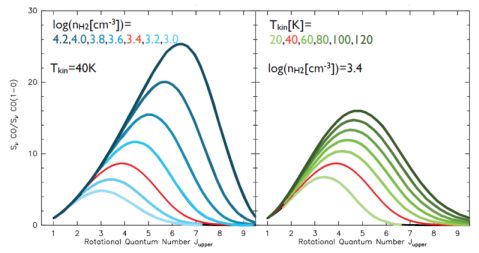

As noted in Sec. 2.6 the excitation of molecular gas in high–redshift galaxies provides important information regarding the average physical properties of the gas, in particular its temperature and density. This is illustrated in Fig. 3 where the expected CO excitation is shown as a function of density and temperature. One important caveat is that typically only galaxy–integrated line fluxes can be measured at high redshift. These measurements are then fed into LVG (Sec. 2.6.1) or PDR/XDR (Sec. 2.6.2) models that assume that the line emission is emerging from the same cloud/volume (i.e. that they share the same physical conditions). The validity of this assumption is questionable, as it is known that the different rotational transitions have different critical densities: the higher–J transitions need much higher densities than the low–J ones to be excited. This situation complicates further if unresolved measurements of high–density tracers (e.g. HCN, HCO+) are added to the ‘single component' models. Another caveat is that the molecular gas excitation measurements in high redshift galaxies are typically restricted to the mid–J levels of CO emission.

|

Figure 3. This figure illustrates how the measured CO emission ladder changes as a function of temperature and density (adopted from Weiß et al. (2007). The left panel shows the effect of changing density at fixed temperature (Tkin = 40 K. The right panel shows the effect of varying kinetic temperatures for a fixed density (log(n(H2)) = 3.4). Both panels have been normalized to the CO(1–0) transition. High CO excitation is achieved through a combination of high kinetic temperature and high density. Given the typically sparsely sampled CO excitation and large error bars in high redshift observations, this degeneracy can not be easily broken observationally. Additional information, such as independent estimates of the kinetic temperature through [C I] or dust measurements can help to break this degeneracy. Note that increased temperatures lead to a broader CO emission ladder, as more and more high–J levels are populated following the Boltzmann distribution. |

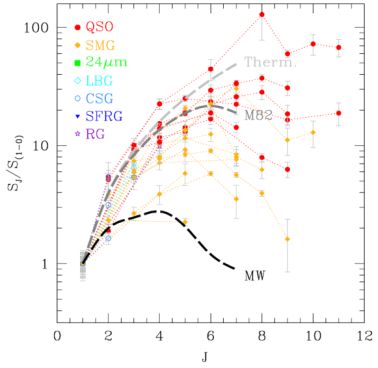

With these caveats in mind there are a number of important results emerging from high–redshift CO excitations analyses. The main result is that the different source populations at high redshift show distinctly different excitation (see compilation of all high–redshift CO excitation in Fig. 4). The CO excitation of quasar host galaxies can in essentially all cases be modeled by a simple model with one temperature and density out to the highest–J CO transition with a typical gas density of log(n(H2)[cm−3]) = 3.6 – 4.3, and temperatures of Tkin = 40−60 K. A prominent example is the highly excited quasar host APM 08279+5255 (Weiß et al. 2007a). Measurements of the CO ground transition in a number of quasar host galaxies (Riechers et al. 2011a) have shown that the measured CO(1–0) flux is what was expected based on a single–component extrapolation from higher–J CO transitions, i.e. there is no excess of CO(1–0) emission in these sources (Riechers et al. 2006a, 2011a). One interpretation of this finding is that the molecular gas emission comes from a very compact region in the centre of the quasar host, which is confirmed by the few (barely) resolved measurements of quasar hosts (Sec. 4.6). It should be noted though that there is recent evidence that an additional high–excitation component, likely related to the AGN itself, is needed to explain the elevated high–J line fluxes in some sources, e.g. PSS 2322+1944 (Weiß et al., in prep.) and J 1148+5251 (Riechers et al., in prep.).

|

Figure 4. CO emission ladder of all sources where the CO(1–0) line has been measured. The CO line flux is shown as a function of rotational quantum number and the colors indicate the different source types. Measurements for individual sources are connected by a dashed line. The line fluxes have been normalized to the CO(1–0) line. The QSOs are the most excited systems found, with an average peak of the CO ladder at around J ∼ 6. This is consistent with the high star formation rate and compact emission regions in their host galaxies. The SMGs are slightly less excited on average, and their CO emission ladder peak around J ∼ 5. The dashed thick lines indicate template CO emission ladders for the Milky Way (black) and M 82 (grey). The dashed dark grey line shows constant brightness temperature on the Rayleigh–Jeans scale, i.e. S ∼ ν2 (note that this approximation is not valid for high J). |

The submillimeter galaxies, on the other hand, show (i) less excited molecular gas, and (ii) excess emission in the CO(1–0) ground transition. This is again illustrated in Fig. 4, where the orange symbols of the SMGs are on average at lower fluxes compared to the quasars (red symbols). On average, the typical density of SMGs is log(n(H2)[cm−3]) = 2.7-3.5, and temperatures are in the range of Tkin = 30 − 50 K. Observations in the CO(1–0) line of a few SMGs have furthermore demonstrated that an additional cold component is needed to explain the observed excitation (Ivison et al. 2011, Riechers et al. 2011b). This implies that the total gas mass of the SMGs is underestimated if mid–J CO transitions are used to calculate masses assuming constant brightness temperature (see Sec. 4.2). A few SMGs have been resolved spatially and show more extended emission in the ground transition than in higher transitions (Ivison et al. 2011; although cf. Hodge et al. 2012).

Up to the mid–J measurements available for high redshift sources the CO excitation of the SMGs and QSOs roughly follow those of the centres of nearby starburst galaxies (e.g., M 82: Mao et al. 2000; Ward et al. 2003, see dashed line in Fig. 4; NGC 253: Bradford et al. 2003; Bayet et al. 2004, and Henize 2-10: Bayet et al. 2004). It should be noted that the excitation in Galactic molecular cloud cores can be equally high (e.g. Habart et al. 2010, Leurini et al. 2012; van Kempen et al. 2010, Manoj et al. 2012). However, in Galactic clouds such very high excitation is only seen in pc scales cloud cores, while in nearby starburst nuclei high excitation is seen on scales of order 100 pc scales, and for high–redshift galaxies the scale can extend to a few kpc.

As stated in Sec. 3, the seperation between SMGs and QSO host galaxies is largely due to historical selection effects and there are sources that fullfill both definitions. The different excitation conditions in the two groups however argue that broadly speaking gas–rich quasars and SMGs represent different stages of galaxy evolution, with the quasars being more compact and harboring more highly excited gas than the SMGs. In a simplistic picture, the quasars could be the result of a merger, in which the molecular gas concentrates in the centre of the potential well, while the SMGs would then constitute merging systems that have not fully coalesced. The latter is supported by the fact that high–resolution observations of many SMGs show multiple emission components (e.g. Engel et al. 2010, Tacconi et al. 2010). SMGs and quasars also show similar clustering properties (Hickox et al. 2012).

To date, only a few excitation measurements exist for the CSGs (Dannerbauer et al. 2009; Aravena et al. 2010), and only up to CO 3-2. In the case of BzK-21000 Dannerbauer et al. (2009) showed that the J = 3 emission must be significantly subthermally excited, resembling more that of the Milky Way than the higher–excitation systems discussed above. These CSGs have lower star formation rates than found in the quasars and SMGs, and have large ( ∼ 10 kpc) sizes – the combination of these apparently leads to a less extreme gas excitation than found in the hyper-starburst galaxies at high redshift. Observations of higher order CO transitions are required in these systems.

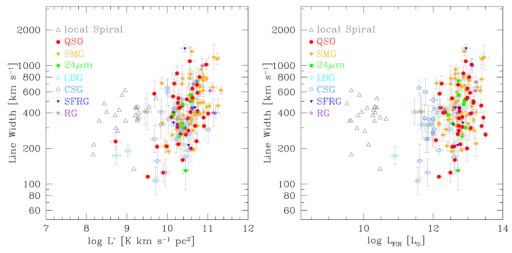

Bothwell et al. (2012) suggest that there is a correlation between CO luminosity and line width in high redshift starbursts, likely relating to baryon-dominated gas dynamics within the regions probed. In Fig. 5, we plot the CO line widths (FWHM) vs. CO luminosity for a broader range of CO detected distant galaxy types. Considering only the hyperstarbursts (SMGs and quasar hosts), both occupy similar parameters space in this diagram, and there is no significant correlation between CO luminosity and linewidth. However, the CSG clearly segregate to smaller line widths relative to SMGs, by about a factor ∼ two, and, while the scatter is large, the median CO luminosity for CSGs is smaller by a similar factor.

|

Figure 5. The CO line width (FWHM) versus CO line luminosity (left) and versus the FIR luminosity (right panel). Note that the CSG show systematically lower line widths for a given CO line luminosity than the hyper–starburst quasar hosts and SMGs (we have corrected the vrot, max values given in Tacconi et al. (2010) to give accurate FWHM values). The grey datapoints show local spiral galaxies (with stellar masses > 1010 M⊙ from the HERACLES/THINGS surveys (Leroy et al. 2008, Walter et al. 2008). The local FWHM values are corrected for inclination, the high–z values are not (in the absence of unknown inclinations). |

4.2. CO luminosity to total molecular gas mass conversion

Until a few years ago, the standard practice for high redshift galaxies was to use the starburst conversion factor to derive gas masses. This practice was justified in part on the extreme luminosities, high inferred gas densities based on CO excitation, and in some cases on the direct observation of compact star forming regions (scales ∼ 2−4 kpc; Tacconi et al. 2008, Momjian et al. 2007, Ivison et al. 2010a, 2012, Carilli et al. 2002, Walter et al. 2009). Also, in some cases it appeared that, like nearby nuclear starbursts, the gas mass exceeded the dynamical mass when using a Milky Way conversion factor (Solomon et al. 1997, Tacconi et al. 2008, Carilli et al. 2011, Walter et al. 2004, Riechers et al. 2008, 2009).

As other populations of galaxies are now being detected in CO emission at high redshift, such as color–selected star forming galaxies (Sec. 3.5), the question of the conversion factor has become paramount. The last few years have seen a few attempts at the first direct measurements of the CO luminosity to gas mass conversion factor.

A minimum α can be derived assuming optically thin emission,

and adopting a Boltzmann distribution for the population of states. In

this case, the CO(1–0) luminosity, LCO(1−0),

simply counts the number of molecules in the J = 1 state via:

NJ=1 = LCO(1−0) / (A

× hν), where A is the Einstein A coefficient

(6 × 10−8 s−1), and ν =

115 GHz. The total number of CO molecules is then determined by the

partition function, ie. the relative fraction in the J = 1 state, which

we designate f. For example at T = 10, 20, and 40 K, f = 0.47, 0.31, and

0.19, respectively. One can then convert to total number of

H2 molecules assuming a CO/H2 abundance ratio,

which for Galactic GMCs is 10−4. Multiplying by the

mass of an H2 molecule, and

including a factor 1.36 for the Helium abundance, leads to the total

gas mass. Converting to the relevant units, leads to: α =

(0.09 / f) M⊙ [K km s−1

pc2]−1, at z = 0.

1

Tacconi et al. (2008)

use spatially resolved spectral imaging to

derive either virial or rotational masses for a sample of SMGs and

color selected galaxies. Galaxy sizes are estimated from the CO

imaging and/or optical or near–IR imaging (see also

Neri et al. 2003;

Thomson et al. 2012).

Tacconi et al. compare the dynamical masses

with the sum of the gas mass (modulo α) and stellar mass

(derived from near–IR photometry), including a small correction (10%

to 20%) for dark matter. They conclude that for the SMGs, the value

of α is most likely close to the starburst value (α ∼

1), while for the CSG a value α ∼ 4.8 is favored.

Daddi et al. (2010)

have performed a similar analysis on CSGs, based

on (marginally) spatially resolved imaging with the PdBI of CO 2–1

emission of a sample of three z ∼ 1.5 sBzK galaxies. Their

dynamical analysis is guided by numerical simulations of clumpy,

turbulent disks, to allow for significant non–circular motions

(Bournaud et al. 2009).

They find that the measurements are consistent with αCO

= 3.6 ± 0.8 M⊙ / (K km s−1

pc2).

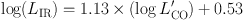

The best rotational dynamical analysis of an SMG to date is the JVLA

observation of GN 20 at z = 4.0 (Fig. 7)

by Hodge et al.

(2012;

see Sec. 4.6). They show that the CO(2–1)

emission is well characterized by a rotating disk of 7 kpc radius

with a large rotation velocity of 575 ± 100 km

s−1 and internal velocity dispersion of 100 km

s−1. They derive a dynamical mass of 5.4 ± 2.4

× 1011 M⊙. Subtracting

the stellar mass, including a 15% dark matter contribution leads to

α ∼ 1 M⊙ / (K km s−1

pc2).

The main uncertainties in the dynamical analysis are the current crude

estimates of the dynamical masses based on marginally resolved imaging

data, and the standard pit–falls in estimating the stellar masses

based on SED fitting, in particular for starburst–type systems

(Ivison et al. 2011).

Magdis et al. (2011)

use a metallicity–dependent dust–to–gas ratio

approach to estimate αCO. They analyze two galaxies in the

GOODS–N deep field with excellent rest–frame IR SEDs, one SMG

(GN 20), and one CSG

(BzK-21000). From these, and using the

Draine & Li (2007)

dust models, they derive a dust mass for each source. Metallicities are

derived from the stellar mass – metallicity relation for the CSG

(Erb et al. 2006),

and a starburst model for GN 20. They then use the

Solomon et al. (1997)

metallicity dependent dust to gas relation to obtain an estimate of the

gas masses of 9 × 1010 M⊙ for the CSG

and 1.5 × 1011 M⊙ for the SMG. Comparing

these masses to the CO(1–0) luminosities leads to α

≤ 1.0 for the SMG, while for the CSSGF they find α

∼ 4, consistent with earlier estimates. These results have been

generalized in the more comprehensive study by

Magdis et al. (2012b).

Ivison et al. (2011)

take two different approaches to derive

molecular gas masses, and hence infer α in SMGs. First, they

propose a model in which some fraction of the CO emission occurs at

the ‘Eddington limit' in dense star forming regions (a

‘maximal starburst'), ie. a self–gravitating disk supported by

starburst–driven radiation pressure on the dust grains

(Thompson et al. 2005;

Thompson 2009;

Krumholz & Thompson

2012).

Thompson (2009)

derive a maximum star formation efficiency in this case of:

SFEmax ≡ LIR /

Mgas < 500 L⊙

M⊙−1, and an areal star formation

rate density of 1000 M⊙ yr−1

kpc−2. This maximum surface density is seen to hold on

scales from star forming cloud cores in GMCs ( ∼ 1pc) to the nuclear

starburst regions of low–z ULIRGs.

Ivison et al. then make a correction to the total gas for the fraction

of cold, quiescent gas not involved in active star formation based on

the CO excitation. Under these assumptions, the molecular gas mass

can be estimated from the IR luminosity. For 4 of their 5 SMGs, the

values are between α = 0.4 and 0.7, while for the last source

the value is 3.7. This latter source also has by far the lowest CO

excitation.

Second,

Ivison et al. (2011)

use radiative transfer modeling to

derive physical conditions within the clouds, and infer gas masses in

a manner analogous to the low redshift ULIRG analysis of

Downes & Solomon

(1998).

Unfortunately, LVG models have a fundamental

degeneracy between density, temperature, and non–virial gas

kinematics, when using just CO excitation

(Sec. 2.6.1). They find the CO SEDs

are consistent with either α ∼ 4.5 in cold, dense gas

with large non–virial motions, or α ∼ 1 in warm,

more diffuse gas closer to virial dynamics.

Genzel et al. (2012)

consider the effect of metallicity

on the conversion factor α in a sample of CSG at z ∼ 1

to 2. They have obtained estimates for the metallicities from optical

[N II]/Hα measurements. They find that

galaxies with similar

sizes, SFRs, and dynamical masses, but different metallicities (and

stellar masses; Erb et al.), show very different star formation

efficiencies, with the CO to FIR luminosity ratio decreasing

dramatically with decreasing metallicity, at fixed FIR luminosity. If

α is the same in each system, then this would imply a much

shorter gas consumption timescale (gas mass/SFR) in low metallicity

galaxies vs. high metallicity galaxies.

Alternatively,

Genzel et al. (2012)

propose adopting a standard star

formation efficiency relating gas mass to star formation rate

(Sec. 4.5). In this case, the decrease in CO

luminosity is not due to a lower gas mass but an increase in α at low

metallicity. Such a trend is expected and observed at low metallicity

in nearby galaxies (Sec. 2.5), since

dust shielding becomes less efficient, and CO in molecular cloud

envelopes are photo–dissociated much more deeply into the cloud

(Leroy et al. 2011;

Bolatto et al. 2013,

Schruba et al. 2012).

Genzel et al. 2012;

Stacey et al. 1991)

derive the empirical relationship: log(αCO) = 12

− 1.3 × [12 + log(O/H)]. The implication is

that stars can form in CO–poor molecular gas, and that the expected

CO luminosities of low metallicity galaxies at high redshift are lower

than previously predicted based on standard α values

(Glover & Clark

2012;

Papadopoulos &

Pelupessy 2010).

Magnelli et al. (2012)

perform a similar analysis of the conversion

factor based on dust-to-gas ratios, for a mixed sample of SMGs and CSG

at z = 1 to 4. They adopt a similar dust mass calculation based on

the FIR luminosity, and a metallicity-dependent dust-to-gas ratio as in

Genzel et al. (2012).

Their results are consistent with a low value of

α for starbursts, and a factor five higher value for CSG. They

also find a trend of decreasing α with increasing dust

temperature, and while the trend may be continuous, they recommend

that for a dust temperatures < 30K, a Milky Way conversion factor is

appropriate, while for higher dust temperatures the starburst value

should be used, at least for solar metallicity systems.

Many conclusions in astronomy are not based on a single,

absolutely compelling direct measurement, but on a series of

measurements, modeling, and consistency arguments from which the

weight of evidence leads to a ‘concordance model'. This approach

applies to the the CO–to–gas mass conversion factor in distant

galaxies. The current measurements of αCO are principally

based on dynamical imaging and modeling, dust–to–gas

measurements, radiative transfer modeling, and most recently, on star

formation efficiencies. These measurements suggest a nuclear starburst value

∼ 0.8 M⊙ / (K km s−1

pc2)−1 for SMGs and quasar

hosts, and a Milky Way GMC value of αCO ∼ 4

M⊙ / (K km s−1

pc2)−1 in CSG, with a likely further

increase in low metallicity galaxies. These values are consistent with the

generally extended, clumpy disk–like CO distribution, lower CO

excitation, and Milky Way CO/FIR (FIR derived from SFR) ratios in CSG,

compared to the often (although not exclusively) more compact,

merger–like morphologies, higher excitation, and starburst CO/FIR

ratios in SMGs and quasars.

4.3. Atomic Fine Structure lines

4.3.1. Atomic Carbon: [C I]

In a recent study,

Walter et al. (2011)

summarize the [C I] observations of 13

high–redshift galaxies (this compilation included work by

Barvainis et al. 1997,

Weiß et al. 2003,

2005a,

Pety et al. 2004,

Wagg et al. 2006,

Ao et al. 2005,

Riechers et al. 2009a,

Casey et al. 2009,

Lestrade et al. 2010,

Danielson et al. 2011).

These systems studied in [C I] are amongst the

brightest emitters both in the submillimeter regime and in CO line

emission, and many of them are lensed. The main finding was that the [C

I] properties of

high–redshift systems do not differ significantly to what is found in

low–redshift systems, including the Milky Way. In addition, there are

no major differences in [C I] properties between the

QSO– and SMG–selected samples. The

L′CI(1−0) /

L′CO ratios (0.29 ± 0.12) are similar to

low–z galaxies (e.g., 0.2 ± 0.2,

Gerin & Phillips

2000).

As argued in Sec. 2.8, measurements of

both [C I] lines can

constrain gas excitation temperatures of the molecular gas,

independent of radiative transfer modeling. For the available sample,

a carbon excitation temperature of 29.1 ± 6.3 K was derived

(Walter et al. 2009).

This temperature is lower than what is typically found

in starforming regions in the local universe despite the fact that the

sample galaxies have star formation rate surface densities on kpc

scales of 100's of M⊙ yr−1

kpc−2. However, the

temperatures are roughly consistent with published dust temperatures

of high–redshift starforming galaxies

(Beelen et al. 2006,

Kovács et al.,

2006,

2010,

Harris et al. 2012).

Low carbon excitation as well as low

dust temperatures could indicate that the measurements include a

significant amount of gas/dust unaffected by star formation.

The [C I] abundances in the current high–z

galaxy sample of (X[[C I]] / X[H2] =

(8.4 ± 3.5) × 10−5) are comparable,

within the uncertainties, to what is found in local starforming

environments

(Walter et al. 2009).

The [C I] lines are a negligible

coolant (average LCI / LFIR = (7.7

± 4.6) × 10−6).

There is tentative evidence that this ratio may be elevated in the

SMGs by a factor of a few compared to the QSOs

(Walter et al. 2009).

4.3.2. Ionized Carbon: [C II]

The [C II] 158µm line is rapidly

becoming a work–horse line for the study of the cool atomic gas

in distant galaxies. The number of [C II] detections

at high redshift has increased substantially in the

last few years using the CSO, PdBI, APEX and the SMA

(Maiolino et al. 2009;

Stacey et al. 2010;

Iono et al. 2006b,

Hailey–Dunsheath et

al. 2010,

Wagg et al. 2010;

Walter et al. 2012;

Cox et al. 2011;

De Breuck et al. 2011;

Gallerani et al. 2012),

as well as a few detections in strongly lensed galaxies with Herschel

(Ivison et al. 2010b,

Valtchanov et al. 2011).

To date, there have been about two

dozen [C II] detections from galaxies at z

> 1, including a number at

z > 6 (see Sec. 5.2). ALMA

during early science has already demonstrated the ability to detect

[CII] emission from relatively normal star forming galaxies at high

redshift (LBGs, LAEs) in [C II] emission

(Wagg et al. 2012;

Carilli et al. 2012;

Riechers et al. 2013).

Fig. 6 shows a broad scatter in the

[C II] / FIR ratio at

z > 1. Note that the high–z galaxy sample all have FIR

luminosities ≥ 1012 L⊙. However,

there is a trend for luminous AGN to have

the lowest ratios, and star–formation dominated galaxies

(eg. SMGs) to have ratios closer to that of the Milky Way (e.g.,

Stacey et al. 2010).

Stacey et al. (2010)

use the CO, FIR, and [C II] emission to argue

that the [C II] emission is dominated by PDRs in the

star forming galaxies. From these observations, they derive the physical

conditions in the PDRs in high redshift galaxies, finding gas densities

of order a few × 104 cm−3, and the

strength of the FUV radiation field: G ∼ 103

× 1.6 × 10−3 erg cm−2

s−1, where 1.6 × 10−3 erg

cm−2 s−1 is the local Galactic

interstellar radiation field (ISRF, ‘Habing field'). They find a

further factor 10 higher G for the AGN dominated systems. Their

modeling also implies that the scale of the PDRs is ≥ few kpc,

much larger than for GMCs or nuclear starburst galaxies at low

redshift. The fraction of molecular gas mass associated with PDRs is

between 20% and 100% in their sample.

Swinbank et al. (2012)

detect likely [CII] 158µm emission in two

SMGs using ALMA, from which they derive redshifts of z ∼

4.4 and 4.2. They suggest that the bright-end of the [CII] luminosity

function increases dramatically with redshift, with close to a thousand-fold

increase in the number density of galaxies with L[[CII]

> 109 L⊙ from z = 0 to 4. We

discuss [CII] detections in a number

of z > 6 galaxies in Sec. 5.2.

4.3.3. Other fine structure lines

There have been only a few detections of fine structure lines other

than [C II] at high redshift to date, mostly in

strongly lensed systems using principally the PdBI and Herschel. We

summarize some of the physical diagnostics that have been achieved with

such observations.

In their Herschel study of SMGs at z ∼ 1.4,

Coppin et al. (2012)

find that the [O I] 63 µm / FIR ratio is

comparable to spiral galaxies nearby, and much higher than what is seen

in low–z nuclear starbursts. Similar results were found by

Ferkinhoff et al. (2010)

and

Sturm et al. (2010)

in their [O I] 63µm,

[O III] 52µm, and

[C II] 158µm study of a strongly lensed

ULIRG at z = 1.3 (see also

Hailey–Dunsheath et

al. 2010).

The interesting conclusion is

that, although these systems are intrinsically ULIRG or HyLIRGs, they

do not show a deficit in the major PDR cooling lines as seen in nearby

ULIRGs. A similar conclusion has been reached based on

[C II] and [N II]

observations of lensed SMGs

(Nagao et al. 2012;

De Breuck et al. 2011).

In particular, the compilation of

Decarli et al. (2012)

shows a mean value for [N II] 122µm /

FIR ∼ 3 × 10−4, close to

that seen in low z disk galaxies, although admittedly the scatter is

large.

Conversely,

Valtchanov et al. (2011)

and

Ferkinhoff et al. (2010;

2011)

perform PDR analyses of lensed SMGs at z ∼ 3, using FIR,

CO, [O III] [N II] and/or

[C II] measurements. They find mean densities

of order 2000 cm−3, FUV radiation field of G =

200, and sizes for the emitting region ∼ 0.6 kpc. The

relatively strong [O III]

implies that the radiation field must be very hot (35,000K), either

dominated by O9.5 stars or an AGN NLR–like radiation field.

The [C II] 158µm line is

realizing its potential in

the study of the cooler atomic gas in distant galaxies. This strong

line will be a workhorse–line for redshift determinations in the

first galaxies, and in the study of galaxy dynamics at the highest

redshifts. However, the interpretation of [C II]

emission is not straighforward, since [C II] traces

both the neutral as well as the

ionized medium, and it appears to be suppressed in high–density

regions. Likewise, multi–fine structure line diagnostics at high

redshift have tremendous potential to probe the physical conditions in

the ISM in high z galaxies, but studies are in their infancy. The

current observations reflect the heterogeneous nature of SMGs, with

many showing spiral galaxy–like FSL properties, and a few showing

evidence for an AGN–like component.

4.4. Dense gas tracers and other molecules at high

redshift

Emission from high dipole molecules, such as HCN and HCO+, comes

only from highest density regions in molecular clouds

(ncr > 104

cm−3), corresponding to regions directly associated

with active star formation. These lines are typically an

order of magnitude weaker than the integrated CO emission from star

forming galaxies, although the higher dense gas fraction in nuclear

starbursts can lead to line strengths up to 25% of CO

(Riechers et al. 2011c).

To date, there remain just a handful of detections at

high redshift, mostly from strongly lensed hyper–starbursts

(Riechers et al. 2006b,

2010c;

2011c;

García-Burillo et

al. 2006,

Danielson et al. 2011).

The two strongly lensed hyper-starburst/AGN, APM 0827+5255 at z =

3.91 and the Cloverleaf quasar (H1413+117;

Barvainis et al. 1994)

at z = 2.56 play an analogous role to the Galactic molecular

cloud SgrB2, as high–z ‘molecule factories'. These are the

only sources with multiple

transitions detected from molecules and isotopes other than 12CO,

including HCN, HNC, HCO+, H2O, CN,

13CO. We briefly review the recent results on these sources.

For APM 0827+5255, strong emission from very high order

transitions is seen

(Weiß et al. 2007a;

Riechers et al. 2010c).

Formally, the critical densities for excitation for the higher order HCN and

HCO+ transitions are > 108

cm−3. The excitation suggests

emission from a region with a radius ∼ 200 pc around the AGN,

where IR pumping (Sec. 4.4) plays a dominant role in

molecular excitation. The J = 6 isomer ratio of HNC/HCN = 0.5 is

consistent with the IR pumping model

(Riechers et al. 2010c).

For the Cloverleaf quasar, low and high order emission from

HCN and HCO+, and CN have been detected

(Solomon et al. 2003;

Riechers 2006b,

2007a,

2011c;

Barvainis et al. 1997;

Wilner et al. 1995).

Modeling including the multiple CO transitions implies

collisional excitation by gas with a mean kinetic temperature of 50 K

and density of 104.8 cm−3, in a molecular

region with a radius ∼ 0.8 kpc

(Riechers et al. 2011c).

Hence, in contrast to

APM 0827+5255, the Cloverleaf is consistent with collisional

excitation in a hyperstarburst region with a radius of order 1 kpc.

The only detection of rare isotopic emission at high redshift is

13CO 3–2 emission from the Cloverleaf

(Henkel et al. 2010).

The isotopic luminosity ratio for the J = 3 emission is 40, eight times

larger than that seen in Milky Way GMCs. The only nearby galaxy with a

ratio approaching that of the Cloverleaf is the merging ULIRG NGC 6240,

where

Greve et al. (2009)

obtain a lower limit of 30.

Henkel et al. (2010)

conclude that the large isotope ratio in the Cloverleaf

likely reflects a real 13C abundance deficit, by a factor of

four or so relative to Milky Way GMC value of 40 to 90

(Henkel et al. 1993).

Progress has recently been made on detecting thermal emission from

(rest frame) FIR ro–vibrational transitions of water at high redshift

(van der Werf et

al. (2011),

Omont et al. 2011;

Combes et al. 2012a).

In APM 0827+5255, van der Werf et al. show that

the lower level

transitions (rest frame frequencies below 1 THz) likely arise in

collisionally excited gas with kinetic temperatures of 100 K, and

clump densities of order 3 × 106

cm−3. The higher order

transitions require radiative excitation by IR radiation on a scale of

a few hundred parsecs around the AGN, with conditions similar to the

nuclear regions of the low redshift starburst/AGN galaxy, Mrk 231

(van der Werf et

al. 2010).

They argue for distributed gas heating, as expected for a

star–formation heated PDR, and not an AGN dominated XDR.

We note that a linear relation between

L′HCN(1−0) and LFIR has been found

for local galaxies , including spirals and ULIRGs

(Gao & Solomon

2004a,

2004b),

unlike the non-linear relationship between

L′CO(1−0) and LFIR. It has been

shown that this relation extends even to the dense cores of galactic

clouds

(Wu et al. 2005).

One interpretation of this finding is that

the dense molecular phase traced by HCN is immediately preceeding the

onset of star formation. However,

Riechers et al. (2007b)

have shown

that this linear relationship appears to break down in the

high–redshift systems studied to date, i.e. that they have lower HCN

luminosities than expected based on a linear extrapolation from the

low–redshift (and Galactic) measurements. This finding may indicate

even higher average gas densities in the highest–redshift systems

compared to dense environments found locally. It may also hint at an

increased star formation efficiency (or both,

Riechers et al. 2007b).

Progress on dense gas tracers at high redshift has been

limited to strongly lensed, extremely luminous systems, due to the

limited sensitivity of existing telescopes. The results thus far

indicate a mixture of PDR/XDR heating and collisional excitation in

compact extreme starburst regions. Given the very high average

densities in dense starbursts at high redshift, cosmic ray heating and

related modeling will play an increasingly important role. In the

future, much progress is expected from much broader bandwidths, as

they will in almost all cases yield ‘involuntary line surveys' of

dense gas tracers.

4.5. Star formation laws and gas consumption

Quantifying the relationship between star formation rate (SFR) and gas

density (the so–called ‘star formation law',

‘Schmidt law', ‘Schmidt–Kennicutt law' or

‘K–S law') has been a key goal in

observational astrophysics over the last 50 years, starting with

Schmidt (1959).

Any relationship between SFR and gas surface

densities has important implications for our understanding of galaxy

formation and evolution as it describes how efficiently galaxies turn

their gas into stars. Such a ‘law' would also serve as essential

input to hydrodynamical simulations (and other models) of galaxy evolution

that start with dark matter halos that are beeing fed by gas

infall. It should be noted that the term ‘law' (in a sense of a

physical law) is not appropriate to describe an empirical

relationship. However, we stick to this nomenclature as it is now

common practice to refer to the SFR–gas relationship. This

relationship has been reviewed recently for nearby galaxies by

Kennicutt & Evans

(2012).

Herein we focus on z > 1 galaxies.

The relation between star formation rate and gas density is typically

expressed in terms of surface densities

(ΣSFR ∼ Σgasn). One

complication is that the measurement of surface densities requires

resolved measurements of galaxies. In the compilation by

Kennicutt (1998a,

1998b)

the integrated star formation rates and gas masses were averaged over

entire galaxy disks to derive an average surface density for a given

galaxy. Observational capabilities have improved since, and spatially

resolved measurements of the star formation rate and gas surface

densities are now available for a number of nearby galaxies (e.g.,

Kennicutt et al. 2007,

Bigiel et al. 2008,

2011,

Leroy et al. 2008,

2013,

Rahman et al. 2011,

2012,

Liu et al. 2011).

These spatially resolved measurements typically have resolutions of one

kiloparsec or slightly better, i.e. they still average over many

individual giant molecular clouds that are typically ∼ 50 pc in

size. It is clear from Galactic studies that the relationship

ΣSFR ∼ Σgasn must

break down on very small scales: e.g. a star forming region will ionize

its immediate surrounding, thus destroying any relationship that may be

present on larger scale. This has been quantified by

Schruba et al. (2010)

and

Onodera et al. (2010)

who have shown that in the case of M 33 the star

formation law on large/galactic scales breaks down on scales below

∼ 300 pc. There is now largely consensus that the star formation

law is ‘molecular', i.e. that the equation above becomes:

ΣSFR ∼

ΣH2n. H I

does not appear to be intimitly

linked to the star formation process through such a simple

description, even though it is clear that H I is

needed to form H2 to begin with

(Kennicutt & Evans

2012).

Measuring the star formation law at high redshift is significantly

complicated by the fact that few resolved CO measurements exist, and

dust and/or AGN emission confuses determination of optical sizes. The

recent comprehensive study of

Tacconi et al. (2013)

shows that, where both the size of the SF disk as well as the size of

the CO emission could be measured, reasonable agreement between the

quantities was found (see also

Daddi et al. 2010a).

However, typically only global measurements of SFR and molecular gas are

plotted in high redshift research.

Unlike in the local universe, where L′CO luminosities

and H2 masses can be calculated from the CO(1–0) or

CO(2–1) transitions

(Sec. 2.5), the majority of

high–redshift measurements are done using higher J

transitions. To put all high–redshift systems on the same plot,

the L′CO luminosity of the CO(1–0) transition

needs to be estimated, assuming the typical excitiation of the galaxy

under consideration.

Narayanan et al. (2010a)

discusses how the slope

of the star formation law could change if different transitions of CO are

used and if the different line ratios are not accounted for

properly. We consider the excitation ladder in Sec. 4.1,

and in the analysis below, we adopt a set of canonical values for

different galaxy types, based on the (admittedly limited) available

data (Tab. 2).

Two further complications are involved when comparing derived

quantities, such as gas mass and star formation rate. First is CO

luminosity to gas mass conversion factor, α. As discussed in

detail in Sec. 4.2, different source populations likely

have different values of α. And second is derivation of the SFR

from observed SEDs. Methods include: SED fitting of UV/optical/IR data

for CSGs, FIR luminosities for SMGs and AGN after correction for hot

dust heated by the AGN

(Jiang et al. 2010,

Leipski et al. 2010,

2013,

Riechers 2011,

Genzel et al. 2010),

and radio luminosities assuming the radio–FIR correlation

(Condon 1992).

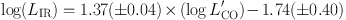

To avoid the above complications, we focus on the empirical

relationship between the observables, LFIR and

L′CO(1−0), for all high–redshift

galaxies detected to date in

Figure 9. Most of the galaxies detected at high

redshift have luminosities (both FIR and CO) that are much higher than

typical systems seen in the local universe (grey/black data

points). At the highest luminosities, the SMGs and quasar host

galaxies dominate. The entire distribution can be fit with a power law

of the form

with a slope that is consistent with the power law found

when looking at the intergrated properties of nearby galaxies only

(including ULIRGs,

Kennicutt 1998a).

However, it is also apparent that

the CSGs have higher CO luminisities for a given LFIR (or

SFR) compared to the QSO/SMG population

(Daddi et al. 2008;

2010;

Tacconi et al. 2010;

2013).

Genzel et al. (2010)

and

Daddi et al. (2010b)

argue that there are in fact 2 sequences visible in this plot,

one ‘starburst' sequence (red dashed line) and one ‘main

sequence'/CSG relation (grey dashed line). For the latter,

Daddi et al. (2010b)

and

Genzel et al. (2010)

derived:

with L′CO in units of K km s−1

pc2, LIR in units of L⊙. The

values given here are from

Daddi (2010b),

but the relation derived by

Genzel et al. (2010)

is very similar.

Both

Genzel et al. (2010)

and

Daddi et al. (2010b)

proceed to calculate molecular gas masses from the CO luminosities using a

molecular gas conversion factors α that is about five times

higher in the case of the CSGs relative to SMGs, based on the

arguments in Sec. 4.2. This then leads to an increased

gap between the CSG population and the SMGs/QSOs with an offset of

roughly 1 dex in LFIR. This strengthens the presence of two

different star formation regimes, one highly–efficient star formation

mode for starburst (presumably triggered by mergers and/or other

interactions) and one less–efficient and thus

longer–lasting mode for the CSGs (‘main–sequence'

galaxies).

The different star formation efficiencies, defined as SFE =

LFIR / L′CO (in units of

L⊙ / (K km s−1)

pc2)−1, are further highlighted in the

right panel of Fig. 9.

It is immediately obvious from this plot that the SFE of the CSG is

lower compared to the high–redshift quasars and SMGs by a factor of

few, and that the CSGs reach values that are similar to what is found

in local galaxies. The offset between the two sequences becomes

even more pronounced when different α conversion factors are

used for the two high–redshift galaxy populations.

The gas consumption timescale is defined simply as: τc =

Mgas / SFR, i.e. the time it would take to use up the

available molecular gas reservoir given the current star formation rate. The

right hand of axis of Fig. 9 shows these timescales,

assuming the two different conversion factors relevant to SMGs and

CSGs (Sec. 4.2). The gas consumption timescale in CSGs

is of order 108 to 109 years

(Daddi et al. 2008,

2010a,

b,

Genzel et al. 2010,

Tacconi et al. 2010,

2013),

comparable to that in low redshift disk galaxies

(Bolatto et al. 2013).

For comparison, the SMGs and other HyLIRGs galaxies have extremely short

consumption timescales ≤ 107 yr.

In the local universe it has been shown by

Kennicutt (1998a,

b)

that if the dynamical timescale is taken into account

(i.e. ΣSFR is plotted as a function of

Σgas / τdyn and not only as a

function of Σgas), all galaxies fit on one relation with

slope ∼ 1. Both

Genzel et al. 2010

and

Daddi et al. 2010

showed that this trend also continues at high–redshift, i.e. that a

‘universal' star formation law is obtained, with no separation

between the two star forming sequences. The dynamical timescale

τdyn

is here defined to be the rotational period at the last measured point

in a galaxy (typically taken to be the half–light radius). We note

that the latter is not easily determined given current observations at

high redshift, and that a physical interpretation of this finding is

not straightforward. In a sense it is puzzling that the global

properties of a galaxy (τdyn) appear to be related to local

star formation process.

Krumholz et al. (2011)

perform a similar analysis, only using an estimate of the local gas

free–fall time, and conclude that all systems, from local

molecular clouds to distant galaxies (starburst and

main–sequence), fall on a single star formation law in which the

star formation rate is simply ∼ 1% of the

molecular gas mass per local free–fall time.

As a general comment, it should be kept in mind that there are

significant selection effects that may contribute to the apparent

functional behavior in the ‘SF law' plot. For example, as essentially

all galaxies have been pre–selected based on their star formation

activity, it is conceivable that large molecular gas reservoirs exist

at low LFIR; they have simply not yet been looked at.

Constraining the ‘star formation law', i.e. relating the

star formation rate to the available gas reservoir, has been the focus

of many studies at low and high redshift in the past decade. Even

though it is not a ‘law' in a physical sense, this empirical relation

has the potential power to predict one quantity from the other, sheds

light on the star formation process, and serves as vital input in

numerical simulations and galaxy formation models. At high redshift

there is a clear relation between the main observables,

log(LIR) and log(L′CO). Once

translated into physical quantities (SFR and

H2 mass) there is now good evidence for two sequences of star

formation, one ‘starburst' sequence, with very short consumption

times, 107 – 108 yr (local ULIRGs, SMGs and

QSOs) and a ‘normal, quiescent' sequence, ∼

109 yr (local spirals, CSG, ‘main sequence' galaxies).

4.6. Imaging of the molecular gas in early galaxies

The last few years has seen tremendous progress in high resolution

imaging of the molecular gas in high redshift galaxies, mainly by the

VLA and the IRAM PdBI. Imaging of CO emission has been performed on

the brighter sources with a spatial resolution comparable to that of

the HST ( ∼ 0.15"), or rougly 1 kpc at z > 1. Following we

highlight a few of the best examples to date (see

Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Best examples of resolved

molecular line emission at high redshift from which gas kinematics can be

derived. These are (from left to right): The CSG EGS 13035123

(Tacconi et al. 2010),

the QSO BRI 1335

(Riechers et al. 2008b)

and the SMG GN 20

(Hodge et al. 2012).

The top row shows the integrated

CO(2–1) maps of the targets. The bottom row shows the velocity

fields of the targets; here the color indicates the velocity at which

gas is moving a given position on the sky. The velocity scale ranges

from (blue to red): –65 to +100 km s−1,

–154 to +154 km s−1, –300

to 300 km s−1, respectively. The beamsizes are given

in the bottom left of each galaxy; the bar indicates 1" on the sky

(size in kpc is also given at the respective redshift).

4.6.1. A typical CSG

In their ground breaking studies of CSG,

Tacconi et al. (2010)

and

Daddi et al (2010a)

find gas rich disks without extreme starbursts (see also

Tacconi et al. 2012;

Sec. 3.5). The best imaging

study to date of a CSG is that of the CO(3–2) emission from

EGS 13035123 using the PdBI at 0.6" resolution by

Tacconi et al. (2010)

(Fig. 7). The H2 mass is 1.3 ×

1011 (α / 3.2) M⊙, distributed in a

rotating disk with a radius of 8 kpc, and a terminal rotation velocity

of 200 km s−1. While clearly rotating, the disk also

has a high internal velocity dispersion ≥ 20 km

s−1, implying substantial disk turbulence.

The disk is punctuated by high brightness temperature clumps with

radii ≤ 2 kpc and masses ∼ 5 × 109

M⊙. The gas surface densities are ∼ 500

M⊙ pc−2, a factor few

larger than for Galactic GMCs, and they hypothesize that these clumps

are conglomerates of a number of Galactic–type GMCs rather than a

single giant GMC, due to the relatively low internal velocity

dispersions ( ∼ 20 km s−1)

Daddi et al. (2010a)

obtain similar imaging results for a few CSG at z ∼ 1.5,

although at somewhat lower spatial resolution.

These imaging observations of CO in z ∼ 1 to 3 CSG have been

critical to the interpretation that the CSG are gas–dominated,

rotating disk galaxies undergoing steady, high levels of star

formation (see Sec. 3.5). They also

helped to constrain the conversion factor α for these systems

through dynamical arguments (Sec. 4.2).

4.6.2. BRI 1335-0417: tidally disturbed gas

surrounding a luminous quasar

BRI 1335-0417 at z = 4.4 was among the first

optically selected, very high–z quasars to be identified with a

hyper–luminous FIR host galaxy, implying an accreting SMBH with

mass ∼ 109 M⊙

coeval with an extreme starburst (SFR ∼ 1000

M⊙ yr−1)

(Guilloteau et

al. 1997).

The host galaxy has been detected in CO line emission, with an implied

M(H2) ∼ 8 ×

1010(α / 0.8) M⊙

(Carilli et al. 2002a),

as well as strong [C II] emission

(Wagg et al. 2010).

BRI 1335-0417 is a broad absorption line quasar,

indicating AGN outflow. Fig. 7 (middle) shows

the CO images from the of BRI 1335-0417 from the VLA

(Riechers et al. 2008b).

These are the highest quality CO images of any non–lensed

high–z quasar to date. The system shows complex morphology in the

gas on a scale of ∼ 1″. The molecular gas shows multiple

components distributed over ∼ 7 kpc, with a pronounced tail

extending to the north, peaking in a major CO clump ∼

0.7″ from the quasar, and with a few other streams connecting to

the quasar from other directions. While there is an overall

north–south velocity gradient, the general velocity field appears

chaotic.

Riechers et al. interpret the complex gas structure in

BRI 1335-0417 as tidal remnants from a

late–stage, gas–rich (‘wet') merger. The merger

drives gas accretion onto the main galaxy, fueling the

hyper–starburst and the luminous AGN, generally consistent with

the high molecular excitation seen in quasar hosts (Sec. 4.1). For comparison, the SMG–quasar pair

BRI 1202-0725 at z ∼ 4.7

shows a distinct SMG and quasar, possibly corresponding to an

early–stage merger, before galaxy coalesence

(Salome et al. 2012,

Carilli et al. 2012).

4.6.3. GN 20: an SMG with a gas rich disk

The galaxy GN 20 is the brightest SMG in the GOODS–North

field

(Pope et al. 2006),

and the host galaxy is heavily obscured at optical wavelengths.

Daddi et al. (2009a)

made a serendipitous redshift

determination of z = 4.05 from CO emission using the PdBI (by

targeting a nearby CSG). Two other SMGs at this redshift have been

detected in CO and dust continuum emission about 20" to the west

(Carilli et al. 2011;

Hodge et al. 2012),

and there is a clear

over–density of galaxies in this field, with 15 LBGs with

zphot ∼ 4 within a radius or 25" of GN 20

(Daddi et al. 2009).

A long observation using the JVLA in early science of the CO (2–1)

emission

(Hodge et al. 2012)

shows that the CO is distributed in a

disk with a diameter ∼ 14 kpc (Fig. 7,

right). The regions emitting in CO and dust continuum are mostly

obscured in the HST I–band image. The only tracable optical

emission is seen at the edges of the source

(Hodge et al. 2012).

Such heavy obscuration in the optical is characteristic of SMGs.

The GN 20 disk dynamics are consistent with a standard

‘tilted–ring'

gas rotation model, with a dynamical mass of 5.4 ± 2.4 1011

M⊙. Observations at 1kpc resolution reveal that 30% to

50% of the gas is in giant clumps with gas masses of a few ×

109 (α / 0.8) M⊙, brightness

temperatures between 16 K and 31

K, and line widths of order 100 km s−1

(Hodge et al. 2012).

A dynamical analysis suggests the clumps could be

self–gravitating. The gas surface densities of the clumps are

∼ 4000 (α / 0.8) M⊙

pc−2, more than an order of magnitude larger than

typical GMCs. An analysis of the overall galaxy dynamics has been used

to determine the value of α in GN 20 (see Sec. 4.2).

The apparent disk in GN 20 suggests that not all HyLIRGs at very high

redshift result from an ongoing major merger. This

conclusion has also been reached for a few other SMGs at lower

redshift, where low order CO observations show large, disk–like gas

reservoirs similar to GN 20

(Ivison et al. 2011;

Riechers et al. 2011;

Greve et al. 2004,

Ivison et al. 2010a,

b).

In GN 20, the clumpy disk is consistent with that

expected in the cold mode accretion model (e.g.

Kereš et al. 2005,

Dekel et al. 2006,

2009),

only now scaled up by almost an order of magnitude in FIR

luminosity relative to typical CSG

(Sec. 5.1.2). It is

possible that the star formation in this gas rich disk has been

enhanced due to gravitational harrasment by the other SMGs and smaller

galaxies in the proto–cluster.

Spatially resolving the molecular gas emission in high

redshift galaxies is to date restricted to very few, bright, sources.

Imaging the molecular and cool atomic gas a few selected high redshift

galaxies has revealed 10 kpc–scale, clumpy and turbulent, but

apparently rotating disks in CSG and some SMGs, as well as strongly

tidally disturbed gas distributions in some SMGs and quasar hosts.

Theoretical models without negative feedback (negative feedback =

ejection of material due to either star formation or AGN activity)

predict both a higher gas content in massive galaxies in the nearby

Universe, and a larger population of star forming massive galaxies

today, than observed. At high galactic masses, including AGN feedback

mitigate these problems in simulations, both driving gas out of the

immediate ISM of the host galaxy via AGN winds, and suppressing

further gas accretion from the IGM via large–scale radio jets

(Fabian 2012).

Direct evidence for feedback has been seen in nearby galaxies,

including outflows seen in OH far–IR lines, molecular emission lines,

optical lines, and atomic fine structure lines (e.g., in the case of

M 82:

Strickland & Heckman

2009,

Walter et al. 2002,

Martin 1998).

The fact that old, gas–poor massive galaxies have now been

seen at redshifts of 2 and beyond suggest that feedback must be an

important process even earlier.

Recent observations have detected evidence for feedback on kpc–scales

in very early galaxies. One of the best examples of AGN feed–back

are the broad line wings of the [C II] emission from

the z = 6.4 quasar J1148+5251 by

Maiolino et al. (2012).

They derive an outflow

velocities of 1300 km s−1, an outflow rate of

Other systems show varying degrees of feedback in the cooler gas. The

BRI 1202-0725 quasar–SMG galaxy pair does

show evidence for a broad wing in the quasar host galaxy

[C II] 158µm spectrum, but the

outflow kinetic energy is well below that of J1148+5251, and star

formation likely dominates gas depletion in the galaxy

(Wagg et al. 2012;

Carilli et al. 2012).

Weiß et al. (2012)

detect a 250 km s−1 outflow in a z = 2.8 quasar

in both CO and [C I]. They derive a lower limit to

the mass outflow rate of 180 M⊙

yr−1, which is slightly larger than the star formation

rate in the host galaxy.

Molecular Outflows have only very recently been detected in a

few high–redshift systems. Given that they feature (by

definition) broad and faint line wings they remained undetected by

past observations, both due to missing sensitivity and insufficient

bandwidth. Quantifying the kinetic energy and masses associated with

such outflows will provide important input in galaxy simulations in

which feedback by stellar (or AGN) activity is a key driver for galaxy

evolution.

1 Including a correction for the relative

contribution of the CMB increases these values by about 35% at z =

2.5

(Ivison et al. 2011).

Back.

source

SMG

QSO

CSG

MW

M 82

L′CO(2−1) /

L′CO(1−0)

0.85

0.99

0.97

0.5

0.98

L′CO(3−2) /

L′CO(1−0)

0.66

0.97

0.56

0.27

0.93

L′CO(4−3) /

L′CO(1−0)

0.46

0.87

0.2

0.17

0.85

L′CO(5−4) /

L′CO(1−0)

0.39

0.69

–

0.08

0.75

outfl

∼ 3500 M⊙

yr−1, and kinetic power of: PK

∼ 1.9 × 1045 erg s−1. This

is roughly 0.6% of the quasar bolometric luminosity, well below the

theoretical upper limit to a radiatively driven quasar outflow of 5% of

the bolometric luminosity

(Lapi et al. 2005),

but it is barely consistent with the maximum kinetic power that can be

driven by the associated starburst in the quasar host

(Veilleux et al. 2005).

Likewise, theoretical models indicate that star formation driven winds

reach a maximum velocity of ∼ 600 km s−1

(Thacker et al. 2006).

Maiolino et al. (2012)

argue that the outflow is most likely AGN–driven. The gas

consumption timescale for the outflow is comparable to that due to

star formation, of order 107 yr.

outfl

∼ 3500 M⊙

yr−1, and kinetic power of: PK

∼ 1.9 × 1045 erg s−1. This

is roughly 0.6% of the quasar bolometric luminosity, well below the

theoretical upper limit to a radiatively driven quasar outflow of 5% of

the bolometric luminosity

(Lapi et al. 2005),

but it is barely consistent with the maximum kinetic power that can be

driven by the associated starburst in the quasar host

(Veilleux et al. 2005).

Likewise, theoretical models indicate that star formation driven winds

reach a maximum velocity of ∼ 600 km s−1

(Thacker et al. 2006).

Maiolino et al. (2012)

argue that the outflow is most likely AGN–driven. The gas

consumption timescale for the outflow is comparable to that due to

star formation, of order 107 yr.