor, which in turn depends on time as

a  t2/[3(1+p/

t2/[3(1+p/ )]. Therefore, the fractional change in the

CMB temperature

)]. Therefore, the fractional change in the

CMB temperature

|

(13) |

Thus, a temporal shift produces a temperature perturbation of

-  / 2 in the radiation

dominated era (when p =

/ 2 in the radiation

dominated era (when p =

/ 3) and

-2

/ 3) and

-2 / 3 in the matter

dominated epoch (p = 0)

([Peacock, 1991];

[White & Hu, 1997]).

The initial temperature perturbation is

therefore inextricably linked with the initial gravitational potential

perturbation. Inflation predicts scale-invariant initial

fluctuations in both the CMB temperature and the spatial curvature

in the Newtonian gauge.

/ 3 in the matter

dominated epoch (p = 0)

([Peacock, 1991];

[White & Hu, 1997]).

The initial temperature perturbation is

therefore inextricably linked with the initial gravitational potential

perturbation. Inflation predicts scale-invariant initial

fluctuations in both the CMB temperature and the spatial curvature

in the Newtonian gauge.

Alternate models which seek to obey the causality can generate curvature

fluctuations only inside the particle horizon. Because the perturbations

are then not generated at the same epoch independent of scale, there is

no longer a unique

relationship between the phase of the oscillators. That is, the argument

of the cosine in Equation (10) becomes ks* +

(k),

where

(k),

where  is a phase

which can in principle be different for different wavevectors,

even those with the same magnitude k. This can lead to

temporal incoherence in the oscillations and

hence a washing out of the acoustic peaks

[Albrecht et al, 1996],

most notably in cosmological defect models

[Allen et al, 1997,

Seljak et al, 1997].

Complete incoherence is not a strict requirement of causality since there

are other ways to synch up the oscillations. For example, many

isocurvature models, where the initial spatial curvature is unperturbed,

are coherent since their oscillations

begin with the generation of curvature fluctuations at horizon

crossing

[Hu & White, 1996].

Still they typically have

is a phase

which can in principle be different for different wavevectors,

even those with the same magnitude k. This can lead to

temporal incoherence in the oscillations and

hence a washing out of the acoustic peaks

[Albrecht et al, 1996],

most notably in cosmological defect models

[Allen et al, 1997,

Seljak et al, 1997].

Complete incoherence is not a strict requirement of causality since there

are other ways to synch up the oscillations. For example, many

isocurvature models, where the initial spatial curvature is unperturbed,

are coherent since their oscillations

begin with the generation of curvature fluctuations at horizon

crossing

[Hu & White, 1996].

Still they typically have

0 (c.f.

[Turok, 1996]).

Independent of the angular diameter distance

D*, the ratio of the peak locations gives the

phase:

0 (c.f.

[Turok, 1996]).

Independent of the angular diameter distance

D*, the ratio of the peak locations gives the

phase:  1 :

1 :

2 :

2 :

3 ~ 1 : 2 :

3 for

3 ~ 1 : 2 :

3 for  = 0.

Likewise independent of a constant phase, the spacing of the peaks

= 0.

Likewise independent of a constant phase, the spacing of the peaks

n -

n -

n-1 =

n-1 =

A gives a measure

of the angular diameter distance

[Hu & White, 1996].

The observations, which indicate coherent oscillations with

A gives a measure

of the angular diameter distance

[Hu & White, 1996].

The observations, which indicate coherent oscillations with

= 0,

therefore have provided a non-trivial test of

the inflationary paradigm and supplied

a substantially more stringent version of the horizon problem

for contenders to solve.

= 0,

therefore have provided a non-trivial test of

the inflationary paradigm and supplied

a substantially more stringent version of the horizon problem

for contenders to solve.

We saw above that fluctuations in a scalar field during inflation

get turned into temperature fluctuations via the intermediary of gravity.

Gravity affects  in

more ways than this. The Newtonian potential and spatial curvature alter

the acoustic oscillations by providing a gravitational force on

the oscillator. The Euler equation (8)

gains a term on the rhs due to the gradient of

the potential k

in

more ways than this. The Newtonian potential and spatial curvature alter

the acoustic oscillations by providing a gravitational force on

the oscillator. The Euler equation (8)

gains a term on the rhs due to the gradient of

the potential k .

The main effect of gravity then is

to make the oscillations a competition between pressure

gradients k

.

The main effect of gravity then is

to make the oscillations a competition between pressure

gradients k and potential gradients

k

and potential gradients

k with

an equilibrium when

with

an equilibrium when  +

+

= 0.

= 0.

Gravity also changes the continuity equation. Since the Newtonian

curvature is essentially a perturbation to the scale factor, changes

in its value also generate temperature perturbations by analogy to

the cosmological redshift

= -

= -

and so

the continuity equation (7) gains a contribution of -

and so

the continuity equation (7) gains a contribution of -

on

the rhs.

on

the rhs.

These two effects bring the oscillator equation (9) to

|

(14) |

In a flat universe and in the absence

of pressure,  and

and

are constant. Also, in

the absence of baryons,

cs2 = 1/3 so the new oscillator equation

is identical to Equation (9) with

are constant. Also, in

the absence of baryons,

cs2 = 1/3 so the new oscillator equation

is identical to Equation (9) with

replaced by

replaced by

+

+

. The solution

in the matter dominated epoch is then

. The solution

in the matter dominated epoch is then

|

(15) |

where

md

represents the start of the matter dominated epoch

(see Figure 1a).

We have used the matter dominated "initial conditions" for

md

represents the start of the matter dominated epoch

(see Figure 1a).

We have used the matter dominated "initial conditions" for

given in the previous section assuming large scales,

ksmd << 1.

given in the previous section assuming large scales,

ksmd << 1.

The results from the idealization of

Section 3.1 carry through with a few exceptions. Even

without an initial temperature fluctuation to displace the oscillator,

acoustic oscillations would arise by the infall and compression

of the fluid into gravitational

potential wells. Since it is the effective temperature

+

+

that oscillates, they

occur even if

that oscillates, they

occur even if

(0) = 0. The quantity

(0) = 0. The quantity

+

+

can be thought of as an

effective temperature in another way: after recombination, photons

must climb out of the potential well to the observer and thus suffer

a gravitational redshift of

can be thought of as an

effective temperature in another way: after recombination, photons

must climb out of the potential well to the observer and thus suffer

a gravitational redshift of

T / T

=

T / T

=  . The effective

temperature fluctuation is therefore also the observed temperature

fluctuation. We now see that the large scale limit of

Equation (15) recovers the famous Sachs-Wolfe result

that the observed temperature perturbation is

. The effective

temperature fluctuation is therefore also the observed temperature

fluctuation. We now see that the large scale limit of

Equation (15) recovers the famous Sachs-Wolfe result

that the observed temperature perturbation is

/ 3

and overdense regions correspond to cold spots on the sky

[Sachs & Wolfe, 1967].

When

/ 3

and overdense regions correspond to cold spots on the sky

[Sachs & Wolfe, 1967].

When  < 0, although

< 0, although

is positive, the

effective temperature

is positive, the

effective temperature

+

+

is negative.

The plasma begins effectively rarefied in gravitational potential wells.

As gravity compresses the fluid and pressure resists, rarefaction becomes

compression and rarefaction again. The first peak corresponds to the

mode that is caught in its first compression

by recombination. The second peak at roughly half the wavelength corresponds

to the mode that went through a full cycle of compression and rarefaction

by recombination. We will use this language of the compression

and rarefaction phase inside initially overdense regions but one should bear

in mind that there are an equal number of initially underdense regions

with the opposite phase.

is negative.

The plasma begins effectively rarefied in gravitational potential wells.

As gravity compresses the fluid and pressure resists, rarefaction becomes

compression and rarefaction again. The first peak corresponds to the

mode that is caught in its first compression

by recombination. The second peak at roughly half the wavelength corresponds

to the mode that went through a full cycle of compression and rarefaction

by recombination. We will use this language of the compression

and rarefaction phase inside initially overdense regions but one should bear

in mind that there are an equal number of initially underdense regions

with the opposite phase.

So far we have been neglecting the baryons in the dynamics of

the acoustic oscillations. To see whether this is a reasonable

approximation consider the photon-baryon momentum density

ratio R = (pb +

b

/ (p

b

/ (p

+

+

)

)

30

30 b

h2(z / 103)-1. For

typical values of

the baryon density this number is of order unity at recombination

and so we expect baryonic effects to begin appearing in the oscillations

just as they are frozen in.

b

h2(z / 103)-1. For

typical values of

the baryon density this number is of order unity at recombination

and so we expect baryonic effects to begin appearing in the oscillations

just as they are frozen in.

Baryons are conceptually easy to include in the evolution equations since their momentum density provides extra inertia in the joint Euler equation for pressure and potential gradients to overcome. Since inertial and gravitational mass are equal, all terms in the Euler equation save the pressure gradient are multiplied by 1 + R leading to the revised oscillator equation [Hu & Sugiyama, 1995]

|

(16) |

where we have used the fact that the sound speed is reduced by the baryons to cs = 1 / [3(1 + R)]1/2.

To get a feel for the implications of the baryons take the limit

of constant R,  and

and  . Then

d2(R

. Then

d2(R

) /

d

) /

d 2(= 0) may be added to the left hand side to

again put the oscillator equation

in the form of Equation (9) with

2(= 0) may be added to the left hand side to

again put the oscillator equation

in the form of Equation (9) with

+ (1 +

R)

+ (1 +

R) .

The solution then becomes

.

The solution then becomes

|

(17) |

Aside from the lowering of the sound speed which decreases the sound

horizon, baryons have two distinguishing effects:

they enhance the amplitude of the oscillations and shift the equilibrium

point to

= - (1 +

R)

= - (1 +

R) (see

Figure 1b).

These two effects are intimately related

and are easy to understand since the equations are exactly those of

a mass m = 1 + R

on a spring in a constant gravitational field.

For the same initial conditions, increasing the mass causes the oscillator

to fall further in the gravitational field leading to larger oscillations

and a shifted zero point.

(see

Figure 1b).

These two effects are intimately related

and are easy to understand since the equations are exactly those of

a mass m = 1 + R

on a spring in a constant gravitational field.

For the same initial conditions, increasing the mass causes the oscillator

to fall further in the gravitational field leading to larger oscillations

and a shifted zero point.

The shifting of the zero point of the oscillator has significant

phenomenological consequences. Since it is still the effective temperature

+

+

that is the observed

temperature, the zero point shift

breaks the symmetry of the oscillations. The baryons

enhance only the compressional phase, i.e. every other peak. For

the working cosmological model these are the first, third, fifth...

Physically, the extra gravity provided by the baryons enhance

compression into potential wells.

that is the observed

temperature, the zero point shift

breaks the symmetry of the oscillations. The baryons

enhance only the compressional phase, i.e. every other peak. For

the working cosmological model these are the first, third, fifth...

Physically, the extra gravity provided by the baryons enhance

compression into potential wells.

These qualitative results

remain true in the presence of a time-variable R. An additional

effect arises due to the adiabatic damping of an oscillator with

a time-variable mass. Since the energy/frequency of an oscillator

is an adiabatic invariant, the amplitude must decay as

(1 + R)-1/4.

This can also be understood by expanding the time derivatives in

Equation (16) and identifying the

term

as the remnant of the familiar expansion drag on baryon velocities.

term

as the remnant of the familiar expansion drag on baryon velocities.

We have hitherto also been neglecting the energy density of the radiation in

comparison to the matter. The matter-to-radiation ratio scales as

m

/

m

/  r

r

24

24 m

h2(z / 103)-1

and so is also of order unity at recombination for reasonable parameters.

Moreover fluctuations corresponding to the higher peaks entered the

sound horizon at an earlier time, during radiation domination.

m

h2(z / 103)-1

and so is also of order unity at recombination for reasonable parameters.

Moreover fluctuations corresponding to the higher peaks entered the

sound horizon at an earlier time, during radiation domination.

Including the radiation changes the expansion rate of the Universe and hence the physical scale of the sound horizon at recombination. It introduces yet another potential ambiguity in the interpretation of the location of the peaks. Fortunately, the matter-radiation ratio has another effect in the power spectrum by which it can be distinguished. Radiation drives the acoustic oscillations by making the gravitational force evolve with time [Hu & Sugiyama, 1995]. Matter does not.

The exact evolution of the potentials is determined by the relativistic Poisson equation. But qualitatively, we know that the background density is decreasing with time, so unless the density fluctuations in the dominant component grow unimpeded by pressure, potentials will decay. In particular, in the radiation dominated era once pressure begins to fight gravity at the first compressional maxima of the wave, the Newtonian gravitational potential and spatial curvature must decay (see Figure 3).

This decay actually drives the

oscillations: it is timed to leave the fluid maximally compressed with

no gravitational potential to fight as it turns around.

The net effect is doubled since the redshifting from the spatial metric

fluctuation  also goes

away at the same time. When the Universe becomes matter dominated

the gravitational potential is no longer determined by

photon-baryon density perturbations but by the pressureless

cold dark matter. Therefore, the amplitudes of the acoustic peaks

increase as the cold dark matter-to-radiation ratio decreases

[Seljak, 1994,

Hu & Sugiyama, 1995].

Density perturbations in any form of radiation will stop growing around

horizon crossing and lead to this effect. The net result is that across

the horizon scale at matter radiation equality

(keq

also goes

away at the same time. When the Universe becomes matter dominated

the gravitational potential is no longer determined by

photon-baryon density perturbations but by the pressureless

cold dark matter. Therefore, the amplitudes of the acoustic peaks

increase as the cold dark matter-to-radiation ratio decreases

[Seljak, 1994,

Hu & Sugiyama, 1995].

Density perturbations in any form of radiation will stop growing around

horizon crossing and lead to this effect. The net result is that across

the horizon scale at matter radiation equality

(keq  (4 - 2

(4 - 2 2) /

2) /

eq)

the acoustic amplitude increases by a factor of 4-5

[Hu & Sugiyama, 1996].

By eliminating gravitational potentials, photon-baryon acoustic

oscillations eliminate the alternating peak heights from baryon loading.

The observed high third peak

[Halverson et al, 2001]

is a good indication that cold dark matter both exists and dominates the

energy density at recombination.

eq)

the acoustic amplitude increases by a factor of 4-5

[Hu & Sugiyama, 1996].

By eliminating gravitational potentials, photon-baryon acoustic

oscillations eliminate the alternating peak heights from baryon loading.

The observed high third peak

[Halverson et al, 2001]

is a good indication that cold dark matter both exists and dominates the

energy density at recombination.

The photon-baryon fluid has slight imperfections corresponding to shear viscosity and heat conduction in the fluid [Weinberg, 1971]. These imperfections damp acoustic oscillations. To consider these effects, we now present the equations of motion of the system in their full form, including separate continuity and Euler equations for the baryons. Formally the continuity and Euler equations follow from the covariant conservation of the joint stress-energy tensor of the photon-baryon fluid. Because photon and baryon numbers are separately conserved, the continuity equations are unchanged,

|

(18) |

where  b and

vb are the density perturbation and

fluid velocity of the baryons.

The Euler equations contain qualitatively new terms

b and

vb are the density perturbation and

fluid velocity of the baryons.

The Euler equations contain qualitatively new terms

|

(19) |

For the baryons

the first term on the right accounts for cosmological expansion,

which makes momenta decay as a-1. The third term on

the right accounts for momentum exchange in the Thomson scattering

between photons and electrons (protons are very tightly coupled to

electrons via Coulomb scattering), with

ne

ne

T a

the differential Thomson

optical depth, and is compensated by its opposite in the photon Euler

equation. These terms are the origin of heat conduction imperfections.

If the medium is optically thick across a wavelength,

T a

the differential Thomson

optical depth, and is compensated by its opposite in the photon Euler

equation. These terms are the origin of heat conduction imperfections.

If the medium is optically thick across a wavelength,

/ k >> 1

and the photons and baryons cannot slip past each other.

As it becomes optically thin, slippage dissipates the fluctuations.

/ k >> 1

and the photons and baryons cannot slip past each other.

As it becomes optically thin, slippage dissipates the fluctuations.

In the photon Euler equation there is an extra force on the rhs

due to anisotropic stress gradients or radiation viscosity in the

fluid,

. The

anisotropic stress is directly proportional to the

quadrupole moment of the photon temperature distribution.

A quadrupole moment is established by gradients in

v

. The

anisotropic stress is directly proportional to the

quadrupole moment of the photon temperature distribution.

A quadrupole moment is established by gradients in

v as photons from say neighboring temperature crests meet at

a trough (see Plate 3, inset).

However it is destroyed by scattering. Thus

as photons from say neighboring temperature crests meet at

a trough (see Plate 3, inset).

However it is destroyed by scattering. Thus

=

2(kv

=

2(kv /

/

)

Av, where the order

unity constant can be derived from the Boltzmann equation

Av = 16/15

[Kaiser, 1983].

Its evolution is shown in

Figure 3. With

the continuity Equation (7),

kv

)

Av, where the order

unity constant can be derived from the Boltzmann equation

Av = 16/15

[Kaiser, 1983].

Its evolution is shown in

Figure 3. With

the continuity Equation (7),

kv

-3

-3 and

so viscosity takes the form of a damping term.

The heat conduction term can be shown to have a similar effect

by expanding the Euler equations in

k /

and

so viscosity takes the form of a damping term.

The heat conduction term can be shown to have a similar effect

by expanding the Euler equations in

k /  .

The final oscillator equation including both terms becomes

.

The final oscillator equation including both terms becomes

|

(20) |

where the heat conduction coefficient

Ah = R2 / (1 + R).

Thus we expect the

inhomogeneities to be damped by a exponential factor of order

e-k2 /

/

(see

Figure 3).

The damping scale kd is thus of order

(

(see

Figure 3).

The damping scale kd is thus of order

( /

/

)1/2,

corresponding to the geometric mean of the horizon and the mean free path.

Damping can be thought of

as the result of the random walk in the baryons that takes photons

from hot regions into cold and vice-versa

[Silk, 1968].

Detailed numerical integration of the equations

of motion are required to track the rapid growth of the mean free path

and damping length through recombination itself.

These calculations show that the damping scale is of order

kds*

)1/2,

corresponding to the geometric mean of the horizon and the mean free path.

Damping can be thought of

as the result of the random walk in the baryons that takes photons

from hot regions into cold and vice-versa

[Silk, 1968].

Detailed numerical integration of the equations

of motion are required to track the rapid growth of the mean free path

and damping length through recombination itself.

These calculations show that the damping scale is of order

kds*

10

leading to a substantial suppression of the oscillations beyond the

third peak.

10

leading to a substantial suppression of the oscillations beyond the

third peak.

How does this suppression depend on the cosmological parameters? As the

matter density

m

h2 increases, the horizon

m

h2 increases, the horizon

* decreases

since the expansion rate goes up.

Since the diffusion length is proportional to

(

* decreases

since the expansion rate goes up.

Since the diffusion length is proportional to

( *)1/2, it too decreases

as the matter density goes up but not as much as the angular diameter

distance D* which is also inversely

proportional to the expansion rate.

Thus, more matter translates into more damping at a fixed multipole moment;

conversely, it corresponds to slightly less damping at a fixed peak number.

The dependence on baryons is controlled by the mean free path which

is in turn controlled by the free electron density:

the increase in electron density due to an increase in the

baryons is partially offset by a decrease in the ionization fraction due

to recombination. The net result under the Saha approximation is that the

damping length scales approximately as

(

*)1/2, it too decreases

as the matter density goes up but not as much as the angular diameter

distance D* which is also inversely

proportional to the expansion rate.

Thus, more matter translates into more damping at a fixed multipole moment;

conversely, it corresponds to slightly less damping at a fixed peak number.

The dependence on baryons is controlled by the mean free path which

is in turn controlled by the free electron density:

the increase in electron density due to an increase in the

baryons is partially offset by a decrease in the ionization fraction due

to recombination. The net result under the Saha approximation is that the

damping length scales approximately as

( b

h2)-1/4.

Accurate fitting formulae for this scale in terms of

cosmological parameters can be found in

[Hu & White, 1997c].

b

h2)-1/4.

Accurate fitting formulae for this scale in terms of

cosmological parameters can be found in

[Hu & White, 1997c].

The dissipation of the acoustic oscillations leaves a signature in

the polarization of CMB in its wake (see e.g.

[Hu & White, 1997a] and

references therein for a more complete treatment).

Much like reflection off of a surface, Thomson scattering induces

a linear polarization in the scattered radiation.

Consider incoming radiation in the - x direction scattered at right

angles into the z direction (see Plate 2,

left panel).

Heuristically, incoming radiation shakes an electron in the direction

of its electric field vector or polarization

causing it to radiate with an outgoing polarization parallel to that

direction. However since the outgoing polarization

causing it to radiate with an outgoing polarization parallel to that

direction. However since the outgoing polarization

must be orthogonal to the outgoing direction, incoming radiation that

is polarized parallel to the outgoing direction cannot scatter leaving

only one polarization state.

More generally, the Thomson differential

cross section

d

must be orthogonal to the outgoing direction, incoming radiation that

is polarized parallel to the outgoing direction cannot scatter leaving

only one polarization state.

More generally, the Thomson differential

cross section

d T

/ d

T

/ d

|

|  .

.

|2.

|2.

Unlike the reflection of sunlight off of a surface, the incoming

radiation comes from all angles. If it were completely isotropic in

intensity, radiation coming along the

would

provide the polarization state that is missing from that coming along

would

provide the polarization state that is missing from that coming along

leaving the net outgoing radiation unpolarized.

Only a quadrupole temperature anisotropy in the radiation

generates a net linear polarization from Thomson scattering.

As we have seen, a quadrupole

can only be generated causally by the motion of photons and then only

if the Universe is optically thin to Thomson

scattering across this scale (i.e. it is inversely proportional to

leaving the net outgoing radiation unpolarized.

Only a quadrupole temperature anisotropy in the radiation

generates a net linear polarization from Thomson scattering.

As we have seen, a quadrupole

can only be generated causally by the motion of photons and then only

if the Universe is optically thin to Thomson

scattering across this scale (i.e. it is inversely proportional to

).

Polarization generation suffers

from a Catch-22: the scattering which generates polarization also

suppresses its quadrupole source.

).

Polarization generation suffers

from a Catch-22: the scattering which generates polarization also

suppresses its quadrupole source.

The fact that the polarization strength is of order the quadrupole

explains the shape and height of the polarization spectra in

Plate 1b.

The monopole and dipole

and

v

and

v are of the same order of magnitude

at recombination, but their oscillations are

are of the same order of magnitude

at recombination, but their oscillations are

/ 2 out of phase as follows from

Equation (9) and Equation (10). Since the quadrupole is of order

kv

/ 2 out of phase as follows from

Equation (9) and Equation (10). Since the quadrupole is of order

kv /

/  (see Figure 3), the polarization

spectrum should be smaller than the temperature spectrum by a factor of

order k /

(see Figure 3), the polarization

spectrum should be smaller than the temperature spectrum by a factor of

order k /  at recombination. As in the case of the damping, the precise value requires

numerical work

[Bond & Efstathiou, 1987]

since

at recombination. As in the case of the damping, the precise value requires

numerical work

[Bond & Efstathiou, 1987]

since  changes so

rapidly near recombination. Calculations show

a steady rise in the polarized fraction with increasing l or

k to a maximum of about ten percent before damping destroys the

oscillations and hence the dipole source. Since

v

changes so

rapidly near recombination. Calculations show

a steady rise in the polarized fraction with increasing l or

k to a maximum of about ten percent before damping destroys the

oscillations and hence the dipole source. Since

v is out of

phase with the monopole, the polarization peaks should also be out of

phase with the temperature peaks. Indeed,

Plate 1b shows that this is the case.

Furthermore, the phase relation also tells us that the polarization is

correlated with the temperature perturbations. The correlation power

C

is out of

phase with the monopole, the polarization peaks should also be out of

phase with the temperature peaks. Indeed,

Plate 1b shows that this is the case.

Furthermore, the phase relation also tells us that the polarization is

correlated with the temperature perturbations. The correlation power

C

E

being the product of the two, exhibits oscillations at twice the

acoustic frequency.

E

being the product of the two, exhibits oscillations at twice the

acoustic frequency.

Until now, we have focused on the polarization strength without regard to its orientation. The orientation, like a 2 dimensional vector, is described by two components E and B. The E and B decomposition is simplest to visualize in the small scale limit, where spherical harmonic analysis coincides with Fourier analysis [Seljak, 1997]. Then the wavevector k picks out a preferred direction against which the polarization direction is measured (see Plate 2, right panel). Since the linear polarization is a "headless vector" that remains unchanged upon a 180° rotation, the two numbers E and B that define it represent polarization aligned or orthogonal with the wavevector (positive and negative E) and crossed at ± 45° (positive and negative B).

In linear theory, scalar perturbations like the gravitational potential and temperature perturbations have only one intrinsic direction associated with them, that provided by k, and the orientation of the polarization inevitably takes it cue from that one direction, thereby producing an E -mode. The generalization to an all-sky characterization of the polarization changes none of these qualitative features. The E -mode and the B -mode are formally distinguished by the orientation of the Hessian of the Stokes parameters which define the direction of the polarization itself. This geometric distinction is preserved under summation of all Fourier modes as well as the generalization of Fourier analysis to spherical harmonic analysis.

The acoustic peaks in the polarization appear exclusively in the EE power spectrum of Equation (5). This distinction is very useful as it allows a clean separation of this effect from those occuring beyond the scope of the linear perturbation theory of scalar fluctuations: in particular, gravitational waves (see Section 4.2.3) and gravitational lensing (see Section 4.2.4). Moreover, in the working cosmological model, the polarization peaks and correlation are precise predictions of the temperature peaks as they depend on the same physics. As such their detection would represent a sharp test on the implicit assumptions of the working model, especially its initial conditions and ionization history.

The discussion in the previous sections suffices for a qualitative understanding of the acoustic peaks in the power spectra of the temperature and polarization anisotropies. To refine this treatment we must consider more carefully the sources of anisotropies and their projection into multipole moments.

Because the description of the acoustic oscillations takes place

in Fourier space, the projection of inhomogeneities at recombination

onto anisotropies today has an added level of complexity.

An observer today sees the acoustic oscillations

in effective temperature as they appeared on a spherical shell at

x = D*

at recombination, where

at recombination, where

is the direction vector,

and D* =

is the direction vector,

and D* =

0 -

0 -

* is

the distance light can travel between recombination and the present

(see Plate 3).

Having solved for the Fourier amplitude

[

* is

the distance light can travel between recombination and the present

(see Plate 3).

Having solved for the Fourier amplitude

[ +

+

](k,

](k,

*), we can expand the

exponential in Equation (6) in terms of spherical harmonics, so the

observed anisotropy today is

*), we can expand the

exponential in Equation (6) in terms of spherical harmonics, so the

observed anisotropy today is

|

(21) |

where the projected source

a (k) =

[

(k) =

[ +

+

](k,

](k,

*)

j

*)

j (kD*).

Because the spherical harmonics are orthogonal, Equation (1) implies that

(kD*).

Because the spherical harmonics are orthogonal, Equation (1) implies that

m today is given by the

integral in square brackets today.

A given plane wave actually produces a range of anisotropies in

angular scale as is obvious from Plate 3. The

one-to-one mapping between wavenumber and multipole moment described in

Section 3.1

is only approximately true and comes from the fact that the

spherical Bessel function

j

m today is given by the

integral in square brackets today.

A given plane wave actually produces a range of anisotropies in

angular scale as is obvious from Plate 3. The

one-to-one mapping between wavenumber and multipole moment described in

Section 3.1

is only approximately true and comes from the fact that the

spherical Bessel function

j (kD*) is strongly peaked

at kD*

(kD*) is strongly peaked

at kD*

. Notice that this peak

corresponds to contributions in the direction orthogonal to the

wavevector where the correspondence

between

. Notice that this peak

corresponds to contributions in the direction orthogonal to the

wavevector where the correspondence

between  and k is

one-to-one (see Plate 3).

and k is

one-to-one (see Plate 3).

|

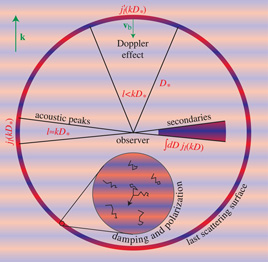

Plate 3. Integral approach. CMB anisotropies can be thought of as the line-of-sight projection of various sources of plane wave temperature and polarization fluctuations: the acoustic effective temperature and velocity or Doppler effect (see Section 3.8), the quadrupole sources of polarization (see Section 3.7) and secondary sources (see Section 4.2, Section 4.3). Secondary contributions differ in that the region over which they contribute is thick compared with the last scattering surface at recombination and the typical wavelength of a perturbation. |

Projection is less straightforward for other sources of anisotropy.

We have hitherto neglected the fact that the acoustic motion of

the photon-baryon fluid also produces a Doppler shift in the radiation

that appears to the observer as a temperature anisotropy as well.

In fact, we argued above that

vb  v

v is

of comparable magnitude but out of phase with the effective temperature.

If the Doppler effect projected in the same way as the effective

temperature,

it would wash out the acoustic peaks. However, the Doppler effect has

a directional dependence as well since it is only the line-of-sight

velocity that produces the effect. Formally, it is a dipole source

of temperature anisotropies and hence has an

is

of comparable magnitude but out of phase with the effective temperature.

If the Doppler effect projected in the same way as the effective

temperature,

it would wash out the acoustic peaks. However, the Doppler effect has

a directional dependence as well since it is only the line-of-sight

velocity that produces the effect. Formally, it is a dipole source

of temperature anisotropies and hence has an

= 1 structure.

The coupling of the dipole and plane wave angular momenta

imply that in the projection of the Doppler effect involves a

combination of j

= 1 structure.

The coupling of the dipole and plane wave angular momenta

imply that in the projection of the Doppler effect involves a

combination of j ±1 that may be rewritten as

j

±1 that may be rewritten as

j '(x)

'(x)

dj

dj (x) / dx.

The structure of j

(x) / dx.

The structure of j ' lacks a strong peak

at x =

' lacks a strong peak

at x =  .

Physically this corresponds to the fact that the

velocity is irrotational and hence has no component in the direction

orthogonal to the wavevector (see Plate 3).

Correspondingly, the Doppler effect cannot produce strong peak structures

[Hu & Sugiyama, 1995].

The observed peaks must be acoustic peaks in the

effective temperature not "Doppler peaks".

.

Physically this corresponds to the fact that the

velocity is irrotational and hence has no component in the direction

orthogonal to the wavevector (see Plate 3).

Correspondingly, the Doppler effect cannot produce strong peak structures

[Hu & Sugiyama, 1995].

The observed peaks must be acoustic peaks in the

effective temperature not "Doppler peaks".

There is one more subtlety involved when passing from acoustic oscillations

to anisotropies. Recall from

Section 3.5 that radiation leads to decay of the

gravitational potentials. Residual radiation after decoupling therefore

implies that the effective temperature is not precisely

[ +

+

](

]( *).

The photons actually have slightly shallower potentials to climb out of and

lose the perturbative analogue of the cosmological redshift, so the

[

*).

The photons actually have slightly shallower potentials to climb out of and

lose the perturbative analogue of the cosmological redshift, so the

[ +

+

](

]( *) overestimates the difference between

the true photon temperature

and the observed temperature. This effect of course is already in the

continuity equation for the monopole Equation (18) and

so the source in Equation (21) gets generalized to

*) overestimates the difference between

the true photon temperature

and the observed temperature. This effect of course is already in the

continuity equation for the monopole Equation (18) and

so the source in Equation (21) gets generalized to

|

(22) |

The last term vanishes for constant gravitational potentials, but is

non-zero if residual radiation driving exists, as it will in low

m

h2 models.

Note that residual radiation driving is particularly important because

it adds in phase with the monopole: the potentials vary in time only

near recombination, so the Bessel function can be set to

jl(kD*) and removed from the

m

h2 models.

Note that residual radiation driving is particularly important because

it adds in phase with the monopole: the potentials vary in time only

near recombination, so the Bessel function can be set to

jl(kD*) and removed from the

integral. This

complication has the effect of decreasing the multipole value of

the first peak

integral. This

complication has the effect of decreasing the multipole value of

the first peak  1

as the matter-radiation ratio at recombination decreases

[Hu & Sugiyama, 1995].

Finally, we mention that time varying potentials can also play a role at

very late times due to non-linearities or the importance of a

cosmological constant for example.

Those contributions, to be discussed more in

Section 4.2.1, are sometimes referred

to as late Integrated Sachs-Wolfe effects, and do not add

coherently with

[

1

as the matter-radiation ratio at recombination decreases

[Hu & Sugiyama, 1995].

Finally, we mention that time varying potentials can also play a role at

very late times due to non-linearities or the importance of a

cosmological constant for example.

Those contributions, to be discussed more in

Section 4.2.1, are sometimes referred

to as late Integrated Sachs-Wolfe effects, and do not add

coherently with

[ +

+

](

]( *).

*).

Putting these expressions together and squaring, we obtain the power spectrum of the acoustic oscillations

|

(23) |

This formulation of the anisotropies in terms of projections of sources with specific local angular structure can be completed to include all types of sources of temperature and polarization anisotropies at any given epoch in time linear or non-linear: the monopole, dipole and quadrupole sources arising from density perturbations, vorticity and gravitational waves [Hu & White, 1997b]. In a curved geometry one replaces the spherical Bessel functions with ultraspherical Bessel functions [Abbott & Schaefer, 1986, Hu et al, 1998]. Precision in the predictions of the observables is then limited only by the precision in the prediction of the sources. This formulation is ideal for cases where the sources are governed by non-linear physics even though the CMB responds linearly as we shall see in Section 4.

Perhaps more importantly, the widely-used CMBFAST code

[Seljak & Zaldarriaga, 1996]

exploits these properties to calculate the anisotropies in linear

perturbation efficiently. It numerically solves for

the smoothly-varying sources on a sparse grid in wavenumber,

interpolating in the integrals for a handful of

's in the

smoothly varying C

's in the

smoothly varying C . It has largely replaced the original

ground breaking codes

[Wilson & Silk, 1981,

Bond & Efstathiou, 1984,

Vittorio & Silk, 1984]

based on tracking the rapid temporal oscillations of the multipole moments

that simply reflect structure in the spherical Bessel

functions themselves.

. It has largely replaced the original

ground breaking codes

[Wilson & Silk, 1981,

Bond & Efstathiou, 1984,

Vittorio & Silk, 1984]

based on tracking the rapid temporal oscillations of the multipole moments

that simply reflect structure in the spherical Bessel

functions themselves.

The phenomenology of the acoustic peaks in the temperature and polarization

is essentially described by 4 observables and the initial conditions

[Hu et al, 1997].

These are the angular extents of the sound horizon

a

a

D*

/ s*,

the particle horizon at matter radiation equality

D*

/ s*,

the particle horizon at matter radiation equality

eq

eq

keq

D* and the damping scale

keq

D* and the damping scale

d

d

kd

D* as well as the value of the baryon-photon

momentum density ratio R*.

kd

D* as well as the value of the baryon-photon

momentum density ratio R*.

a sets the

spacing between of the peaks;

a sets the

spacing between of the peaks;

eq and

eq and

d compete to

determine their

amplitude through radiation driving and diffusion damping.

R* sets the

baryon loading and, along with the potential well depths set by

d compete to

determine their

amplitude through radiation driving and diffusion damping.

R* sets the

baryon loading and, along with the potential well depths set by

eq,

fixes the modulation of the even and odd peak heights.

The initial conditions set the phase, or equivalently the location of

the first peak in units of

eq,

fixes the modulation of the even and odd peak heights.

The initial conditions set the phase, or equivalently the location of

the first peak in units of

a, and an overall

tilt n in the power spectrum.

a, and an overall

tilt n in the power spectrum.

In the model of Plate 1, these numbers

are  a = 301

(

a = 301

( 1 =

0.73

1 =

0.73 a),

a),

eq = 149,

eq = 149,

d = 1332,

R* = 0.57 and n = 1 and in this family

of models the parameter sensitivity is approximately

[Hu et al, 2001]

d = 1332,

R* = 0.57 and n = 1 and in this family

of models the parameter sensitivity is approximately

[Hu et al, 2001]

|

(24) |

and  R* / R*

R* / R*

1.0

1.0

b

h2 /

b

h2 /

b

h2. Current observations indicate that

b

h2. Current observations indicate that

a = 304 ± 4,

a = 304 ± 4,

eq = 168 ±

15,

eq = 168 ±

15,  d = 1392

± 18, R* = 0.60 ± 0.06, and

n = 0.96 ± 0.04

([Knox et al, 2001];

see also

[Wang et al, 2001,

Pryke et al, 2001,

de Bernardis et al, 2001]),

if gravitational waves contributions

are subdominant and the reionization redshift is low as

assumed in the working cosmological model (see

Section 2.1).

d = 1392

± 18, R* = 0.60 ± 0.06, and

n = 0.96 ± 0.04

([Knox et al, 2001];

see also

[Wang et al, 2001,

Pryke et al, 2001,

de Bernardis et al, 2001]),

if gravitational waves contributions

are subdominant and the reionization redshift is low as

assumed in the working cosmological model (see

Section 2.1).

The acoustic peaks therefore contain three rulers for the angular

diameter distance test for curvature, i.e. deviations from

tot = 1.

However contrary to popular belief, any one of these alone is not

a standard ruler whose absolute scale is known even in the

working cosmological model. This is reflected in the sensitivity of

these scales to other cosmological parameters.

For example, the dependence of

tot = 1.

However contrary to popular belief, any one of these alone is not

a standard ruler whose absolute scale is known even in the

working cosmological model. This is reflected in the sensitivity of

these scales to other cosmological parameters.

For example, the dependence of

a on

a on

m

h2 and hence the Hubble

constant is quite strong. But in combination with a measurement of

the matter-radiation ratio from

m

h2 and hence the Hubble

constant is quite strong. But in combination with a measurement of

the matter-radiation ratio from

eq, this

degeneracy is broken.

eq, this

degeneracy is broken.

The weaker degeneracy of

a on the baryons

can likewise be broken from a measurement of the baryon-photon ratio

R*. The damping scale

a on the baryons

can likewise be broken from a measurement of the baryon-photon ratio

R*. The damping scale

d provides an

additional consistency check on the implicit assumptions in the working

model, e.g. recombination and the energy contents

of the Universe during this epoch. What makes the peaks so valuable

for this test is that the rulers are standardizeable and contain

a built-in consistency check.

d provides an

additional consistency check on the implicit assumptions in the working

model, e.g. recombination and the energy contents

of the Universe during this epoch. What makes the peaks so valuable

for this test is that the rulers are standardizeable and contain

a built-in consistency check.

There remains a weak but perfect

degeneracy between

tot and

tot and

because they both appear only in D*.

This is called the angular diameter distance degeneracy in the

literature and can readily be generalized to dark energy components beyond

the cosmological constant assumed here. Since the effect of

because they both appear only in D*.

This is called the angular diameter distance degeneracy in the

literature and can readily be generalized to dark energy components beyond

the cosmological constant assumed here. Since the effect of

is

intrinsically so small, it only creates a correspondingly small

ambiguity in

is

intrinsically so small, it only creates a correspondingly small

ambiguity in

tot for

reasonable values of

tot for

reasonable values of

.

The down side is that dark energy can never be isolated through the peaks

alone since it only takes a small amount of curvature to mimic its effects.

The evidence for dark energy through the CMB comes about by allowing

for external information. The most important is the nearly overwhelming

direct evidence for

.

The down side is that dark energy can never be isolated through the peaks

alone since it only takes a small amount of curvature to mimic its effects.

The evidence for dark energy through the CMB comes about by allowing

for external information. The most important is the nearly overwhelming

direct evidence for

m < 1

from local structures in the Universe.

The second is the measurements of a relatively high Hubble constant

h

m < 1

from local structures in the Universe.

The second is the measurements of a relatively high Hubble constant

h  0.7;

combined with a relatively low

0.7;

combined with a relatively low

m

h2 that is preferred in the CMB data, it implies

m

h2 that is preferred in the CMB data, it implies

m < 1

but at low significance currently.

m < 1

but at low significance currently.

The upshot is that precise measurements of the acoustic peaks

yield precise determinations of four fundamental parameters of the

working cosmological model:

b

h2,

b

h2,

m

h2, D*, and n. More

generally, the first three can be replaced by

m

h2, D*, and n. More

generally, the first three can be replaced by

a,

a,

eq,

eq,

d and

R*

to extend these results to models where the underlying assumptions of the

working model are violated.

d and

R*

to extend these results to models where the underlying assumptions of the

working model are violated.

2 Recall that the comoving

scale k does not vary with time. At very early times, then, the

wavelengh k-1 is much larger than the horizon

.

Back.

.

Back.