8.6. Internal Shocks

Internal shocks are the leading mechanism for energy conversion and production of the observed gamma-ray radiation. We discuss, in this section, the energy conversion process, the typical radiation frequency and its efficiency.

8.6.1. Parameters for Internal Shocks

Internal shocks take place when an inner shell overtakes a slower

outer shell. Consider a fast inner shell with a Lorentz factor

r

that collides with a slower shell whose Lorentz factor is

r

that collides with a slower shell whose Lorentz factor is

s.

If

s.

If

r

r

s

~

s

~  then the

inner shell will overtake the outer one at:

then the

inner shell will overtake the outer one at:

|

(73) |

where  is the initial

separation between the shells in the observer's rest frame and

10 =

is the initial

separation between the shells in the observer's rest frame and

10 =  / 1010

cm and

/ 1010

cm and

100

=

100

=  /

100. Clearly internal shocks are relevant only if

they appear before the external shock that is produced as the

shell sweeps up the ISM. We show in

section 8.7.1 that the

necessary condition for internal shocks to occur before the external

shock is:

/

100. Clearly internal shocks are relevant only if

they appear before the external shock that is produced as the

shell sweeps up the ISM. We show in

section 8.7.1 that the

necessary condition for internal shocks to occur before the external

shock is:

|

(74) |

where  and

and

are two

dimensionless parameters.

The parameter,

are two

dimensionless parameters.

The parameter,  ,

characterizes the interaction of the flow

with the external medium and it is defined in Eq. 92

(see section 8.7.1).

The second parameter,

,

characterizes the interaction of the flow

with the external medium and it is defined in Eq. 92

(see section 8.7.1).

The second parameter,

, characterizes

the variability of the flow:

, characterizes

the variability of the flow:

|

(75) |

We have seen in section 7.4 that for

internal shocks the duration of the burst

T

/ c and the

duration of individual spikes

/ c and the

duration of individual spikes

T

T

/ c. The

observed ratio

/ c. The

observed ratio  defined in

section 2.2 must equal 1 /

defined in

section 2.2 must equal 1 /

and this sets

and this sets

0.01.

0.01.

The overall duration of a burst produced by internal shocks

equals  /

c. Thus, whereas external shocks

require an extremely large value of

/

c. Thus, whereas external shocks

require an extremely large value of

to produce

a very short burst, internal shocks can produce a short burst with

a modest value of the Lorentz factor

to produce

a very short burst, internal shocks can produce a short burst with

a modest value of the Lorentz factor

. This

eases somewhat the baryon purity constraints on

source models. The condition 74 can be turned into a condition that

. This

eases somewhat the baryon purity constraints on

source models. The condition 74 can be turned into a condition that

is

sufficiently small:

is

sufficiently small:

|

(76) |

where we have used

T =  /

c and we have defined T10 = T / 10 s and

/

c and we have defined T10 = T / 10 s and

0.01 =

0.01 =

/ 0.01. It

follows that internal shocks take place in relatively "low"

/ 0.01. It

follows that internal shocks take place in relatively "low"

regime.

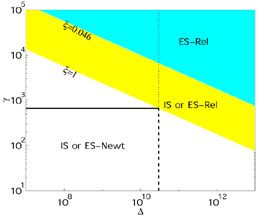

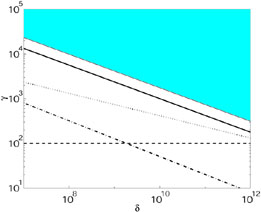

Fig. 23

depicts the regimes in the physical parameter space

(

regime.

Fig. 23

depicts the regimes in the physical parameter space

( ,

,

)

in which various shocks are possible. It also depicts an example of

a T =

)

in which various shocks are possible. It also depicts an example of

a T =  /

c = 1s line.

/

c = 1s line.

|

Figure 23. Different scenarios in the

|

Too low a value of the Lorentz factor leads to a large optical depth in

the internal shocks region. Using Eq. 27 for Re, at

which the optical depth for Compton scattering of the photons on the

shell's electrons equals one, Eq. 73 for

R and the condition

Re

and the condition

Re  R

R we find:

we find:

|

(77) |

In addition, the radius of emission should be large enough so that the

optical depth for

e+

e- will be less than

unity (

e+

e- will be less than

unity (

<

1). There are several ways to consider

this constraint. The strongest constraint is obtained if one demands

that the optical depth of an observed high energy, e.g. 100MeV photon

will be less than unity

[210,

211].

Following these calculations and using Eq. 73 to express

R

<

1). There are several ways to consider

this constraint. The strongest constraint is obtained if one demands

that the optical depth of an observed high energy, e.g. 100MeV photon

will be less than unity

[210,

211].

Following these calculations and using Eq. 73 to express

R we find:

we find:

|

(78) |

This constraint, which is due to the

interaction, is

generally more important than the constraint due to Compton scattering:

that is

interaction, is

generally more important than the constraint due to Compton scattering:

that is

>

>

e.

e.

Eq. 76, and the more restrictive Eq. 78

constrains  to a relatively narrow range:

to a relatively narrow range:

|

(79) |

This can be translated to a rather narrow range of emission radii:

|

(80) |

In Fig. 24, we plot the allowed regions in the

and

and  parameter space.

Using the less restrictive

parameter space.

Using the less restrictive

e limit 77 we find:

e limit 77 we find:

|

Three main conclusions emerge from the discussion so far. First, if

the spectrum of the observed photons extends beyond 100 MeV (as was the

case in the bursts detected by EGRET

[83])

and if those high energy photons are emitted in the same region as the

low energy ones then the condition on the pair production,

,

Eq. 78 is stronger than the condition on Compton

scattering Eq. 81. This increases the required

Lorentz factors. Second, the Compton scattering limit (which is

independent of the observed high energy tail of the spectrum) poses

also a lower limit on

,

Eq. 78 is stronger than the condition on Compton

scattering Eq. 81. This increases the required

Lorentz factors. Second, the Compton scattering limit (which is

independent of the observed high energy tail of the spectrum) poses

also a lower limit on

. However,

this is usually less restrictive then the

. However,

this is usually less restrictive then the

limit. Finally, one sees in

Fig. 24 that optically thin internal shocks are

produced only in a narrow region in the

(

limit. Finally, one sees in

Fig. 24 that optically thin internal shocks are

produced only in a narrow region in the

( ,

,

)

plane. The region is quite small if the stronger pair production limit

holds. In this case there is no single value of

)

plane. The region is quite small if the stronger pair production limit

holds. In this case there is no single value of

that can

produce peaks over the

whole range of observed durations. The allowed region is larger if we

use the weaker limits on the opacity. But even with this limit there

is no single value of

that can

produce peaks over the

whole range of observed durations. The allowed region is larger if we

use the weaker limits on the opacity. But even with this limit there

is no single value of

that

produces peaks with all

durations. The IS scenario suggests that bursts with very narrow peaks

should not have very high energy tails and that very short bursts may

have a softer spectrum.

that

produces peaks with all

durations. The IS scenario suggests that bursts with very narrow peaks

should not have very high energy tails and that very short bursts may

have a softer spectrum.

|

Figure 24. Allowed regions for internal

shocks in the

|

8.6.2. Physical Conditions and Emission from Internal Shocks

Provided that the different parts of the shell have comparable Lorentz

factors differing by factor of ~ 2, the internal shocks are mildly

relativistic. The protons' thermal Lorentz factor will be of order of

unity, and the shocked regions will still move highly relativistically

towards the observer with approximately the initial Lorentz factor

. In front

of the shocks the particle density of the shell is

given by the total number of baryons

E /

. In front

of the shocks the particle density of the shell is

given by the total number of baryons

E /  mp c2 divided by the

co-moving volume of the shell at the radius

R

mp c2 divided by the

co-moving volume of the shell at the radius

R which is 4

which is 4 R

R 2

2

. The

particle density behind the shock is higher

by a factor of 7 which is the limiting compression possible by

Newtonian shocks (assuming an adiabatic index of relativistic gas,

i.e., 4/3). We estimate the pre-shock density of the

particles in the shells as: [E /

(

. The

particle density behind the shock is higher

by a factor of 7 which is the limiting compression possible by

Newtonian shocks (assuming an adiabatic index of relativistic gas,

i.e., 4/3). We estimate the pre-shock density of the

particles in the shells as: [E /

( mp c2)] /

(4

mp c2)] /

(4 (

(

2)2

2)2

). We introduce

). We introduce

int

as the Lorentz factor of the internal

shock. As this shock is relativistic (but not extremely relativistic)

int

as the Lorentz factor of the internal

shock. As this shock is relativistic (but not extremely relativistic)

int

is of order of a few. Using Eq. 48

for the particle density n and the thermal energy density

e behind the shocks we find:

int

is of order of a few. Using Eq. 48

for the particle density n and the thermal energy density

e behind the shocks we find:

|

(81) |

|

(82) |

We have defined here

12 =

12 =

/ 1012

cm. Using Eq. 49 we find:

/ 1012

cm. Using Eq. 49 we find:

|

(83) |

Using Eqs. 49, 51, 56 and 81 we can estimate the typical synchrotron frequency from an internal shock. This is the synchrotron frequency of an electron with a "typical" Lorentz factor:

|

(84) |

The corresponding observed synchrotron cooling time is:

|

(85) |

Using Eq. 53 we can express

e,min in terms of

e,min in terms of

int

to estimate the minimal synchrotron frequency:

int

to estimate the minimal synchrotron frequency:

|

(86) |

The energy emitted by a "typical electron" is around 220keV. The

energy emitted by a "minimal energy" electron is about one order of

magnitude lower than the typical observed energy of ~ 100 keV. This

should correspond to the break energy of the spectrum.

This result seems in a good agreement with the observations. But this

estimate might be misleading as both

B and

B and

e

might be significantly lower than unity. Still these values of (h

e

might be significantly lower than unity. Still these values of (h

syn)obs

are remarkably close to the observations. One might

hope that this might explain the observed lower cutoff of the GRB

spectrum. Note that a lower value of

syn)obs

are remarkably close to the observations. One might

hope that this might explain the observed lower cutoff of the GRB

spectrum. Note that a lower value of

B or

B or

e might be

compensated by a higher value of

e might be

compensated by a higher value of

int.

This is advantageous as shocks with higher

int.

This is advantageous as shocks with higher

int

are more efficient (see section 8.6.4).

int

are more efficient (see section 8.6.4).

The synchrotron cooling time at a given frequency (in the observer's frame) is given by:

|

(87) |

We recover the general trend

tsyn  (h

(h  )-1/2 of

synchrotron emission. However if (as we expect quite generally)

this cooling time is much

shorter than Tang it does not determine the

width of the observed peaks. It will correspond to the observed

time scales if, for example,

)-1/2 of

synchrotron emission. However if (as we expect quite generally)

this cooling time is much

shorter than Tang it does not determine the

width of the observed peaks. It will correspond to the observed

time scales if, for example,

B is

small. But then the

"typical" photon energy will be far below the observed range.

Therefore, it is not clear this relation can explain the observed

dependence of the width of the bursts on the observed energy.

B is

small. But then the

"typical" photon energy will be far below the observed range.

Therefore, it is not clear this relation can explain the observed

dependence of the width of the bursts on the observed energy.

8.6.3. Inverse Compton in Internal Shocks

The calculations of section 8.4 suggest that

the typical

Inverse Compton (IC) (actually synchrotron - self Compton) radiation

from internal shocks will be at energy higher by a factor

e2

then the typical synchrotron frequency. Since synchrotron emission is

in the keV range and

e2

then the typical synchrotron frequency. Since synchrotron emission is

in the keV range and  e,min

e,min

mp

/ me, the expected IC

emission should be in the GeV or even TeV range. This radiation might

contribute to the prompt very high energy emission that accompanies

some of the GRBs

[83].

mp

/ me, the expected IC

emission should be in the GeV or even TeV range. This radiation might

contribute to the prompt very high energy emission that accompanies

some of the GRBs

[83].

However, if the magnetic field is extremely low:

B ~

10-12 then we would expect the IC photons to be in the

observed ~ 100 keV region:

B ~

10-12 then we would expect the IC photons to be in the

observed ~ 100 keV region:

|

(88) |

Using Eqs. 71 and 83 we find that the cooling time for synchrotron-self Compton in this case is:

|

(89) |

This is marginal. It is too large for some bursts and possibly adequate for others. It could possibly be adjusted by a proper choice of the parameters. It is more likely that if Inverse Compton is important then it contributes to the very high (GeV or even TeV) signal that accompanies the lower energy GRB (see also [250]).

8.6.4. Efficiency in Internal Shocks

The elementary unit in the internal shock model (see section 7.4) is a a binary (two shells) encounter between a rapid shell (denoted by the subscript r) that catches up a slower one (denoted s). The two shells merge to form a single shell (denoted m). The system behaves like an inelastic collision between two masses mr and ms.

The efficiency of a single collision between two shells was calculated

earlier in section 8.1.1. For multiple

collisions the efficiency

depends on the nature of the random distribution. It is highest if the

energy is distributed equally among the different shells. This can be

explained analytically. Consider a situation in which the mass of the

shell, mi is correlated with the (random) Lorentz factor,

i

as mi

i

as mi

i

i . Let all the shells collide and merge

and only then emit the thermal energy as radiation. Using conservation

of energy and momentum we can calculate the overall efficiency:

. Let all the shells collide and merge

and only then emit the thermal energy as radiation. Using conservation

of energy and momentum we can calculate the overall efficiency:

|

(90) |

Averaging over the random variables

i,

and assuming a large number of shells

N

i,

and assuming a large number of shells

N

we obtain:

we obtain:

|

(91) |

This formula explains qualitatively the numerical results: the

efficiency is maximal when the energy is distributed equally among

the different shells (which corresponds to

= - 1).

= - 1).

In a realistic situation we expect that the internal energy will be

emitted after each collision, and not after all the shells have

merged. In this case there is no simple analytical formula. However,

numerical calculations show that the efficiency of this process is low

(less than 2%) if the initial spread in

is only a

factor of two

[32].

However the efficiency could be much higher

[33].

The most efficient case is when the shells have a

comparable energy but very different Lorentz factors. In this case

(

is only a

factor of two

[32].

However the efficiency could be much higher

[33].

The most efficient case is when the shells have a

comparable energy but very different Lorentz factors. In this case

( = - 1, and

spread of Lorentz factor

= - 1, and

spread of Lorentz factor  max /

max /

min > 103) the efficiency is as

high as 40%. For a moderate spread of Lorentz factor

min > 103) the efficiency is as

high as 40%. For a moderate spread of Lorentz factor

max /

max /  min = 10, with

min = 10, with  = - 1, the

efficiency is 20%.

= - 1, the

efficiency is 20%.

The efficiency discussed so far is the efficiency of conversion of kinetic energy to internal energy. One should multiply this by the radiative efficiency, discussed in 8.5 (Eq. 72) to obtain the overall efficiency of the process. The resulting values may be rather small and this indicates that some sort of beaming may be required in most GRB models in order not to come up with an unreasonable energy requirement.

8.6.5. Summary - Internal Shocks

Internal shocks provide the best way to explain the observed temporal structure in GRBs. These shocks, that take place at distances of ~ 1015 cm from the center, convert two to twenty percent of the kinetic energy of the flow to thermal energy. Under reasonable conditions the typical synchrotron frequency of the relativistic electrons in the internal shocks is around 100 keV, more or less in the observed region.

Internal shocks require a variable flow. The situation in which an inner shell is faster than an outer shell is unstable [251]. The instability develops before the shocks form and it may affect the energy conversion process. The full implications of this instability are not understood yet.

Internal shocks can extract at most half of the shell's energy [32, 33, 69]. Highly relativistic flow with a kinetic energy and a Lorentz factor comparable to the original one remains after the internal shocks. Sari & Piran [20] pointed out that if the shell is surrounded by ISM and collisionless shock occurs the relativistic shell will dissipate by "external shocks" as well. This predicts an additional smooth burst, with a comparable or possibly greater energy. This is most probably the source of the observed "afterglow" seen in some counterparts to GRBs which we discuss later. This leads to the Internal-External scenario [252, 20, 26] in which the GRB itself is produced by an Internal shock, while the "afterglow" that was observed to follows some GRBs is produced by an external shock.

The main concern with the internal shock model is its low efficiency

of conversion of kinetic energy to

-rays. This

could be of order

twenty percent under favorable conditions and significantly lower

otherwise. If we assume that the "inner engine" is powered by a

gravitational binding energy of a compact object (see

section 10.1) a low efficiency may

require beaming to overcome an overall energy crisis.

-rays. This

could be of order

twenty percent under favorable conditions and significantly lower

otherwise. If we assume that the "inner engine" is powered by a

gravitational binding energy of a compact object (see

section 10.1) a low efficiency may

require beaming to overcome an overall energy crisis.