3.1. The effect of a magnetic field on the neutron-proton conversion rate

The reactions which are responsible for the chemical equilibrium of neutrons and protons in the early Universe are the weak processes

| (3.2) |

| (3.3) |

| (3.4) |

In the absence of the magnetic field and in the presence of a heat-bath, the rate of each of the previous processes takes the generic form

| (3.5) |

where pi is the four momentum, Ei is

the energy and

fi is the distribution function of the i-th

particle species involved in the equilibrium processes. All processes

(3.2, 3.3, 3.4) share the same amplitude

determined by the

standard electroweak theory.

determined by the

standard electroweak theory.

The total neutrons to protons conversion rate is

| (3.6) |

where q and  are respectively the

neutron-proton mass difference and the electron, or positron,

energy, both expressed in units of the electron mass me.

We neglect here the

electron and neutrino electron chemical potentials as these are

supposed to be small quantities during BBN

[46].

The rate 1 /

are respectively the

neutron-proton mass difference and the electron, or positron,

energy, both expressed in units of the electron mass me.

We neglect here the

electron and neutrino electron chemical potentials as these are

supposed to be small quantities during BBN

[46].

The rate 1 /  is defined by

is defined by

| (3.7) |

where G is the Fermi constant and

gA /

gV

gA /

gV  -

1.262. For T

-

1.262. For T

0 the

integral in Eq. (3.6) reduces to

0 the

integral in Eq. (3.6) reduces to

| (3.8) |

and  n =

n =

/ I is the neutron

time-life.

/ I is the neutron

time-life.

The total rate for the inverse processes (p

n) can be

obtained reversing the sign of q in Eq. (3.6). It is

assumed here that the neutrino chemical potential is vanishing

(at the end of Sec. 3.4 it will also be

discussed the case where

such an assumption is relaxed). Since, at the BBN time temperature is much

lower than the nucleon masses, neutrons and protons are assumed to be at

rest.

n) can be

obtained reversing the sign of q in Eq. (3.6). It is

assumed here that the neutrino chemical potential is vanishing

(at the end of Sec. 3.4 it will also be

discussed the case where

such an assumption is relaxed). Since, at the BBN time temperature is much

lower than the nucleon masses, neutrons and protons are assumed to be at

rest.

As pointed out by Matese and O'Connell [86, 88], the main effect of a magnetic field stronger than the critical value Bc on the weak processes (3.2-3.4) comes-in through the effect of the field on the electron, and positron, wave function which becomes periodic in the plane orthogonal to the field [38]. As a consequence, the components of the electron momentum in that plane are discretized and the electron energy takes the form

| (3.9) |

where we assumed B to be directed along the z axis. In the above, n denotes the Landau level, and s= ± 1 if, respectively, the electron spin is along or opposed to the field direction. Besides the effect on the electron dispersion relation, the discretization of the electron momentum due to the magnetic field has also a crucial effect on the phase-space volume occupied by these particles. Indeed, in the presence of a field with strength larger than Bc the substitution

| (3.10) |

has to be performed [91]. Since we only consider here magnetic fields which are much weaker than the proton critical value (eB << mp2), we can safely disregard any effect related to the periodicity of the proton wave function.

The squared matrix element for each of the reactions (3.2-3.4) is the same when the spin of the initial nucleon is averaged and the spins of the remaining particles are summed. Neglecting neutron polarization, which is very small for B < 1017 G, we have [86]

| (3.11) |

It is interesting to observe the singular behaviour when a new Landau level opens up (En = pz). Such an effect is smoothed-out when temperature is increased [92].

Expressions (3.9) and (3.10) can be used to

determined the rate of the processes (3.2-3.4)

in a heat-bath and in the presence of an over-critical magnetic field. We

start considering the neutron

-decay. One finds

-decay. One finds

| (3.12) |

where

B /

Bc and nmax

is the maximum Landau level accessible to the final state electron

determined by the requirement pz(n)2

= q2 - me2 - 2n

eB > 0 . It is noticeable that for

B /

Bc and nmax

is the maximum Landau level accessible to the final state electron

determined by the requirement pz(n)2

= q2 - me2 - 2n

eB > 0 . It is noticeable that for

> 1/2

(q2 -1)2 = 2.7 only the n = 0 term

survives in the sum. As a consequence the

> 1/2

(q2 -1)2 = 2.7 only the n = 0 term

survives in the sum. As a consequence the

-decay rate

increases linearly with

-decay rate

increases linearly with

above such

a value. The computation leading to

(3.12) can be readily generalized to determine the

rate of the reactions (3.2) and (3.3) for

above such

a value. The computation leading to

(3.12) can be readily generalized to determine the

rate of the reactions (3.2) and (3.3) for

0

0

| (3.13) |

and

| (3.14) |

By using the well know expression of the Euler-MacLaurin sum (see

e.g. Ref. [91])

it is possible to show that in the limit B

0

Eqs. (3.12-3.14) reduces to the standard

expressions derived in the absence of the magnetic field

(8)

0

Eqs. (3.12-3.14) reduces to the standard

expressions derived in the absence of the magnetic field

(8)

The global neutron to proton conversion rate is obtained by summing the last three equations

| (3.15) |

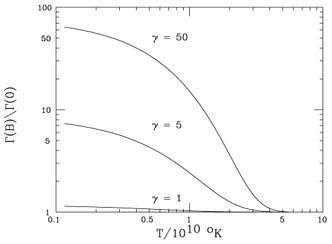

It is noticeable that the contribution of Eq. (3.12) to

the total rate (3.15) is canceled by the second term of

(3.14). As a consequence it follows that

Eq. (3.15) does not depend on nmax and the n

p

conversion grows linearly with the field strength above

Bc. From Fig. 3.1 the reader

can observe that, in the

range considered for the field strength, the neutron depletion rate

drops quickly to the free-field when the temperature grows above

few MeV's. Such a behaviour is due to the suppression of the

relative population of the lowest Landau level when eB >>

T2.

p

conversion grows linearly with the field strength above

Bc. From Fig. 3.1 the reader

can observe that, in the

range considered for the field strength, the neutron depletion rate

drops quickly to the free-field when the temperature grows above

few MeV's. Such a behaviour is due to the suppression of the

relative population of the lowest Landau level when eB >>

T2.

|

Figure 3.1. The neutron-depletion rate

|

In the absence of other effects, the consequence of the

amplification of

n

n

p

due to the magnetic field would be to decrease the relic abundance of

4He. In fact, a larger

p

due to the magnetic field would be to decrease the relic abundance of

4He. In fact, a larger

n

n

p

implies a lower value

of the temperature (TF) at which the neutron to proton

equilibrium ratio is frozen because of the expansion of the

Universe. It is evident from (3.1) that the final value of

(n/p) drops exponentially as TF is

increased. Furthermore,

once n / p has been frozen, occasional neutron

p

implies a lower value

of the temperature (TF) at which the neutron to proton

equilibrium ratio is frozen because of the expansion of the

Universe. It is evident from (3.1) that the final value of

(n/p) drops exponentially as TF is

increased. Furthermore,

once n / p has been frozen, occasional neutron

-decays can

still reduce the relic neutron abundance

[46]. As it

follows from Eq. (3.12), the presence of a strong magnetic field

accelerates the process which may give rise to a further

suppression of the n/p ratio. In practice, however, neutron

decay takes place at a times when the magnetic field strength has already

decreased significantly due to the Universe expansion so that the

effect is negligible.

-decays can

still reduce the relic neutron abundance

[46]. As it

follows from Eq. (3.12), the presence of a strong magnetic field

accelerates the process which may give rise to a further

suppression of the n/p ratio. In practice, however, neutron

decay takes place at a times when the magnetic field strength has already

decreased significantly due to the Universe expansion so that the

effect is negligible.

The result of Matese and O'Connell has been confirmed by Cheng et al. [93] and by Grasso and Rubinstein [94]. Among other effects, the authors of Ref. [94] considered also QED and QCD corrections in the presence of strong magnetic fields. In principle these corrections may not be negligible in the presence of over-critical magnetic fields and their computation requires a proper treatment. In order to give to the reader a feeling of the relevance of this issue, we remind him the wrong result which was derived by O'Connell [39] by neglecting QED radiative correction to the electron Dirac equation in the presence of a strong magnetic field. By assuming the electron anomalous magnetic moment to be independent on the external field O'Connell found

| (3.16) |

For B > (4 /

/

)

Bc this expression give rise to negative

values of the ground state energy which, according to O'Connell,

is the manifestation of the instability of the vacuum to spontaneous

production of electron-positron pairs. This conclusion, however, is in

contradiction with standard electrodynamics from which we know

that a constant magnetic field cannot transfer energy. This problem was

solved by several authors (see e.g. Ref.

[37]) by

showing that by properly accounting for QED radiative corrections

to the Dirac equation no negative value of the electron energy

appear. The effect can be parametrized by a field dependent

correction to the electron mass, me

)

Bc this expression give rise to negative

values of the ground state energy which, according to O'Connell,

is the manifestation of the instability of the vacuum to spontaneous

production of electron-positron pairs. This conclusion, however, is in

contradiction with standard electrodynamics from which we know

that a constant magnetic field cannot transfer energy. This problem was

solved by several authors (see e.g. Ref.

[37]) by

showing that by properly accounting for QED radiative corrections

to the Dirac equation no negative value of the electron energy

appear. The effect can be parametrized by a field dependent

correction to the electron mass, me

me + M, where

me + M, where

| (3.17) |

Such a correction was included in Refs.

[94,

95].

It is interesting to observe that although pair production cannot

occur at the expense of the magnetic field, this phenomenon can take

place in

a situation of thermodynamic equilibrium where pair production can

be viewed as a chemical reaction e+ +

e- <->

, the

magnetic field playing the role of a catalysts agent

[96].

We will return on this issue in

Sec. 3.3.

, the

magnetic field playing the role of a catalysts agent

[96].

We will return on this issue in

Sec. 3.3.

Even more interesting are the corrections due to QCD. In fact, Bander and Rubinstein showed that in the presence of very strong magnetic fields the neutron-proton effective mass difference q becomes [97] (for a more detailed discussion of this issue see Chap. 5)

| (3.18) |

The function f(B) gives the rate of mass change due to

colour forces being affected by the field. µN is

the nucleon magnetic

moment. For nucleons the main change is produced by the chiral

condensate growth, which because of the different quark content of

protons and neutrons makes the proton mass to grow

faster [97].

Although, as a matter of principle, the

correction to Q should be accounted in the computation of the

rates that we reported above, in practice however, the effect on

the final result is always negligible. More subtle it is

the effect of the correction to Q on the neutron-to-proton

equilibrium ratio. In fact, as it is evident from Eq. (3.1),

in this case the correction to Q enters exponentially to

determine the final neutron-to-proton ratio. However, the actual

computation performed by Grasso and Rubinstein

[94]

showed that the effect on the light element abundances is

sub-dominant whenever the field strength is smaller than

1018

Gauss.

1018

Gauss.